![]()

PART ONE

Blue Ocean Strategy

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Creating Blue Oceans

A ONETIME ACCORDION PLAYER, stilt walker, and fire eater, Guy Laliberté is now CEO of Cirque du Soleil, one of Canada’s largest cultural exports. Cirque’s productions to date have been seen by some 150 million people in over three hundred cities around the world. In less than twenty years since its creation, Cirque du Soleil achieved a level of revenues that took Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey—the once global champion of the circus industry—more than one hundred years to attain.

What makes this growth all the more remarkable is that it was not achieved in an attractive industry but rather in a declining industry in which traditional strategic analysis pointed to limited potential for growth. Supplier power on the part of star performers was strong. So was buyer power. Alternative forms of entertainment—ranging from various kinds of urban live entertainment to sporting events to home entertainment—cast an increasingly long shadow. Children cried out for video games rather than a visit to the traveling circus. Partially as a result, the industry was suffering from steadily decreasing audiences and, in turn, declining revenue and profits. There was also increasing sentiment against the use of animals in circuses by animal rights groups. Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey had long set the standard, and competing smaller circuses essentially followed with scaled-down versions. From the perspective of competition-based strategy, then, the circus industry appeared unattractive.

Another compelling aspect of Cirque du Soleil’s success is that it did not win by taking customers from the already shrinking circus industry, which historically catered to children. Cirque du Soleil did not compete with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey. Instead it created uncontested new market space that made the competition irrelevant. It appealed to a whole new group of customers: adults and corporate clients prepared to pay a price several times as great as traditional circuses for an unprecedented entertainment experience. Significantly, one of the first Cirque productions was titled “We Reinvent the Circus.”

New Market Space

Cirque du Soleil succeeded because it realized that to win in the future, companies must stop competing with each other. The only way to beat the competition is to stop trying to beat the competition.

To understand what Cirque du Soleil achieved, imagine a market universe composed of two sorts of oceans: red oceans and blue oceans. Red oceans represent all the industries in existence today. This is the known market space. Blue oceans denote all the industries not in existence today. This is the unknown market space.

In the red oceans, industry boundaries are defined and accepted, and the competitive rules of the game are known.1 Here, companies try to outperform their rivals to grab a greater share of existing demand. As the market space gets crowded, prospects for profits and growth are reduced. Products become commodities, and cutthroat competition turns the red ocean bloody.

Blue oceans, in contrast, are defined by untapped market space, demand creation, and the opportunity for highly profitable growth. Although some blue oceans are created well beyond existing industry boundaries, most are created from within red oceans by expanding existing industry boundaries, as Cirque du Soleil did. In blue oceans, competition is irrelevant because the rules of the game are waiting to be set.

It will always be important to swim successfully in the red ocean by outcompeting rivals. Red oceans will always matter and will always be a fact of business life. But with supply exceeding demand in more industries, competing for a share of contracting markets, while necessary, will not be sufficient to sustain high performance.2 Companies need to go beyond competing. To seize new profit and growth opportunities, they also need to create blue oceans.

Unfortunately, blue oceans are largely uncharted. The dominant focus of strategy work over the past thirty years has been on competition-based red ocean strategies.3 The result has been a fairly good understanding of how to compete skillfully in red waters, from analyzing the underlying economic structure of an existing industry, to choosing a strategic position of low cost or differentiation or focus, to benchmarking the competition. Some discussions around blue oceans exist.4 However, there is little practical guidance on how to create them. Without analytic frameworks to create blue oceans and principles to effectively manage risk, creating blue oceans has remained wishful thinking that is seen as too risky for managers to pursue as strategy. This book provides practical frameworks and analytics for the systematic pursuit and capture of blue oceans.

The Continuing Creation of Blue Oceans

Although the term blue oceans is new, their existence is not. They are a feature of business life, past and present. Look back 120 years and ask yourself, How many of today’s industries were then unknown? The answer: many industries as basic as automobiles, music recording, aviation, petrochemicals, health care, and management consulting were unheard of or had just begun to emerge at that time. Now turn the clock back only forty years. Again, a plethora of multibillion-and trillion-dollar industries jumps out—e-commerce; cell phones; laptops, routers, switches, and networking devices; gas-fired electricity plants; biotechnology; discount retail; express package delivery; minivans; snowboards; and coffee bars to name a few. Just four decades ago, none of these industries existed in a meaningful way.

Now put the clock forward twenty years—or perhaps fifty years—and ask yourself how many now unknown industries will likely exist then. If history is any predictor of the future, again the answer is many of them.

The reality is that industries never stand still. They continuously evolve. Operations improve, markets expand, and players come and go. History teaches us that we have a hugely underestimated capacity to create new industries and re-create existing ones. In fact, the more than half-century-old Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) system published by the US Census was replaced in 1997 by the North America Industry Classification Standard (NAICS) system. The new system expanded the ten SIC industry sectors into twenty sectors to reflect the emerging realities of new industry territories.5 The services sector under the old system, for example, is now expanded into seven business sectors ranging from information to health care and social assistance.6 Given that these systems are designed for standardization and continuity, such a replacement shows how significant the expansion of blue oceans has been.

Yet the overriding focus of strategic thinking has been on competition-based red ocean strategies. Part of the explanation for this is that corporate strategy is heavily influenced by its roots in military strategy. The very language of strategy is deeply imbued with military references—chief executive “officers” in “headquarters,” “troops” on the “front lines.” Described this way, strategy is about confronting an opponent and fighting over a given piece of land that is both limited and constant.7 Unlike war, however, the history of industry shows us that the market universe has never been constant; rather, blue oceans have continuously been created over time. To focus on the red ocean is therefore to accept the key constraining factors of war—limited terrain and the need to beat an enemy to succeed—and to deny the distinctive strength of the business world: the capacity to create new market space that is uncontested.

The Impact of Creating Blue Oceans

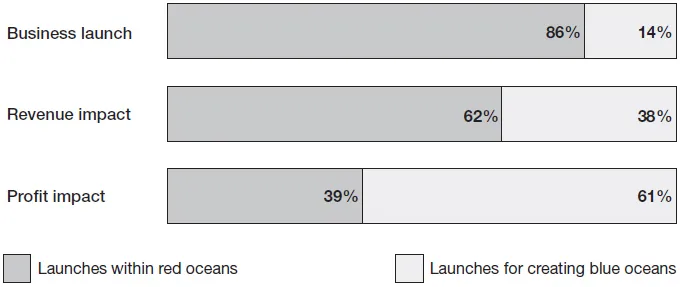

We set out to quantify the impact of creating blue oceans on a company’s growth in both revenues and profits in a study of the business launches of 108 companies (see figure 1-1). We found that 86 percent of the launches were line extensions, that is, incremental improvements within the red ocean of existing market space. Yet they accounted for only 62 percent of total revenues and a mere 39 percent of total profits. The remaining 14 percent of the launches were aimed at creating blue oceans. They generated 38 percent of total revenues and 61 percent of total profits. Given that business launches included the total investments made for creating red and blue oceans (regardless of their subsequent revenue and profit consequences, including failures), the performance benefits of creating blue waters are evident. Although we don’t have data on the hit rate of success of red and blue ocean initiatives, the global performance differences between them are marked.

FIGURE 1-1

The profit and growth consequences of creating blue oceans

The Rising Imperative of Creating Blue Oceans

There are several driving forces behind a rising imperative to create blue oceans. Accelerated technological advances have substantially improved industrial productivity and have allowed suppliers to produce an unprecedented array of products and services. The result is that in increasing numbers of industries, supply exceeds demand.8 The trend toward globalization compounds the situation. As trade barriers between nations and regions are dismantled and as information on products and prices becomes instantly and globally available, niche markets and havens for monopoly continue to disappear.9 While supply is on the rise as global competition intensifies, there is no clear evidence of an increase in demand relative to supply, and statistics even point to declining populations in many developed markets.10

The result has been accelerated commoditization of products and services, increasing price wars, and shrinking profit margins. Industrywide studies on major American brands confirm this trend.11 They reveal that for major product and service categories, brands are generally becoming more similar, and as they are becoming more similar, people increasingly select based on price.12 People no longer insist, as in the past, that their laundry detergent be Tide. Nor will they necessarily stick to Colgate when Crest is on sale, and vice versa. In overcrowded industries, differentiating brands becomes harder in both economic upturns and downturns.

All this suggests that the business environment in which most strategy and management approaches of the twentieth century evolved is increasingly disappearing. As red oceans become increasingly bloody, management will need to be more concerned with blue oceans than the current cohort of managers is accustomed to.

From Company and Industry to Strategic Move

How can a company break out of the red ocean of bloody competition? How can it create a blue ocean? Is there a systematic approach to achieve this and thereby sustain high performance?

In search of an answer, our initial step was to define the basic unit of analysis for our research. To understand the roots of high performance, the business literature typically uses the company as the basic unit of analysis. People have marveled at how companies attain strong, profitable growth with a distinguished set of strategic, operational, and organizational characteristics. Our question, however, was this: Are there lasting “excellent” or “visionary” companies that continuously outperform the market and repeatedly create blue oceans?

Consider, for example, In Search of Excellence and Built to Last.13 The bestselling book In Search of Excellence was published some thirty years ago. Yet within two years of its publication, a number of the companies surveyed began to slip into oblivion: Atari, Chesebrough-Pond’s, Data General, Fluor, National Semiconductor. As documented in Managing on the Edge, two-thirds of the identified model firms in the book had fallen from their perches as industry leaders within five years of its publication.14

The book Built to Last continued in the same footsteps. It sought out the “successful habits of visionary companies” that had a long-running track record of superior performance. To avoid the pitfalls of In Search of Excellence, however, the survey period of Built to Last was expanded to the entire life span of the companies, while its analysis was limited to firms more than forty years old. Built to Last also became a bestseller.

But again, upon closer examination, deficiencies in some of the visionary companies spotlighted in Built to Last have come to light. As illustrated in the book Creative Destruction, much of the success attributed to some of the model companies in Built to Last was the result of industry-sector performance rather than the companies themselves.15 For example, Hewlett-Packard (HP) met the criteria of Built to Last by outperforming the market over the long term. In reality, while HP outperformed the market, so did the entire computer-hardware industry. What’s more, HP did not even outperform the competition within the industry. Through this and other examples, Creative Destruction questioned whether “visionary” companies that continuously outperform the market have ever existed.

If there is no perpetually high-performing company and if the same company can be brilliant at one moment and wrongheaded at another, it appears that the company is not the appropriate unit of analysis in exploring the roots of high performance and blue oceans.

As discussed earlier, history also shows that industries are constantly being created and expanded over time and that industry conditions and boundaries are not given; individual actors can shape them. Companies need not compete head-on in a given industry space; Cirque du Soleil created a new market space in the entertainment sector, generating strong, profitable growth as a result. It appears, then, that neither the company nor the industry is the best unit of analysis in studying the roots of profitable growth.

Consistent with this observation, our study shows that the str...