![]()

Part 1

Paradigms, Policies & Processes

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Early Years of Nation-Building: Reflections on Singapore’s Urban History

Alan F. C. Choe

Introduction

Singapore has one of the most striking and ever-evolving skylines in the world, created through a process of rapid urban development (Figure 1). In the short span of 50 years, the city-state has transformed from a third world to a modern global city. Today, Singapore ranks as one of the top 10 most livable cities in the world. Singapore’s success in urban development and infrastructure efficiency has also elevated the nation’s position as a desirable country for economic development, coupled with sound economic policies and a stable political environment, thus spurring greater urbanisation and development.

This transformation from a “fishing village” to a modern world-class metropolitan city was beyond the imaginations of many, given, some 50 years ago, slums and squatter settlements were rampant. Lack of modern sanitation in tandem with poor public health and safety standards were then the norm. Today, we often take for granted the privileges of health, safety, and modern conveniences that include an accessible and operational mass rapid transit (MRT) system at our fingertips. It is therefore useful to reflect where we came from and the progress Singapore has made in a post-independence era. Today’s Singapore, particularly our model of urbanisation, is the envy of many countries.

This chapter is an attempt at reflecting the history of Singapore’s early years, when extremely poor living conditions were part and parcel of the everyday urban experience. Improving such dire living conditions involved intense struggles and passionate efforts towards modernisation and urbanisation. The strategies, methods, and improvisations for urban development needed to compensate for the lack of readily available resources and information on the subject as televisions, publications, and the Internet were non-existent then. By shedding light on our trials and tribulations, it is hoped that the experiences of my generation will offer some useful and thought-provoking considerations for future successive generations.

Figure 1. Singapore’s modern urban skyline featuring Marina Bay and the Central Business District.

Source: Urban Redevelopment Authority.

In this chapter, I would like to explore how urban planning was introduced to Singapore during the colonial era and why urban renewal was incorporated into the nation-building process following Singapore’s independence. This moment of urban change was led by the clear vision and determination of fearless political leaders and government officials. Through cooperation, innovation and courage, a city was developed and a nation built in two generations. In order to value the fruits of this labour we must start at the beginning.

The Colonial Legacy: An Urban Story of Inheritance and Loss

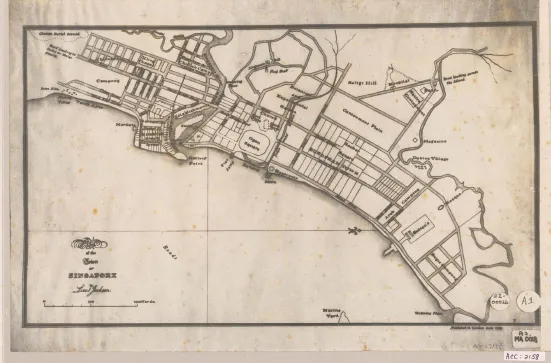

The story of Singapore’s urban history traditionally begins with the arrival of Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819 and the strategic establishment of the island into a colonial entrepôt serving the Straits Settlements trade route. During this 140-year colonial reign, the British rulers sought to imprint their Eurocentric urban planning principles on the physical terrain of Singapore. Under the colonial administration, Singapore inherited a development strategy that favoured a system of planning to promote economic development and bolster development growth. Thus, Singapore’s earliest detailed town plan (1822) (Figure 2), prepared through a Town Planning Committee formed by Sir Stamford Raffles and led by Lieutenant Philip Jackson, served as the blueprint for the spatial organisation of the future town of Singapore.

The “Plan of the Town of Singapore”, as the planning document was called, set forth three proposals for the layout of the new settlement sited at the gateway of the Singapore River. Firstly, a gridiron street pattern was imposed on the land as a means of inculcating a rational sense of uniformity and orderliness. Land was then subsequently divided into narrow lots which private individuals could purchase on a freehold basis or on a leasehold term of up to 999 years, as was the liberal policy then towards land ownership and tenure. Construction at the time consisted mainly of low-rise shop-house-style buildings of one- to two-storeys with commerce permitted on the ground floor to support the expanding mercantile activities along the Singapore River. Secondly, land was assigned functional specialisation with areas carved out for administrative, educational, recreational, and religious activities. This initial zoning of land led to the provision of infrastructure and amenities such as civic institutions, schools, and parks for use by the growing numbers of Europeans settling in Singapore. These places, however, ostracised the local inhabitants. Thirdly, and in relation to the local populace, the town plan concentrated and segregated the various racial and ethnic groups into designated residential enclaves. Some enclaves, such as Chinatown, were further divided according to clan dialects with the Hokkien, Teochew, and Cantonese communities occupying various parts of the Chinese district.

Figure 2. Plan of the Town of Singapore, 1822.

Source: Survey Department Collection, Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The ethnic enclaves created social and spatial divisions; at the same time, they attracted newly-arrived migrants who naturally gravitated to areas that resembled the familiarities and kinship of their homelands. These migrant settlements soon became more and more populated as demand for labour coincided with Singapore’s growth from a fledgling trading outpost to a major commercial seaport. In the early days of development, a massive influx of foreign capital and enterprising immigrants entered Singapore, thereby contributing further to the acceleration of economic growth and transforming a once sleepy town into a bustling city. During this growth period, Singapore inherited from the colonial predecessors a modern system of planning which laid the foundations for urban development. The colonial legacy also included the inheritance of a physical morphology characterised by its fine-grained compact urban fabric and a human-scaled streetscape consisting of low-rise shophouse architecture.

A century later, the urban scene in Singapore became a stark contrast of its early days. By the 1920s, the city core (Central Area) was experiencing severe issues of residential overcrowding, poor sanitation, and street congestion. Many European settlers were relocating from the Central Area to the outlying urban fringe, where larger estate homes could be built in more open space settings. This transition led to the gradual blurring of boundaries and overlapping of functional zones within the Central Area, as earlier settlement patterns conformed less and less to the intentions of the 1822 town plan. In 1927, the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) was formed by the British colonial administration to help with progressive environmental improvements such as the introduction of backlanes—for service maintenance and collection of refuse—between shophouses that once existed back-to-back. The SIT was later granted greater authority to build low-cost public housing, the first being the Tiong Bahru Estate in the 1930s. However, the SIT did not produce sufficient numbers of units to mitigate the rising need for adequate housing made more acute following the Pacific War (1941–45). Urban conditions in the Central Area dramatically worsened.

The shophouse, which was designed to accommodate a single household, was partitioned into smaller living quarters which, in many cases, were further subdivided into cubicles and sublet by tenants or the landlord. This practice of absorbing multiple families in shophouses, many of which had been indiscriminately altered with extensions and additions, resulted in severe overcrowding. These densities ranged from 1,200 to 1,700 people per hectare with occasional instances of densities on some blocks reaching approximately 2,500 people per hectare (Chua, 1989). The overcrowding situation severely aggravated the health and safety of those living in the dilapidated shophouses. Ironically, the Rent Control Act of 1947, which sought to protect tenants from exorbitant rental increases arising from the acute shortage of housing following the Pacific War, contributed to the physical deterioration of buildings as landlords were no longer incentivised to maintain and upkeep their properties. Elsewhere, slums and squatter settlements were proliferating in open spaces where salvaged materials such as attap leaves, corrugated iron sheets, and wooden planks were used in the construction of makeshift dwellings and ancillary spaces for unregulated businesses. These unauthorised developments posed tremendous risks to the inhabitants and the surrounding environment, especially when activities involving the use of fire, such as cooking, could not be properly contained and controlled.

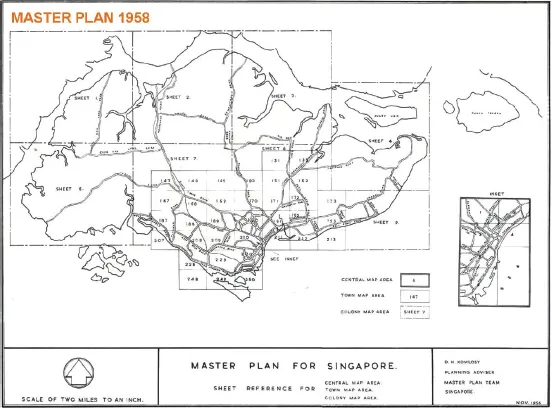

It became increasingly obvious to the colonial government that Singapore’s urban situation would spiral into a vicious cycle unless an intervention was made to regulate growth and development. This intervention was introduced in the form of the Singapore Improvement Ordinance (1952), which required the SIT to convene a work team that would carry out a detailed island-wide survey to help guide future development. The study was conducted over a period of three years, after which the team produced a Preliminary Island Plan (1955). This draft plan, which was conceptualised by colonial officers at the time, was based mainly on British town-planning practice and was predicated on assumptions of slow managed growth. In terms of land use, the draft plan proposed to retain a clear distinction between the core functions of the Central Area for industrial purposes and peripheral functions of outlying suburbs for self-contained residential communities. The draft plan also favoured low-rise buildings over high-rise constructions, citing cost and traffic congestion as liabilities. The draft plan was further refined and formally approved in 1958 as the Master Plan (Figure 3)—Singapore’s first statutory land use document.

The 1958 Master Plan provided a comprehensive island-wide development framework for a projected population of two million in 1972, by identifying three new town sites in Jurong, Woodlands, and Yio Chu Kang as well as prescribing maximum permissible net residential densities (in persons per acre) for planning districts within the Central Area. The architects and planners of the 1958 Master Plan, however, did not anticipate that Singapore’s rate of growth would quickly outnumber their projections, nor did they envision the series of political developments that would alter the course of Singapore’s colonial history and consequentially pave the path towards full independence as a Republic.

Figure 3. 1958 Master Plan—Singapore’s first statutory land use plan.

Source: Urban Redevelopment Authority.

The Road to Independence: Challenges and Opportunities

In 1959, I returned from my architectural and town planning studies in Melbourne to Singapore at a time of transitional change. Singapore had achieved status as a self-ruling State through a democratically-elected government in 1959. The newly-established government was confronted with several major challenges, but the focus on three key priorities would set the stage for Singapore’s breakaway from poverty and disorder. The first and most immediate priority was to resolve the acute housing problem. The SIT could only manage an average of 1,700 housing units per year during the post-war period when the population had already exceeded one million (Teh, 1969). A new institution named the Housing and Development Board (HDB) was therefore created in 1960 to replace the SIT.

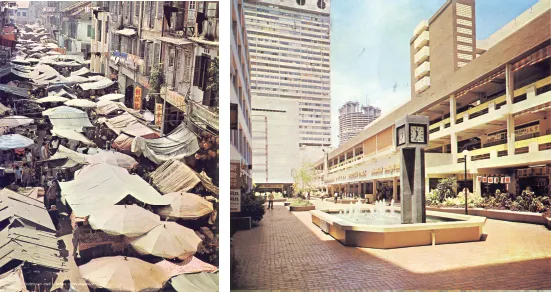

Secondly, Singapore could no longer depend on her natural hinterland or rely solely on her regional port activities for sustained economic stability as more land was required to accommodate the growing population. In addition, unemployment was on the rise, resulting in a burgeoning informal sector comprised of itinerant hawkers and petty traders working in precarious conditions (Figure 4). Economic advancement therefore became a priority which set in motion the creation of a statutory board, the Economic Development Board (EDB), in 1961. As I will later illustrate, there was to be great strategic cooperation between the domains of urban planning and economic development that helped spur Singapore’s progress from third world conditions to a developed nation.

Figure 4. Illegal hawkers and traders once plied the streets of Chinatown (left). A specially-designed shopping environment at People’s Park Complex, a URA sale of site development, provided modern facilities for vendors (right).

Source: Urban Redevelopment Authority.

Lastly, when Singapore gained full independence as a Republic in 1965 following her separation from Malaysia, the newly-established government led by then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew focused on nation-building for a population that was approaching two million. Paradoxically, this pressure drove the government to new heights of courage such that opportunities could be grasped and bold visions adopted, in this way, allowing dynamic and effective changes to ensue. In the next section, I relate my experiences on three bold urban programmes that I believe paved a critical path for Singapore’s transformation and modernisation.

A Young Nation with Bold Urban Plans

In Singapore’s early years as a young nation, there were hardly any trained architects. For the most part, the transfer of design and planning knowledge was passed down from colonial administrators to local technicians and draftsmen. When the SIT dissolved upon the establishment of the HDB, a large number of British architects and town planners left Singapore. However, a small cohort of freshly-qualified architects had just returned to Singapore. I also returned along with this cohort as a graduate of architecture and town planning, and I initially j...