![]()

Part One

Modernism in German and Irish Church Design

Kathleen James-Chakraborty

The reforms of Protestant and Catholic church architecture begun in Germany during the Weimar Republic (1919–33) took firm hold there in the post-war period. From here they were exported to Ireland and in turn, in part through Irish channels, disseminated around the world. The opening four chapters in this volume chart this story from the 1940s through the 1970s. Kai Krauskopf reminds us that a straight line cannot always be drawn from the experiments of the 1920s in German church construction through to the new churches erected after the Second World War. Instead many of these buildings bore the imprint of ideas about community developed in the secular setting of the Nazi party. The best new German churches, however, also required a fitting new approach to the design of church furnishings and ecclesiastical art. Here Imogen Stuart, who was trained in Germany and continued for many years to contribute to exhibitions of sacred art held there, proved the perfect professional partner for the Irish architect Liam McCormick, whose Catholic churches in Donegal numbered among the most important new churches on this far edge of Europe. Carole Pollard documents the fruits of their collaboration. On the opposite side of the island, as Ellen Rowley reminds us, Andrew Devane formulated his own response to the changes in worship, and thus also in church design, mandated by Vatican II. It, too, was informed by German precedent, although Devane, who worked for the most part in more established suburban settings, foreswore the plastic exuberance and self-conscious archaism embraced by McCormick. Finally, Lisa Godson demonstrates the global reach of the Irish Church and the degree to which its far-flung outposts provided devout Irish architects with the opportunities to experiment that they were not always able to find at home. Focusing on Pearse McKenna’s work for the Kiltegan Fathers in Nigeria, she establishes the degree to which pragmatic factors, including climate, cost and access to technical expertise, also influenced the construction of their designs.

![]()

1

Architects Debate Contemporary Church Building: Post-war German Sacred Architecture, 1945–60

Kai Krauskopf

1957 IBA Berlin: Continuity of the international style

At the conference ‘Protestant Church Building Today’ in 1957, held on the occasion of the International Building Exhibition (IBA) in West Berlin, Otto Bartning, the architect who had organized the event, claimed to build churches ‘with the given resources of today, in the modern language of today’. Instead of being designed in relation to the urban context as a representation of religion, Bartning furthermore declared ‘a church should be built from the inside out – from the intellectual and spiritual centre’.1

Bartning, who had led the progressive wing of architects building Protestant churches in Germany since the 1920s, now promoted two new church prototypes at the IBA. Willy Kreuer designed the Catholic Parish Church of St Ansgar on a parabolic floor plan with walls of precast concrete, while Ludwig Lemmer erected the Protestant Kaiser-Friedrich Memorial Church with transparent walls, porthole windows and a suspended aluminium ceiling (Figure 1.1). Presented as prototype buildings for the church architecture of tomorrow, they were part of the IBA showcase of modernity, which was planned by the leaders of the German architecture avant-garde of the 1920s such as Walter Gropius and Gustav Hassenpflug, along with the celebrated stars of contemporary international architecture, including Alvar Aalto from Finland and Oscar Niemeyer from Brazil. At the IBA, apartment blocks were built as cubes and rectangular boxes on concrete columns, and as high-rise buildings or flat-roof bungalows. Instead of traditional housing forms, they used obviously completely new designs, as did the two church architects.2

Figure 1.1 St Ansgar Catholic Church, Interbau Exhibition, Willy Kreuer, Berlin, 1957.

Source: Richard Biedrzynski, Kirchen unserer Zeit (Munich: Hirmer, 1958), Figure 59.

When Bartning declared that a ‘new church today means a modern church’ can a higher purpose inherited from that of heroic history of the white-walled modernism of the 1920s be discerned in the modern church building? Today the churches of the 1950s are visible everywhere, but research on them does not adequately show that instead of the idea of a new, specifically modern beginning, the architecture of many of them invoked concepts of transcendence that were present already before and during the Second World War. The question is whether these structures thus conveyed ideas that originated outside church design and were associated with very different politics than the emergence of post-war democracy. While they claimed to fulfil the liturgical reform of the first half of the twentieth century in their church buildings, many of their architects in fact focused on developing symbols of communality that would transcend confessional and ideological boundaries.

A comparison of statements made by the architects of such churches reveals the potential and characteristics of German church architecture in the first half of the twentieth century and helps answer these questions. In particular, against the background of escalating conflicts in the 1920s about the role and form of domestic architecture in Germany, what kind of requirements did architects propose for the task of church construction both before and after the Second World War? My selection of the texts upon which this chapter is based is limited to articles from architects who contributed their statement in the new context of an expanding church literature in the course of the re-confessionalization of the Federal Republic of Germany after 1949.

The rejected church architecture of the nineteenth century

The Second World War created an increased need for churches. In 1949, architect Gerhard Langmaack, who designed many churches, wrote of 1,200 destroyed and 6,000 damaged Protestant churches in Germany; the situation was little different for Catholics.3 After 1945, planners were faced with an extensive heritage of Neo-Gothic and Neo-Romanesque buildings from the nineteenth century, whose steeples had studded the older suburbs of large cities before the great destruction caused by the bombing. This architecture was now considered outmoded. Langmaack, who addressed the reconstruction of such churches in Hamburg, spoke of parishes with ‘the most liberal attitude’, in which the content of the religious service was no longer considered credible, ‘because the external appearance of the churches were unbelievable’.4 The turn towards international modern architecture was connected with a clear rejection of this nineteenth-century past. For instance, Willy Kreuer’s site plan for the IBA, which featured flowing green areas dotted with high-rise residential buildings, consistently rejected the previous densely built-up Wilhelminian district it replaced. And although local Protestants called for the faithful reconstruction of their Neo-Gothic church, it was in the end replaced by an entirely modern structure.5

The ‘Notkirchen’ (emergency churches)

This desire of many communities, to restore the old, which had been destroyed, to its previous condition, appealed to many of those responsible for Protestant art. Although the architect Winfried Wendland noted that this was ‘quite understandable’, he believed that the present day with its new tasks required a different design. ‘The Gothic form is an expression of a particular time which may not be repeated’, he co ncluded. ‘It would be artistic dishonesty if we pretended that nothing had happened since this was why all these churches had to be transformed in the future.’6

The written record suggests that this opinion was shared by almost all of the architectural community during the reconstruction period. The Notkirchenprogramm of emergency replacement churches developed in 1947–51 by Bartning as a response to the devastation of the war appeared to be the first step in replacing the supposedly outmoded heritage through modern construction (Figure 1.2). Langmaack praised this scheme as historically unique, as it satisfied not only the need for worship, but also created church interiors that would be remembered as ‘a one-time freeing up of tradition’ in church construction, ‘which would have a significant influence and would be a sign of the times within the Protestant Church’.7

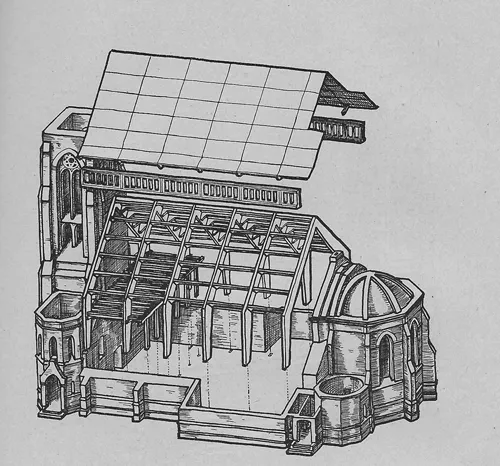

Figure 1.2 Emergency Church of St Mark, Otto Bartning, Hamburg, 1947–51.

Source: Gerhard Langmaack, Kirchenbau heute. Grundlagen zum Wiederaufbad und Neuschaffen (Hamburg: Agentur des Rauhen Hauses, 1949) 71.

Bartning’s Notkirchen program included three types of simple structures that could be constructed quickly from debris. The prefabricated forms of L-shaped laminate beams, carrying the roof as well as walls, determined not only the shape of the church’s exterior but also the interior, where their regular intervals established a rhythm. Using such a clearly highlighted serial construction, Bartning responded quickly to the post-war circumstances and realized forty-seven buildings. Some of them were installed directly in the ruins of the old church as substitute naves. For instance, taking advantage of the remaining tower and the remains of walls of the St Mark’s Church in Hamburg, Bartning and Langmaack fused a functionalist modern structure with nineteenth-century church architecture.8 Very different from this coexistence of old and new for entirely pragmatic reasons were the St Rochus Church in Dusseldorf and the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin. These were built a few years later and created a material and programmatic dialectic between the ruin and new architectural styles. When a building was not completely cleared in favour of a new church project, the architects now replaced the supposedly inadequate rectangular nave of the historicist church with a completely new spatial conception. In 1954, Paul Schneider Esleben built a new nave in the unusual form ...