![]()

1

Children’s Transitions in Everyday Life and Institutions: New Conceptions and Understandings of Transitions

Mariane Hedegaard and Marilyn Fleer

Introduction

Children’s transitions into different institutions, such as when starting school, has always been an important topic in research and something that is of great interest to families as they support the transitioning child into the different institutions they attend and life course events they experience. Many have written on this topic and have made important contributions to understanding how children’s transition impacts on well-being (e.g., Cavada, 2016; McLelland & Galton, 2015) and is being experienced in different countries (e.g., Ballam, Perry & Garpelin, 2017a), in different institutions (e.g., Wilder & Lillvist, 2017), and during different life course events (e.g., De Gioia, 2017). What has been common to most of the writing on this topic, has been the theoretical work of Uri Bronfenbrenner: in particular his early work on ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and his later work on a bio-ecological model of child development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006) have framed how researchers have come to understand children’s transitions in everyday life and into different institutions.

A great deal has been learned through these studies about how children experience transitions. In declaring an ecological or a bio-ecological model of child development, researchers have theorized their results in relation to the systems in which the children are found (Dockett, Griebel & Perry, 2017). Results have been explained through detailed descriptions of how societies shape the ways in which a child experiences the institutions that they attend and how their pathway into these institutions during moments of transition are experienced (Dockett & Einarsdottir, 2017). We now know a great deal about how systems frame and create institutional conditions for children from this important work (Ballam, Perry & Garpelin, 2017b).

We have also seen a merging of theoretical traditions to support deeper theorization and research on transitions. For example, Pollard (Lam & Pollard, 2006; Pollard & Filler, 1996) has integrated Bronfenbrenner’s social constructivist approach with Vygotsky’s dialectic approach and, through this, has foregrounded the child’s role in creating conditions for their own learning. Through a series of case studies he followed children from four to seven years of age, studying how children themselves contributed to their own learning conditions as they entered into a new institution. Important theoretical work has also been undertaken in relation to young people and adults in this respect (see Stetsenko, 2017), but more needs to be known about children’s agency and perspectives in creating conditions during their transition for their own learning and development.

In this book, the contributors have all drawn upon Vygotsky’s cultural-historical theory of transition, seeing it as central for understanding child development. Transition in children’s life course takes place when a child enters a new practice with new demands (Bozhovich, 2009; Elkonin, 1999; Vygotsky, 1998). This may lead to tensions and in some cases crises may result in ruptures, which means that earlier competences and motives disappear, and become integrated and subordinated in relation to other competences and motives. This book orients the reader to this perspective, while also drawing attention to how transition can be conceptualized as taking place when children move between everyday practices and everyday settings (Hedegaard, 2016; Hedegaard & Fleer, 2013). These everyday transitions are not conceptualized as ruptures, though they may lead to tension, but are viewed as important for children’s development. This perspective foregrounds the need for children and their carers to be conscious of the differences in activities in the different settings.

By going beyond a bio-ecological model of transition, we show in this chapter and throughout the pages of this book, how children contribute to their own transitions through their motive orientation to new institutional practices before entering into them. We also show how demands and intentional interaction during the new activities shapes their own conditions. Rather than seeing transitions as problematic, we argue in line with Vygotsky’s theory of development that transitions can give new and important conditions for children’s development. By taking this agentic stance, we argue that new insights into transitions can be gained. This is in keeping with Stetsenko’s (2017) life course work on what she has called a transformative activist stance. Stetsenko introduces a dialectically recursive and dynamically co-constitutive approach to development in which ‘people can be said to realize their own development in the agentive enactment of changes that bring the world, and simultaneously their own lives, including their selves and minds, into reality’ (p. 31, original emphasis). In this reading of agency, development is a transformative process where histories and future enactments are recursively constituted. This conceptualization of development is not biologically deterministic, or viewed as a progressive transition of the child into a cultural community, but rather it conveys a sense that ‘development is about participating yet is also, and even more critically, to contributing to transformative communal practices’ (p. 34). Captured in her concept of activism, her work (like the chapters in this book), gives different insights into the concept of transition to that which is currently foregrounded in the literature. Likewise, the contributors to this book draw upon different theoretical tools – notably, cultural-historical concepts.

A cultural-historical conception of transitions

What is central for a cultural-historical perspective on development is the periodization of children’s development that is connected to their transition from one institutional practice to the next. In understanding these transitions, Vygotsky described critical periods related to change in external conditions. According to this theory, periods in children’s development have three phases: 1) a stable phase, 2) a critical period with ruptures that leads to 3) a new constructive period of neo-formation. In the critical period, a child becomes relatively difficult in comparison with how they previously entered into the practice traditions in everyday life. There is disintegration and ruptures of what has been formed in the preceding stages. During these critical periods the child does not so much acquire, but loses what s/he has acquired earlier. Neo-formations serve as the basic criterion for driving children’s development from one age period to another.

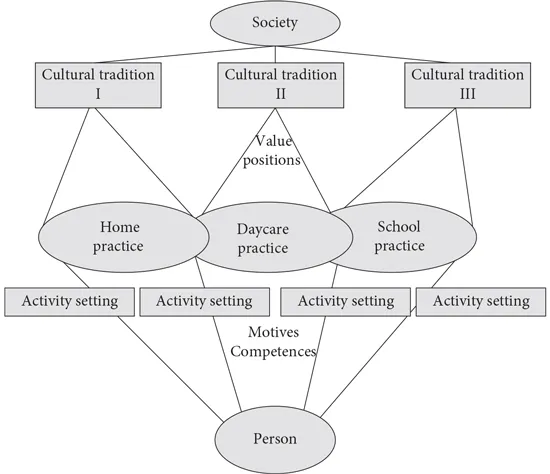

Analysing a child’s entry into new practice traditions in Vygotsky’s theory is left at the institutional level (e.g., school or home) and not necessarily across different institutions or at the societal level. In drawing upon Hedegaard’s (2014) model of transition (Figure 1), this dimension is captured as the child’s movement occurs between the different institutions s/he attends in the context of societal values. In relation to this we also have to conceptualize, for example, when a child starts school, s/he could also be going to after-school care, to different clubs or after-school events, while actively participating in known home practices (Hedegaard & Fleer, 2013). From this perspective, researchers who have contributed to this book have paid close attention to the child’s intentions, as s/he enters into the different institutions (zigzagging), while also examining how societal expectations are realized at the institutional level through rules, values, policies, funding etc.

To fully understand the conditions for children’s lives one has to identify the institutional practices a child participates in. Also needed is a close study of the activities that dominate within institutional practices, where the demands that practices put on children, the possibilities these give for activities and how children act in these activities, can then be understood. Children’s learning and development in families, kindergarten and school takes place through children’s engagement in these activities, but children also recreate activities in specific activity settings, alone or together with other people (i.e., parents, siblings, teachers and classmates). New demands and new motives arise from entering a new institution or when moving between several institutions over the same period, such as home and kindergarten or home, school and day care.

The focus in this book is on children’s transition between institutions, such as starting day care, leaving the safety of home for several hours to enter day care, or moving from home to school every day for many years. Changing participation from one activity to another is the central aspect, because both demands and motives changes through this transition. Transition between activity setting also take place in the same institution, as when a child in school moves from one subject class to another, or when a child in kindergarten moves through the daily schedule of the different activity settings, such as arrival time, play time, lunch and outdoor activities. Transition is a key concept for understanding development: both in relation to possible developmental trajectories and in relation to daily transition between the different communities in home, day care and school.

In Figure 1, the relation between societal conditions, traditions and values, institutional practice with its activity settings, and a child’s activities, are depicted. This is a model of the general structural relations that may be used to analyse children’s learning and development. In concrete terms, the dynamic between these relations are the centre of our focus, as we will illustrate by following children in different settings and different activities as they transition between them.

Figure.1 Illustration of the relations between society–practice and persons with cultural traditons and activity settings as mediating links

This model frames how the book has been organized, and through this, shows how the concepts in this model contribute to analysing the transitions discussed in the specific chapters.

Different dimensions of transition are illustrated through the different chapters, where authors have primarily referenced concepts shown in Figure 1, and where the content of the chapters collectively contribute to a new way of understanding transitions.

The book is organized into two sections. The first section contains chapters that view transitions and what it means for children’s development from a societal perspective. The second section contains chapters that depict transitions from the children’s perspective as it takes place through moving between different activities, where children become aware of different ways of interacting. Together, the two sections explicate a cultural-historical conception of transitions, while at the same time introducing new insights and understandings through this reading of transitions.

Part 1: Societal trajectories: Children’s life courses

Transitions in children’s life courses are related to the possible trajectories that a society provides (Hedegaard, 2012; Hundeide, 2005; Rogoff, 2003). For children in most societies these societal trajectories imply compulsory schooling; in some places though, other trajectories dominate where children are expected to participate in work from a very early age (Hundeide, 2005; Rogoff, 2003). In contrast to this, in several Western societies there are trajectories that provide opportunities and create expectations for children’s participation in childhood education from a very early age. In Danish society, it is expected that children start in nurseries at around one year old and in the kindergarten when they are three years old. Participation in kindergarten practice is not obligatory but is advocated by the state and 98 per cent of Danish parents choose this possibility for early childhood care and education. Transition in children’s life courses from an early age is central to their development, because the new institutions they participate in orient children to new demands and new motives that are essential to becoming citizens in society.

Entering school is obligatory in most nations, and many people who care for children (parents, grandparents and early childhood teachers) see schooling as a way of gaining social status in society (Wong & Fleer, 2012) and to develop the competences needed to participate in their community (Hedegaard & Fleer, 2013; Rogoff, 2003). In nearly all societies, transition to school is not an event that children can avoid; it is a must for being a child today. Transition to school may be something children are oriented to in many countries long before they start school. Both in narratives about being a child and in everyday practice children are confronted with the event of starting school, and by the activities that take place in early childhood education. It is common for many young children when meeting a new adult and being introduced to the family to be asked: ‘Are you going to school?’ or, ‘When do you start to go to school?’

In the following excerpt of two girls playing at going to school, we can see how children start to have ideas about the pending school demands that leads both to excitement at what is happening and to anxiety about managing these new demands.

A morning setting in January, in The Oak Tree kindergarten

There are activities going on at three of the tables in the room. Two pedagogues sit together at one of the tables with some of the youngest children, who are drawing. At the largest table, two girls, Else and Laila (both five years) are playing with small dolls. They have two extendable doll’s houses. They move some dolls between the houses and talk.

Laila says, ‘We need to relax’ and ‘When are we going to school?’

Else: ‘Oh, why should I be late? I do not want to. Princesses come in time!’

Laila: ‘You are right in time to get to school, no one is there yet!’

Laila make her voice brighter and says: ‘The prince must also attend school (she moves a character who is a man in armour on horseback).’

Between the two girls are now collected seven dolls.

The girls then negotiate with a boy about the exchange of a toy aeroplane for more figures for their doll’s houses. They go with him to another room to get the figures.

Coming back, Else says to Laila: ‘Come on, now we will play.’ She takes Laila’s hand and leads her back to the table.

The girls move the figures around. Laila mentions the word ‘detention’.

Else: ‘We should not be in detention, because we were so decent and did everything the teacher said.’

What this example shows is that children may be oriented to activities in school practice that they only vaguely know. The two girls have expectations of what is going to happen; expectations that are mixed with excitement and anxiety about what is expected of them, rather than towards what they will learn.

Hedegaard and Munk (Chapter 2) question this orientation, which is already seen in kindergarten. Their project contains a critique of the conditions that the Danish government creates for preschool children and teachers with demands for learning activities in kindergarten that orient them to school learning, instead of involving them in play activity where they may create competences of imagination and planning that children need when at school, undertaking abstractions in literacy and oral activities. The schoolification of early childhood education is increasingly being seen in many Western countries, where governments are placing great demands upon teachers for a more formalized programme to improve the academic outcomes of children (see Fleer & van Oers, 2018). In discussing this problem in Denmark, Hedegaard and Munk argue that orienting children towards school learning instead of learning to play excludes children from acquiring foundational life competences of social interaction and emotional imagination, competences that kindergartens have traditionally provided as part of their practice.

Transition from one institutional practice to another, such as leaving kindergarten and entering school, leads to a restructuring of children’s relation to their environment that may result in some kind of crisis. Since most children enter into these crises they should not be seen as harmful but as part of growing up in a culture. Vygotsky (1998) and Elkonin (1999) describe what happens to children through this transition as crises because the child’s way of relating to his or her environment does not fit with the new demands. A kind of destruction or restructuring of the child’s competences and motives has to take place leading to new competences and motives. Depending on how the environment is created, these crises will be more or less obvious during the child’s transition. The crises in one institution, such as home, may be the result of new demands when a child is entering school. Hedegaard (2018) describes how a family has small daily crises created by a child entering school. Emil, a six-year-old boy in a family with four children, has just started in the transition class in school, class zero. Through a description of conflicts that Emil creates in his everyday activities we can follow how his relationship with his parents and siblings changes and that these changes imply minor crises that in many ways are created intentionally by the child, because he is oriented towards a new position in the family by goin...