![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Textiles

MARIA HAYWARD

INTRODUCTION

In 1606 Thomas Dekker wrote The Seven Deadly Sinnes of London. He described clothes-conscious young English men dressing in fabrics and fashions drawn from far and wide:

His codpiece . . . in Denmarke, the collor of his Dublet and the belly in France; the wing and narrow sleeve in Italy; the short waste hangs over a Dutch Botchers stall in Utrecht; his huge slopes speakes Spanish; Polonia gives him the Bootes . . .1

While he primarily linked different styles of dress to different geographical locations, Dekker could have made his point equally well had he listed where their various materials, trimmings, and accessories had come from. Like many other countries, England was tightly bound into the international textile trade which combined tradition and innovation. This chapter is divided into five sections—fibers, textile production, other materials used to make and decorate clothing, economy and trade, and dyes—to demonstrate why textiles were so important in early modern society.

FIBERS

Textiles woven from natural fibers were the most important of the materials used to make clothes of the sort described by Dekker. The types of textiles an individual selected for themselves and others would reflect their social status and disposable income. Their choices would also depend on the garment they were ordering, whether it needed an outer fabric, interlining, lining, and padding, and on the drape and handle of the textile. One example will serve to illustrate this point. On October 14, 1510, Henry VIII gave John Williams, one of his footmen, a set of clothes as a wedding gift. The clothes needed to reflect the status of both Williams and the king, while also being appropriate to the specific occasion where they would be first worn. Williams was given the following: a gown made from five yards of tawny cloth at 5s per yard, and furred with 139 black lambskins at 3d each, six yards of black damask for a jacket at 7s a yard, three yards of black velvet for a doublet at 11s a yard, three ells of linen for a shirt at 14d the ell, a pair of scarlet hose costing 8s and a bonnet priced at 3s 4d.2

The first thing the list highlights is that two main types of fiber were used to make fabric in the early modern period: these were either proteinaceous or cellulosic. Protein fibers included wool, silk, mohair, alpaca, angora, and cashmere, the most common being wool and silk, while linen and cotton were the most popular cellulosic fibers (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1: A woman’s linen jacket embroidered with silk and metal thread and spangles, c. 1600–25. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

These could be woven into fabrics with the same fiber being used for the warp (the vertical threads) and the weft (the horizontal threads) or into union or mixed cloths where one fiber was used for the warp and another for the weft.

Williams was given a gown, a mark of male status, which was made from wool cloth. This is not surprising because wool was arguably the most important fiber in the early modern period, both in terms of the quantity produced and its value to the economy. This is linked to two factors. First, the wool fiber is warm, soft, crimped, grows in clusters, does not wet easily and covers the body of sheep (Ovis aries). Second, sheep were reared in huge numbers in Europe at this time. It also was suited to Williams’s social status as a man from the lower middling sort. The quality of the wool varied greatly depending upon the variety of sheep it came from, while the value was influenced by market trends. The Townsends, a landowning family in Norfolk, owned between 8,000 and 9,000 sheep in the 1480s.3 The main challenge to English wool came from the very soft, fine wool of the Spanish merino sheep which were raised on the Medina del Campo in Castile. It was exported via Seville and Burgos to Bilbao and then sent to Flanders.4 Sheep farming and wool production were very important in Spain with 2,000,000 to 3,000,000 sheep migrating each year as part of the pattern of transhumance. However, the Mesta, the sheep owners, supplied loans to the crown resulting in a serious imbalance of trade in Spain with emphasis placed on wool rather than cloth. This hindered the development of weaving in Barcelona and Valencia.5

Other animal fibers were popular, the most important of these were mohair, the silky hair of the Angora goat (Ankara keçisi), cashmere from goats in Kashmir and Nepal, and the hair of the Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus). The guard hair and the undercoat were used or were mixed with wool. These camels were native to central Asia, ranging from Turkey, to Siberia, Mongolia, and China but there was increasing demand in Europe for these fibers. In 1637, the mayor of Canterbury objected to the number of Walloon weavers working in the city and the “late abundant ymportacion of mohaire or turkey yarne” and the “greate importacions of late yeares from Turkie of yarnes made of camells haire.”6

Black silk damask and silk velvet were selected for Williams’s jacket and doublet, and the desirability of silk over wool is reflected in the price per yard with the cloth costing 5s while the damask cost 7s and the velvet 11s. The high cost of silk was linked to several factors including that the silk worms (Bombyx mori) fed only on white mulberry leaves which were native to China. Silk worms produce two silk filaments coated with sericin; once the sericin is removed the silk fibers are fine, soft, long, translucent, and lustrous, qualities that are transferred to the textiles woven from them. Sericulture was widespread in the early modern world with silk worms being raised in China, Japan, and Korea, as well as in India, although the silk from Bengal was quite poor quality.7 Silk was raised in Andalusia and Sicily from the eleventh century and by the 1500s sericulture had spread to Italy and more specifically to Lombardy, Lower Piedmont, Tuscany, and the Veneto (Figure 1.2).8 By the seventeenth century, raw silk was being produced in France and James I wanted to establish silk production in England and in Jamestown, Virginia, by encouraging the planting of mulberry trees.

Moving to the cellulosic fibers, Williams was given a linen shirt. Linen was made from the flax plant (Linum usitatissimum) which produces a thick, strong, hygroscopic, bast fiber, which has little elasticity. Between 1450 and 1650, flax was predominantly produced in Western Europe, with the area of production moving towards Poland and Russia over time.9 When Fynes Morrison (1566–1630), a traveler and writer, stopped in Haarlem in the northern Netherlands in 1593 he observed that “the Citie makes great store of linnen clothes, and hath five hundred spinsters in it.”10 In contrast, production in England and Ireland was relatively small scale. In part this was because flax is very demanding on the soil, so it was planted in rotation with other crops to help keep the soil fertile. It was also labor intensive to produce because the plants needed regular care and weed-free conditions.11 However, the English government used legislation to promote flax cultivation reflecting the value it attached to linen. An act passed in 1531 required that one rood (a quarter of an acre) of every sixty workable acres was to be used to produce flax and hemp.12

FIGURE 1.2: A piece of velvet cloth of gold with loops of silver-gilt thread, Italy, c. 1475. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The one fiber which did not appear on Williams’s clothing warrant was cotton, and this is typical of other warrants issued by Henry VIII to his household and of his own clothing orders. However, this does not mean that cotton was unknown in early modern Europe. Raw cotton (Gossypium), sometimes called cotton wool, is a seed fiber which is very fine. It has a short staple or standard length, it is very absorbent, and it can be used as padding as well as being spun into yarn. In the 1500s, India, Persia, Syria, and Egypt were producing raw cotton which was exported by the Portuguese and the Italians, their key market was southern Germany, to supply the weaving industries in Swabia.13 Spanish settlers also found cotton being grown in Peru and Mexico in the sixteenth century, while John Chardin, a French jeweler and traveler, found cotton growing in Safavid, Persia in the following century. More significantly from a European perspective, cotton was also grown in Calabria and Sicily, as well as in Spain in the area around Cordova and Seville. By the late 1600s, cotton was poised to replace wool as the most widely worn fiber in Europe.14

TEXTILE PRODUCTION

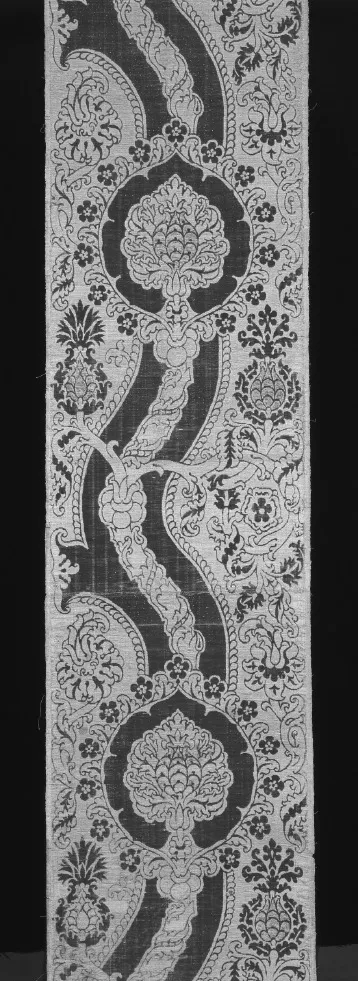

The account book of the royal household noted that all the materials used to make the clothes given to Williams were specially bought, indicating that there was a vibrant market for textiles in London. The selection of material and making it up into garments was the culmination of a lengthy and often complex process, the first stage of which was making yarn for weaving, or for sewing or embroidery. Yarn was spun using either a drop or hand spindle or the spinning wheel (the smaller flax wheel and the wool wheel). Spinning gave the thread twist, either to the left or right (known as s or z spun); when two or more threads of similar weight were twisted or plied together they would become stronger. Fancy threads included gimped thread which consisted of a core thread with another wrapped around it, often a fine metal strip (Figure 1.3).15

These threads were then woven into textiles on several types of loom, including the treadle loom where the shafts were lowered and raised using foot pedals.16 Draw looms, a more complex version of the treadle loom, were used to produce patterned fabrics from the sixth and seventh centuri...