![]()

1

Evocations of Place

This chapter explores the attachment of the poets of post-Mongol Shiraz and their immediate predecessors to the city in which they built their careers and eulogized their patrons. The poetry produced in Shiraz in this century and a half is rooted in a specific time and place and it is through topographical allusions to localities in and around Shiraz couched in extravagant praise, that the poets manifest their patriotic attachment and local pride. These loco-descriptive poems are infused with an intense love of place, demonstrating a dynamic, productive connection between spaces evoked in poetry and the reality of the politico-cultural situation the poets worked to fashion. The contextualizing effect of toponyms in localized poems of place is discussed here alongside the panegyric and political functions of allusions to metropolitan Shiraz, its gardens, meadows and pleasances, and Shiraz’s competitive relationship to rival cities of Iran and Iraq and regions of the broader Persianate world.

The fabric of a city, its palaces, parks and other created landscapes can be read collectively as a stage for conveying regal power.1 In addition to shaping Shiraz’s built environment, its rulers displayed their power through patronizing panegyrics that conveyed Shiraz’s intoxicating allure, presented it as a welcoming abode of perfect bliss and established it once and for all as the source of the finest Persian poetry. In the fragmented political landscape of post-Mongol Iran, identification of the ruler with the city (and not a wider empire) led to a greater focus on Shiraz and its dependent territories as a ‘micro-state’ (not wholly dissimilar to the city-state in ancient Greece or Renaissance Italy).2 As Ingenito has argued, when poets mention their city in verse, they engage in ‘a speech act normally implying an encomiastic or celebratory function’.3 Persian poetry was largely produced in an urban environment where the city served as the pivotal platform of culture and hosted a nexus of patronage networks.4

When the poets studied here wrote about Shiraz, they did so deliberately and with the intention of conveying a particular impression about the city.5 When read with sensitivity to the political and patronage-related functions of evocations of place, seemingly hyperbolic or esoteric imagery can be deciphered to show how Persian lyric poetry of the period circa 1240–1400 actually contributed to the creation of its environment; poets chose to present Shiraz and the region of Fars, both to those attached to the local court and to those at rival cultural centres, as an earthly paradise at the heart of the Iranian world.6 How the poets achieved this goal and what the construction of such an image of Shiraz afforded them, are the chief topics discussed here.

Shīrāzīyāt: A local poetics of place

As city-based regimes, unlike the empires that had come before, the importance of the urban centre was proportionally greater in the post-Mongol context. Cities such as Shiraz lay at the centre of fragmented decentralized polities; each local ruler was a world-king and each regional capital was the seat of a court with imperial aspirations. Accordingly, each provincial court and its poets drew on local cosmological and mythical associations attached in the minds of their city’s inhabitants to nearby ancient ruins that functioned as lieux de mémoire or ‘sites of memory’ (see Chapter 4). Shiraz, unlike its chief rival, Baghdad, was largely spared the ravages of the Mongols and appears to have flourished for much of the thirteenth century. The Salghurids (1148–1282) nurtured local poets and provided refuge to literati such as Shams-i Qays-i Razi fleeing from Mongol attacks.7

From the Salghurid period on, poets produced a series of eulogies in praise of Shiraz in which the city, its environs and its inhabitants are extolled. These stand-alone lyric poems in praise of Shiraz the ‘city of knowledge’ (dār al-‘ilm, madīna-yi ‘ilm)8 can be called Shīrāzīyāt.9 Poets also incorporated topophilia into their praise odes, often in the form of a Shiraz-focused amorous introit (taghazzul). The poets’ explicit use of a set repertoire of topographical allusions forged intertextual bridges linking poems from distinct historical periods, resulting in time in a harmonized vision of Shiraz as the ideal city. Shiraz can stand for the city proper, the urban conglomeration, its suburbs, dependent villages, extramural garden belt and its rural, bucolic hinterland or even the whole realm of Fars.10 Praise for Shiraz may at first seem hyperbolic until we consider what travellers and geographers had to say about the city. In the twelfth century, Tusi praised Fars as a ‘blessed, fortunate, and flourishing clime’ (iqlīmī-st mubārak u farkhunda u ‘āmira); a land that boasts ‘abundant bounties’ (ni’mat-hā-yi farāvān).11 And in the thirteenth century, al-Qazwini (d. 1283) praised Shiraz for its ‘healthy air, fresh water, many good things, and abundant agricultural products’.12 The famous North African traveller, Ibn Battuta (d. 1377) visited Shiraz twice, first in 1327 and then again in 1347 during the reign of Shah Shaykh Abu Ishaq. Ibn Battuta remarks how well-built and superbly planned Shiraz is, how pious and chaste the city’s inhabitants are (in particular the women) and he rates Shiraz second only to Damascus among cities of the Islamic east in terms of markets and orchards. Ibn Battuta also mentions the sweetness of the water of the Ruknabad canal and the comeliness of Shiraz’s inhabitants.13

Writing in 1340, Hamdullah Mustawfi describes the city as ‘exceedingly pleasant’ (dar ghāyat-i khushī).14 He mentions the mild climate and Shiraz’s excellent grapes, fine cypress trees and the ‘lean’ (lāghar), ‘dark-skinned’ (asmar) majority Sunni populace. Mustawfi also notes that most of Shiraz’s wealthy ‘are outsiders’ (gharīb-and).15

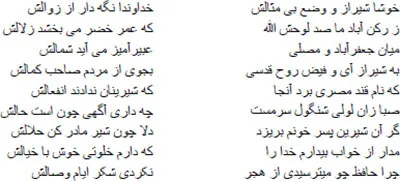

This admiration for Shiraz expressed in travelogues and local histories dovetails neatly with much of what we find in Shīrāzīyāt. Shiraz is one of those cities whose charm inspires attachment, pride and personal loyalty16 and the loco-centric poems produced in the city more than six or seven centuries ago still dictate how Shiraz is memorialized and imagined today. The most famous fourteenth-century Shīrāzīya is this poem by Hafiz:17

Blessed be Shiraz and its peerless situation!

O God, protect it from all deterioration!

May God protect our Ruknabad a hundred times

For its crystal waters bestow the life of Khizr.

Between the Ja’farabad quarter and Musalla promenade

Blows her north wind, mixed with perfume.

Come to Shiraz and, from its excellent inhabitants,

Seek the bounty of the Holy Spirit.

Whoever carried the name of Egyptian sugar there

Without being shamed by i...