![]()

1

BODY

MISE EN SCÈNE

In 1937, Stage magazine ran an advertisement for the perfume Chanel No. 5:

Madame Gabrielle Chanel is above all an artist in living. Her dresses, her perfumes are created with a faultless instinct for drama. Her perfume #5 is like the soft music that underlies the playing of a love scene. It kindles the imagination; indelibly fixes the scene in the memories of the players.1

The saccharine mawkishness of the passage should not be a complete deterrent, as there are several relevant themes latent within it, albeit not devised with any philosophical intention. It begins with describing Chanel’s art as living, implying lifestyle but also all the things that bring quality to the lived moment. Her creations add and assert a quality to life that makes life more acute. Their “drama” insists upon play and performance; they set the wearer on a stage of style and desire. Chanel’s famous perfume thrusts its users into a narrative that is then burned upon their respective memories. The last word, “players,” leaves no doubt about the way in which Chanel brings her consumers into a realm of enactment. Chanel was the first couturier not only to create a signature fragrance, but also to use it to fill her fitting rooms at the rue Cambon with its ambience, a practice revived by recent designers such as Thierry Mugler, whose boutiques are aggressively “Angelified” as a branding exercise to promote his perfume, Angel.

With such gestures and ruses, Chanel was one of a number of designers who effectively helped to inaugurate the scenic model of fashion that has gained in density and sophistication ever since. Perfume’s very intangibility and ineffability, yet the power of the olfactory organ to evoke and connote, brings us directly to the very core of fashion as encircled by images, and the extent to which glamour and prestige are abstract and immaterial. Contemporary advertising of perfume drives this notion home, for any effort to describe the perfume, which would be absurd, is replaced by an arbitrary association with a place or a celebrity that is made to seem indelible. Whether it is the mystique of a place or the magnetism of a known personality, the perfume is a confirmation of desirability and a fabricated world made abstractly concrete. Whereas clothing and accessories are concrete and have their uses, perfume’s only palpable elements are its color (if any) and the shape of the bottle it is in. Yet it is precisely because perfume is untethered to the world of things that makes it the optimal example of the narrative worlds that circulate around commodities. For the rise of fashion display is indissolubly part of the rise of commodity culture and the spectacle, from the birth of the modern department store to the birth of film. The mise en scène of fashion is to be viewed together with the beginning of large-scale public exhibitions, such as the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, and the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855. National display is historically symmetrical with personal display. Personal mobility and reinvention is to be understood only according to the inventions of fashion itself, whereby the garment’s semantic strength was owed to innumerable other properties brought to it through its presentation and display.

Exhibitions, arcades, and department stores

In the days of artisans and guilds, there was a more “authentic” relationship to manufacture and selling, with the artisan selling the things they made in the shop designated for that purpose. In pre-modern times, those who only sold and did not make were peddlers, who were deemed inferior to those who made things. But by the nineteenth century, salespeople, the middlemen between producer and consumer, were often those who benefited more than those at the center of production. It became the skill of salespeople not only to act convincingly, but also to provide environments that cast prospective consumers into places commensurate to dreams. This was the insight of Walter Benjamin, who in his vast and unfinished work, The Arcades Project [Das Passagen-werk], perceived the close connection between museums, places of leisure (clubs, spas), and arcades. In the arcades, shopping need not be entirely a material experience but was a mental one as well (Figure 1). Benjamin refers to “Dream houses of the collective: arcades, winter gardens, panoramas, factories, wax museums, casinos, railway stations.”2 Moreover, “Arcades are houses or passages having no outside—like the dream.”3 In another entry, Benjamin writes of “the dreaming collective, which through the arcades, communes with its insides. We must follow in its wake so as to expound the nineteenth century—in fashion and advertising, in buildings and politics—as the outcome of its dream visions.”4 Benjamin saw an undeniable connection between what his friend Ernst Bloch would characterize as hopefulness for collective better life in the configurations of modern life. Modern life placed people and commodities in settings that literally staged the promise of greater possibility.

Figure 1 The Arcade, Cleveland, Ohio.

In his chapter on the dream in Benjamin’s work, Eli Friedlander insightfully writes that:

An environment is essentially different from an object given to consciousness, it cannot be simply identified, broken into parts, isolated, and studied. The manifestation of the incorporation of an environment in consciousness would make certain images stand for or gather the amorphous surroundings. These are the dream images.… The deformation of the dream images is the manifestation of the internalization in the arcades. The arcades provide a gathering point in wish images of the yet-to-be articulated environment of life.5

For Benjamin, these dream-images were meant to transform into a new configuration of consciousness that could lead to an “awakening” to fulfill the utopian goals of humanity.6

Fashion, however, could also be distrusted because it manipulated such dreams and desires for its own ends. The utopianism was built into its rhetoric but not as an earnest philosophical program. And the conflation of commodities with dreams has relevance to this day, but was most evident when it came to fashion. “Fashion,” Benjamin remarks, “like architecture, inheres in the darkness of the lived moment, belongs to the dream consciousness of the collective. The latter awakes, for example, in advertising.”7 Benjamin, although revealing at times an ambivalence to fashion, was also encouraged by his friendship with Helen Hessel, with whom he visited fashion shows and whose book Vom Wesen der Mode [On the Nature of Fashion] he read with great interest and cited in his notes on the arcades.8

Benjamin’s musings on the panorama will also prove relevant to later, more contemporary examples of fashion installation. What makes Benjamin’s work significant is that it is the most developed and intricate set of reflections on the spectacle of modernity and the agonistic relationship between the perennial and ephemera. “The historical object,” note Howard Eiland and Michael Jennings, “citing past and future simultaneously, like any object of fashion, unfolds as palimpsest and picture puzzle.”9 Fashion exists together with and against other fashions, as well as the linguistic–historical conditions of placement, use, and association.

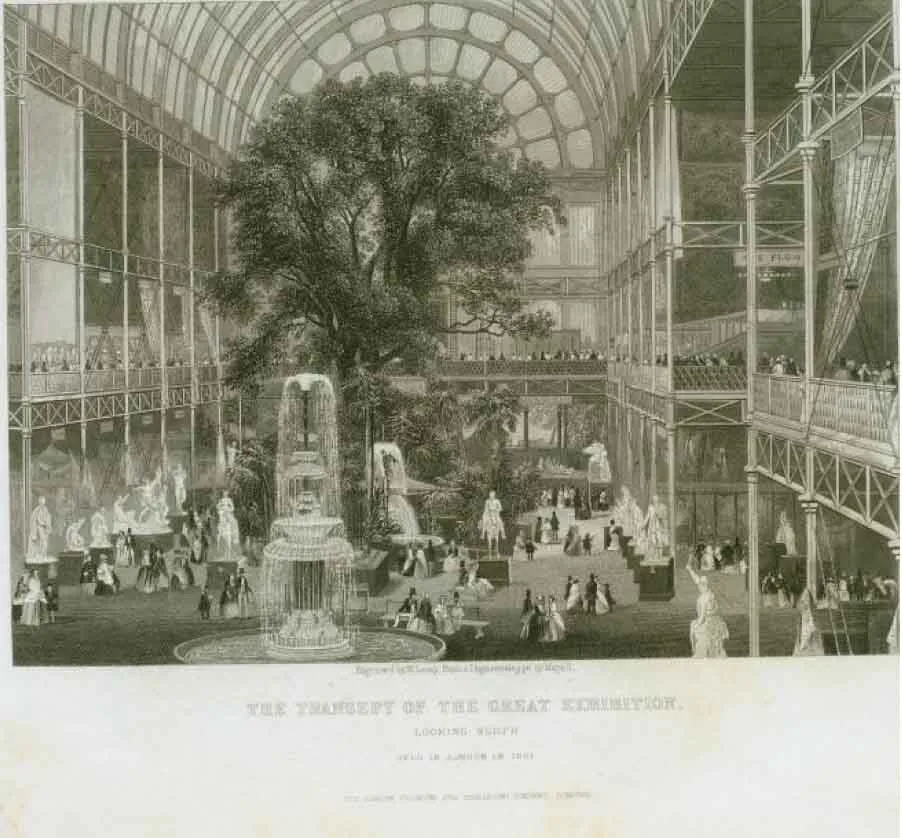

As a tendentious manipulation of ethnicity and history, the Great Exhibition of 1851 had a lasting effect on all manner of the ways things were displayed. Ethnicity was put on show, but just as preponderantly, fashion. On display were not only countless forms of ethnic dress, items of fashion, but also the public themselves (Figure 2). As Alistair O’Neill explains, the educative, even didactic, environment of the Great Exhibition proved appealing:

The premise of learning about fashion through its educational display was a new proposition that women’s interest titles sought to unpack, offering commentaries on articles of dress, textiles for dress and accessories displayed in the Great Exhibition distinct from those found in official and popular published guides. Another special quality is their captured sense of visiting the exhibition, as journey and route, attraction and edification, as an experience tailored.10

Figure 2 The transept of the Great Exhibition (looking north), held in London in 1851.

What the Great Exhibition helped to nurture and to isolate was the essential yet most elusive of constituents, namely that fashion is an experience that unfolds when bodies, clothing, and environments meet. It presented many items of clothing not for sale, but clearly with the intent of ensuring that they would be in the ostensibly different, but in fact deeply related, context of the store (Figure 3). Helped as well by the accompanying guides and the reports made on such displays in women’s magazines, the displays, while under the sobering guise of guidance and instruction, were sites of temptation, where visitors could gather for themselves their own internal wish images which they would then realize for themselves outside the exhibition. To extrapolate Benjamin’s insight, the more self-evident dream-world of the exhibition helped to mask the dream-world of the shopping arcade and the department store.

By the opening years of the twentieth century, the expectations around the level of fanfare in the European Great Exhibitions reached new heights, as had the zeal with which such expectations were met. For the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, fashion was one of the central features, that is, fashion and its surrounding mood and narrative settings. This was the exhibition that sought to launch France as the leader of the pan-European, if not international, style of Art Nouveau, and was therefore rich in design and the inherent stagecraft of the style that melded eighteenth-century nostalgia with the still relatively new frenzy for Japonism. The estimated fifty million people who visited the Chambre Syndicale would have seen a fashion hall divided into four units, each symbolizing the four seasons. In the words of Amy De La Haye: “Autumn was represented by the Longchamps races; the great hall of a luxurious private house evoked Winter; Spring featured a defile (fashion show); and Summer depicted the seaside resort of Deauville.”11 The couturiers drew lots for where they would exhibit. Jean Worth, who had drawn Fall and Summer, was tentative as to how sympathetic the themes would be to his more stately designs. His brother Gaston followed the allocated themes, while Jean thought better ...