![]()

The Guide

![]()

See the ‘Visiting Pompeii’ section at the start of this book for an overview of the recommended route to take while using this guide. Entry is via the Marine Gate.

To the left, and before entering the gate, are the remains of the Suburban Baths. To the right is the so-called Imperial Villa built against the city walls. The road to the gate is steep and would have been unsuitable for Roman wheeled traffic. There are two entrances through the gate; the one on the left was for pedestrians, the larger one on the right for pack animals. Both entrances could be closed off by double doors. The entrance to the Suburban Baths is on the left, through a low, iron gate and down some steps.

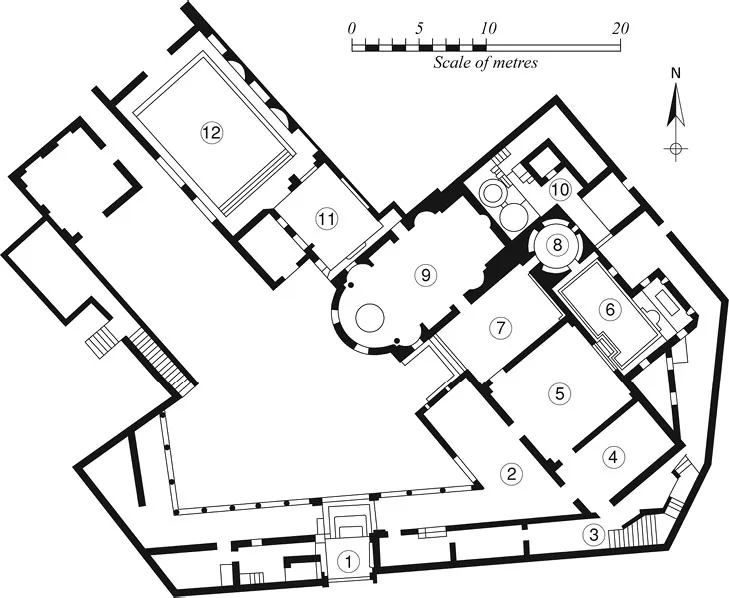

Suburban Baths (Figure 20)

The excavation of the Suburban Baths (21B) was finally finished in 1986, in the aftermath of the earthquake of 1980, by Fausto Zevi and Giuseppina Cerulli Ivelli. Dating from the early imperial period – possibly Tiberian – and although publicly owned, it seems to have been reserved for private clients.

August Mau records an inscription discovered in 1749, close to the Herculaneum gate, which advertised: THERMAE M CRASSI FRVGI AQVA MARINA ET BALN AQVA DVLCI IANVARIVS L – ‘the bathing house of Marcus Crassus Frugi. In charge (superintendent) the freedman Januarius’ (Mau, Pompeii: Its Life and Art, p. 400). Pliny the Elder wrote that M Licinius Crassus Frugi was consul in 64 AD and, put to death by Nero in 68 AD, owned a hot spring which gushed out of the sea at Pompeii (Pliny HN 31.5).

Figure 20: Plan of Suburban Baths

The baths are built on a single axis, almost north–south alignment, on a difficult triangular site, steeply sloped and located just to the north of the road leading to the Marine Gate. It may be the case that the baths were located just here to take advantage of the passing trade from a possible basin or canal for shipping, situated to the west of the baths.

The main entrance (1) is located to the north of the porticoed road leading uphill to the Marine Gate. This comprises a gated vestibule with a façade framed by two half columns; walk through and you are in a porticoed (2) triangular area paved with creamy white slabs of tufa stone. The entrance to the baths is on the right through the changing room (4), frescoed in the Fourth Style, with eight numbered erotic scenes on the upper part of one wall. We have entered a world of unbridled sexuality where various positions and pleasures are numbered, presumably so the male (or female) clientele could, if they wished, after their bath, retire upstairs to the three flats and enjoy from prostitutes ‘number 5 or number 7’. The staircase to this sexual heaven is located internally, in the south corner of the complex (3).

The scenes are half of the original number to have survived, and frescoed just beneath the erotic scenes are painted numbered cupboards, probably just like the remains of red cupboards that were found below by archaeologists.

From the changing room (apodyterium) we enter the cold room (5), with its cold plunge pool on the right (6). The changing room is floored with marble slabs, Fourth Style stucco, and the pilaster columns supported a corbel and a barrel-vaulted roof, whose ceiling is panelled with stucco reliefs, which include cherubs riding tritons, with others showing chariots drawn by billy goats. The chariots are filled with various objects, including cornucopias, thyrsus and theatrical masks.

The wall panels are framed by fluted pillars capped by an ovolo, an arched cornice with egg and dart decoration. The subject matter of the panels ranges from cherubs to flying storks.

Leading off from the cold room (frigidarium) is the cold plunge pool (6), with its walls frescoed with seascapes and Nilotic scenes. The pool (balneum) was filled by a cascade of water from a highly decorated nymphaeum, framed in a mosaic-covered alcove arch, with two columns holding up a mosaic-covered architrave topped by triangular pediments. The central wall mosaic in the niche portrays Mars and two cherubs holding his weapons.

The next room is the warm room (7) with its hypocaust heating of the floor and walls and in the corner of the room is a door to the sauna (8), with its four apses set into its wall. The circular laconicum was used for dry sweat baths. The circular shape is a standard design for this type of room – a small round space, where high heat could be produced (Vitruvius 5.10.5). The room is roofed with a masonry cone that springs just above the crown of the four apses set into its walls. The fresco decoration is blue on blue seascapes.

The next room to your left is the large apsed hot room (9) (caldarium), the floor heated by underfloor hot air from the adjacent furnaces (10) (praefurnium). The walls are also hollow with tegula mammatae tiles (tiles with dimples to enable a heated air space behind the frescoes), which are ornamented by seven niches and apses, which no doubt would have housed marble statues. The large apse, with its picture windows that overlooked the Bay of Naples, contained a circular marble basin (labrum) on a stucco-decorated brick pedestal. The cold water it contained would have enabled the bathers to cool themselves down or, if thrown on the floor, would have created copious amounts of steam.

Leaving the hot room one enters another heated antechamber (11), frescoed in the Fourth Style with stucco relief decorations, which leads on to a magnificent heated swimming pool (12) with tiers of marble steps leading down into the pool. The walls again are decorated with four niches, again no doubt to hold marble statues; the opposite wall has two large picture windows overlooking the Bay of Naples.

The baths are devoid of statues and furniture and it seems the bath-house was badly damaged in the earthquake of 62 AD and was still undergoing repair at the time of the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. After the eruption it seems salvage work by the Romans took place, which continued throughout the Middle Ages to modern times. Archaeologists have found both medieval and eighteenth-century pottery sherds in secure contexts and, although known about in the nineteenth century, it was not completely excavated until the excavation campaign of 1987–92.

Even in its sorry state, the magnificence of the decoration, the beauty of the rooms and the sheer thrill of stepping back into an almost complete, state-of-the-art first-century BC Roman bath-house is an experience not forgotten.

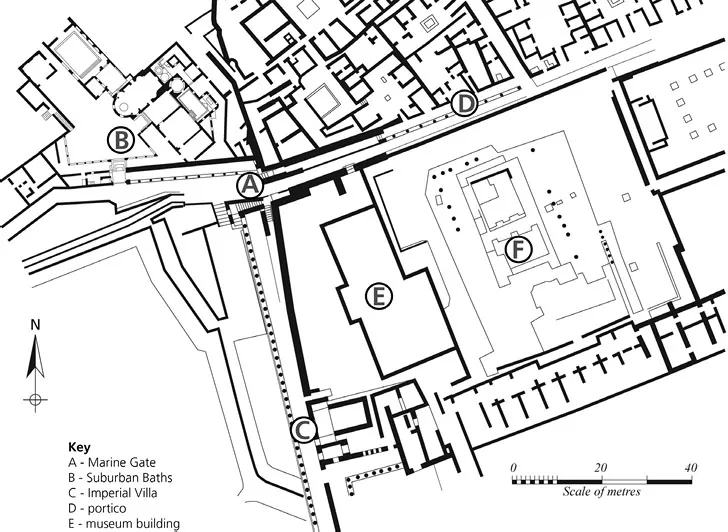

Imperial Villa / Marine Gate (Figure 21)

Leaving the bath-house, turn left and ascend the original Roman road, with its basalt rock surface, to the Marine Gate (21A). On your right you will see the imposing remains of the Imperial Villa (21C), built at the end of the first century BC against the city walls. A portico, supported by 41 fluted stucco columns, supported the roof and protected the rear wall of the portico, which was decorated in the Third Style with a black fresco background, framed by slender aedicules and embellished by figurative medallions and small ‘emblem’ paintings, most of which were removed by the eighteenth-century excavations. Midway along the portico, and its architectural focus, is an imposing structure, interpreted as a dining or entertainment room. The fresco decoration is in the Fourth Style and shows scenes from mythology, including Theseus slaying the Minotaur, Daedalus flying and Icarus, having fallen from the air, dead on the ground.

Figure 21: Plan of Marine Gate, Imperial Villa

We enter Pompeii by one of the original gates, now called the Marine Gate (21A). The road to the gate is too steep for carts and it is likely that goods and cargo from the nearby harbour would have been carried by mule or porter. The gate originally had two arches, one for pedestrians only, and was subsequently rebuilt as one entrance, with a barrel-vaulted roof in opus caementicium (mix of mortar and stone). Both entrances were closed with sets of double doors, as can be seen by marks left by the doors on the basalt rock road surface.

Once inside the town we pass shops on the left, which have a portico in front of them (21D), past the closed museum building (21E) on the right and enter on the right the terrace on which stands the remains of the Temple of Venus.

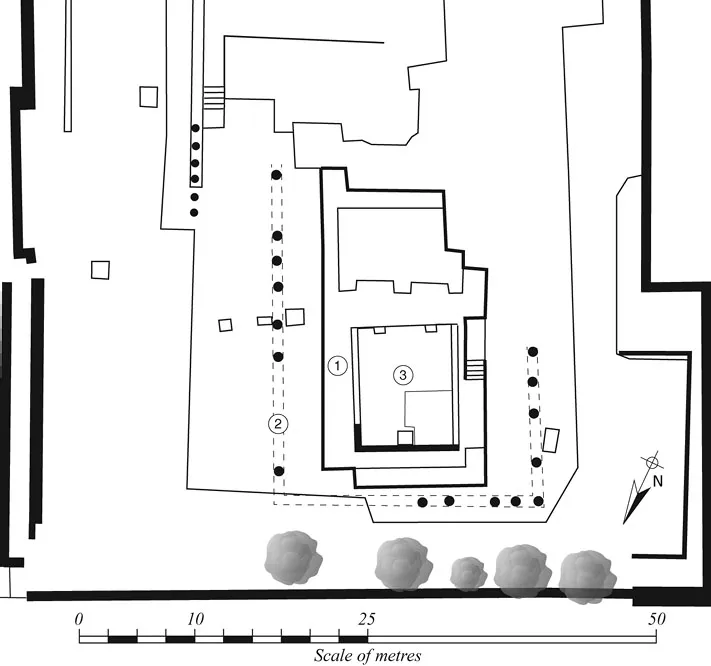

Temple of Venus (Figure 22)

You will note that the paving blocks of the Via Marina from the Forum to the precinct of the Temple of Venus (21F) are specked with bits of white limestone. This is not, as local guides will tell you, ‘to allow you to find your way in the dark’, but denotes a processional way from the Forum to the Temple of Venus.

Figure 22: Plan of Temple of Venus

The temple was built originally in the second quarter of the first century BC, probably by the dictator Sulla, who had laid siege to the city, conquered it, then installed his nephew Publius in charge of founding a colony of retired Roman veterans and renamed the city Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum. The cult of Venus Fisca, which predated the Roman conquest of the Samnite city of Pompeii, was continued in spirit, but the new temple was dedicated to Venus Pompeiana, the new patroness of the city. The temple was built in dazzling white Luna marble and, probably embellished with colour, it became a landmark at the entrance of the city from the harbour and the main approach road from the mouth of the River Sarno.

The temple was excavated by August Mau from 1898 to 1900, who postulated three building phases, the first being the original construction by Sulla in 80 BC, when the area was cleared of buildings, presumably houses and shops and a temple in a sacred precinct with colonnades. The second phase was a partial rebuild at the time of Claudius and this work had not been completed by the time of the earthquake of 62 AD. The third phase was post-earthquake, when the debris was cleared away and rebuilding started, only to be halted by the eruption of 79 AD.

Today, enough remains to be able to reconstruct it by survey. The temple sat on a podium (1) with the frontage probably of the Corinthian order, facing south. The temple stood in the centre of the site and was porticoed on three sides (2). The south side is left open to view for miles around.

The temple itself was prostyle, with a deep pronaos preceded by a staircase across the front façade. It is likely that there were six Corinthian columns across the front of the pronaos, with four down each side.

The cella was square (3), with a single entrance with a door, and against the back wall stood the base for the statue of Venus.

The temple, built of white Luna marble with columns in the same material – of which one has been re-erected, but not in its correct location – was one of the finest monuments in the city.

Unfortunately, after the eruption of 79 AD the temple could still be seen and was pillaged by the surviving Romans for its marble and statues. However, enough survives to enable you to imagine the effect this great temple would have had on the surrounding countryside and its people.

Temple of Apollo (Figure 23)

Retrace your steps, and further ahead on your left is the Temple of Apollo (24B) situated in an area enclosed by a portico of 48 columns (1). The cella (2) or shrine sits on a high podium (3) surrounded by a Corinthian colonnade (4), with six columns to the front. The earliest building on the site dates from 575–550 BC. Two bronze statues flank the façade of the temple; Apollo to the right (5) and a bust of Diana to the left (6), both deities portrayed as archers. The temple’s altar (7) is situated in front of the staircase (8) leading up to the temple and on the left the column with the sundial was added in the time of Augustus (9).

The cult of Apollo was the most prestigious in pre-Roman Pompeii and occupied the most important spot in the town. The earlier temple was constructed of wood and embellished with terracotta panels, fragments of which were retrieved by archaeologists from trenches inside the temple area. Opinion is divided about whether this first building indicates that the early town was of Greek or Etruscan origin, as items from both cultures have been found on the site.

The site was reorganised and the area reduced in the second century BC, when the adjacent Forum and public buildings were built, but even then the cult ...