![]() PART 1

PART 1

THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR![]()

1

ESPIONAGE AND THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR

There is one evil I dread, and that is their spies.

GEORGE WASHINGTON, March 24, 1776.

Quoted by US Central Intelligence Agency, Intelligence.

Espionage played a crucial role in the turbulent conflicts of eighteenth-century Europe, where ruthlessly ambitious monarchs clashed over trade, territory, and religious differences. Among European nations, Great Britain had few rivals in espionage, and it had developed an effective intelligence service two centuries earlier under Francis Walsingham, Queen Elizabeth I’s spymaster. By the mid-1700s, Walsingham’s successors had seeded spies inside the royal courts of Britain’s European neighbors to protect its empire, which had become the major economic and military power on the globe.

Before the Revolution, the British were too preoccupied with threats from European rivals to spy on their American colonies and had little need to do so. The relationship between the Crown and its subjects across the Atlantic was mutually beneficial for both sides. The British were content to let the colonies govern themselves as long as trade flourished and the Crown benefited. The colonies purchased half the ironware, cotton, and linen produced in Britain, which in turn was the major consumer of raw materials from its New World subjects. From 1700 until the Revolutionary War, colonial exports to Britain grew sevenfold, and trade between the colonies and the mother country increased from £500,000 to £2.8 million.1

The British economy, however, began to suffer from the heavy costs of defeating France in the Seven Years’ War (1756–63). To recover their losses, King George III and his Parliament imposed a series of taxes on the colonies. Tensions between the Crown and its subjects escalated from protest to covert resistance and finally erupted into armed conflict in Massachusetts, the hotbed of colonial opposition to the taxes. Britain’s stubborn refusal to compromise and its rejection of appeals for negotiations only drove the colonists further along the road to revolution.

Despite British intransigence, colonial support for independence was hardly unanimous even after the harsh taxes were imposed. Even the most vocal opponents of the king’s taxes, including founding fathers like John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, initially opposed independence and simply sought a colonial voice in Parliament regarding any decisions to tax the colonies.

Even after the first salvos of the war in Lexington and Concord in 1775, the Second Continental Congress advocated negotiations to reconcile with London. The assemblies of two colonies, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, instructed their delegates to Congress to oppose any move to secede from the British Empire. As John Adams later claimed, before the war one-third of the colonial population supported independence, one-third opposed it, and the remaining one-third was neutral.2

These divided loyalties facilitated espionage by both sides. Recruiting spies was a relatively simple task because the colonists, whether Tory or revolutionary, spoke the same language and shared the same heritage. Espionage swiftly became as important to the British in the colonies as it was in the royal courts of Europe. To suppress the independence movement, the British relied on spies to gauge levels of colonial unrest, troop strength, and stockpiles of munitions and supplies. The Crown spared little expense to fund this espionage effort. Within a few years after the first shots of the American Revolution were fired, the budget of British intelligence chief William Eden doubled.3

Espionage was even more important to the Revolutionary cause. The colonials faced a better-armed and more experienced enemy, and colonial commander in chief George Washington realized that intelligence on British troop strengths and movements could even the odds. As the intelligence historian Thomas Powers notes, espionage played a central role in the American Revolution: “The American cause was born in secrecy in the coffeehouses of Boston, it was nurtured in secrecy in the Committees of Correspondence, it was pressed by citizens disguised as Indians who dumped tea in Boston harbor. … Behind the pageant lay all the hidden web of espionage, propaganda, secret diplomacy. In truth, it was the clandestine arts as much as American armies which won American independence.”4

Espionage, in fact, was the spark that ignited the war. General Thomas Gage, the royal governor of Massachusetts and commander of British forces, received a report from a spy that New England colonists were hiding stockpiles of weapons because they feared the British would seize them.5 Gage decided to march into Concord to capture the weapons before the colonists could use them against his troops. On the revolutionary side, Boston patriots learned of Gage’s plan of attack from their own spies in the king’s ranks. Paul Revere, chief of Boston’s amateur intelligence service, alerted two leading figures of the local resistance, John Hancock and Samuel Adams, that Gage intended to arrest them. Revere’s renowned “Midnight Ride” to warn these two founding fathers was perhaps the first delivery of timely threat information to key policymakers by American intelligence.

Revere, a silversmith by trade, was chosen by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress to conduct intelligence activities as part of the establishment of the Committee of Safety to protect the colony. He assembled a band of about thirty amateur spies who were dubbed the Mechanics because, like Revere, they were all artisans.6 Their professions gave them natural pretexts to move about Boston and spy on Gage’s troops. They often acquired useful information in alehouses by eavesdropping on British soldiers who talked indiscreetly after quaffing a few brews.7

The Mechanics also tried to ferret out British spies among Boston’s Tory citizens but found the task more difficult than collecting intelligence. The shared language and heritage that facilitated espionage complicated the discovery of spies. The average colonist strolling about the town square in his waistcoat, ruffled sleeves, and distinctive tricornered hat or quaffing ale in the local tavern could be a Tory or a patriot. Distinguishing one from another was even difficult within families: Benjamin Franklin’s son William was an ardent loyalist and the Crown’s governor of New Jersey. He spied on his father and reported on his activities to the British. William was later imprisoned by the Continental Congress and, after his release, organized raids against revolutionary forces in New York.8

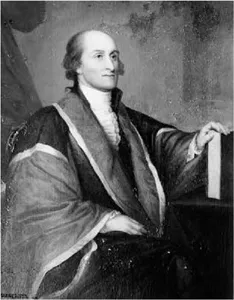

Because of the blurred lines between Tory and patriot, George Washington left counterespionage to individual colonies and local commanders who would be better equipped to identify spies among their townsfolk.9 As a result, although Washington may have dreaded British spies, he never established a central counterespionage unit to thwart British espionage. However, he did play a role in establishing a fledgling counterspy service in one of the colonies. New York, unlike Massachusetts, was heavily populated by Tories and was occupied by British forces in 1776. In June 1776 Washington convinced the New York Congress to establish the Committee on Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies (CDDC) to “close the regular channels of intelligence from the city.”10 He chose John Jay, who would later become the first chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, to head the CDDC, which in effect became the nation’s first counterespionage service. Because of Jay’s work on the CDDC, in 1997 the US Central Intelligence Agency honored him as the father of American counterintelligence.11

Jay was the first in a long line of American spy hunters with a penchant for absolute secrecy. He often disagreed with Washington’s desire to publicize some intelligence successes for morale-building purposes.12 Even after the war, Jay related to his close friend, James Fenimore Cooper, the exploits of his master spy in the CDDC but refused to provide his agent’s name. Based on Jay’s tales, Cooper wrote The Spy, a novel in which the hero, Harvey Birch, spies on the British for George Washington.

The character of Birch was largely based on Enoch Crosby, a shoemaker from Danbury, Connecticut, who left the Continental Army because of war injuries but later reenlisted in New York. Crosby befriended a British sympathizer in Westchester County, New York, who, believing that the shoemaker shared his views, introduced him to a Tory spy ring. After exposing the ring to the CDDC, Crosby rejoined his new Tory comrades in time to be arrested with them and then engineered his own escape. Jay was so impressed with this operation that he recruited Crosby as a permanent counterspy and provided him with the hefty budget of one horse and $30 for the task.13

PAINTING OF JOHN JAY by Gilbert Stuart. Library of Congress

Crosby was a master in eliciting information and winning the trust of Tory spies, who were duped by his humble demeanor. He was, after all, a mere shoemaker, wandering from town to town to eke out a living by cobbling shoes. He was the quintessential little gray man, shy, taciturn, only 5 feet, 3 inches tall, which was slight even by eighteenth-century standards. To protect his cover, he was often arrested along with the spies he exposed but repeatedly escaped. On one occasion he was taken prisoner and brought to Jay’s house. Fortunately, a witting house servant recognized Crosby and treated his guards with enough whiskey to put them to sleep and enable him to slip away and rejoin his British confederates.

Crosby’s cumulative counterespionage achievements were significant, but he and his colleagues in the CDDC never exposed any major British spies. As the intelligence historian John Bakeless noted, “No amount of counterintelligence could catch all the British agents” operating in the colonies.14 Among them were three highly placed agents in the inner councils of the American cause whose spying could have altered the course of the Revolution.

![]()

2

THE FIRST SPY

BENJAMIN CHURCH

In the Fall of 1774 and Winter of 1775, I was one of upwards of thirty, chiefly mechanics, who formed ourselves into a Committee for the purpose of watching the Movements of the British soldiers, and gaining every intelligence of the Movements of the Tories. We held our meetings at the Green Dragon Tavern. We were so careful that our meetings should be kept secret that every time we met, every person swore on a Bible, that they would not discover any of our transactions, but to Messrs. Hancock, Adams, Doctors Warren, Church, and one or two more.

PAUL REVERE, letter

More than 230 years have passed since the American Revolution, and Benedict Arnold still towers over all other spies against America as the most infamous traitor in US history. Arnold, however, was not the first major spy against America. That dubious honor belongs to Dr. Benjamin Church. Although Church remains an obscure figure in the history of the Revolutionary War, he was the most highly placed civilian spy in the British espionage network. Because he was trusted with the most important secrets of the colonies, he could have inflicted significant damage on the revolutionary cause.

Church was among the leading patriots in the highly patriotic colony of Massachusetts. In December 1773 he participated in the Boston Tea Party, when colonists disguised as Indians dumped chests of tea on a British ship overboard to protest the king’s tax. Church was also a propagandist who penned several pamphlets supporting the revolutionary cause. He was elected to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and was chosen by his peers to present the colony’s defense plans to the Second Continental Congress and seek aid for the colony’s militia.1

A physician by profession, Church treated wounded revolutionaries at the Battle of Bunker Hill and was eventually appointed chief surgeon of the Continental Army. As Paul Revere’s comments indicate, Church was also in the inner council of Boston revolutionaries who swore on a Bible at the Green Dragon Tavern to protect the colonists’ most guarded secrets. His revolutionary credentials were impeccable.

Church was also a highly paid spy in the espionage network of the British general Thomas Gage. Gage needed intelligence on the plans, intentions, and capabilities of the upstart Massachusetts revolutionaries. After the Boston Tea Party, King George III decided to crack down on the mutinous colony. He appointed Gage commander of British Forces in North America and royal governor of Massachusetts to quell the increasing defiance of his colonists. Soon after his arrival, Gage began to satisfy the monarch’s wishes by closing Boston Harbor to ships from overseas and other colonies, effectively cutting Massachusetts’ economic lifeline. He also restricted many of the self-governing authorities of the colony and reduced the jurisdiction of its courts. Gage realized that colonial opposition to his harsh measures was quickly mounting, so he infiltrated spies to discover Massachusetts’ progress in building a militia and stockpiling weapons and supplies.

Paul Revere was convinced that one of Gage’s spies had penetrated the Sons of Liberty, an underground organization of colonists dedicated to subverting royalist rule in America. One of Revere’s informants told him that Gage knew details of a secret Sons of Liberty meeting held in the Green Dragon Tavern the day after it occurred.2 Church, however, was beyond reproach, despite hints of some suspicious activities. In one instance, Revere was advised that Church had been spotted entering Gage’s quarters in Boston and appeared “more like a man that was acquainted than a prisoner.”3 Church later claimed that he had been detained but set free in a few days. Revere dismissed the incident.

Revere was not alone in ignoring disturbing signs about his Sons of Liberty colleague. Church was married but had taken a mistress and begun living a lavish lifestyle, although his colleagues were aware that he had been in dire financial straits. He was living well beyond his means as a physician, a profession that hardly netted the income modern doctors command (his salary as surgeon general was $4 a day, which was relatively small compensation for a physician of that stature even by eighteenth-century standards).4 Despite this unexplained wealth, the notion of a dedicated revolutionary like Church spying for the enemy was simply inconceivable and foreshadowed the endemic blindness of Americans to glaring indicators of espionage throughout American history. Church was only the first of many Americans who committed espionage out of greed and whose newfound riches were ignored by colleagues and counterspies.

BENJAMIN CHURCH was a prominent and trusted patriot in Massachusetts during the Revolution, but he turned out to be a spy for Britain. National Guard Bureau, Army Heritage Education Center

Church’s espionage might never have been detected if he had not made a serious tradecraft blunder in communicating with the British. Communications is the riskiest element of espionage. At some point, the spy and his handler must communicate for one to receive information and for the other to receive his espionage tasks and money. As former Central Intelligence Agency director Allen Dulles noted, “there is no single field of intelligence work in which the accidental mishap is more frequent or more frustrating than in communications.”5 In Church’s case the mishap proved to be his undoing.

Church’s greed led to the tradecraft blunder. Church had been dispatched to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia and was thus out of contact with Gage. Meanwhile, he received a letter from his Tory brother-in-law pleading with him to renounce his rebellion against Britain. His brother-in-law asked him to respond via a British naval commander in Newport named Captain James Wallace. Church may have suspected that the letter was a veiled attempt by the British to renew contact with him, so he wrote a letter i...