![]()

1

BRAZILIAN

Language

That’s a Lot of Portuguese!

Perhaps there is no more central issue for intercultural communication than the choice of language. Even in situations where two parties are totally bilingual, a decision will still need to be made about which language is going to be used. In most situations, at some level, someone needs to make a concession to use a language in which he or she is less fluent. In other situations when even this partial fluency is absent, we are forced to resort to interpreters and translators. So it is appropriate that we begin by looking at language. It is inevitable that the use of one’s native language or the use of a local language will drastically affect intercultural communication.

In this chapter we give a brief introduction to the use and role of Portuguese in Brazil, and a short description of the use of English as a lingua franca. We then look at a number of examples to see how English loanwords are used in Brazil. The chapter ends with a few recommendations for how to deal with language differences between native speakers of English and Portuguese.

WHO SPEAKS PORTUGUESE?

When we look at Brazil and consider how language becomes an issue of intercultural communication, the first thing we note is that Brazil is the only country in Latin America where Portuguese is the official language of the people. This is not an insignificant feature. Portuguese is the seventh most common language in the world. Only Mandarin, English, Spanish, Hindi-Urdu, Arabic, and Bengali have more speakers than Portuguese. There are more speakers of Portuguese than there are of Russian, Japanese, German, French, Korean, and Italian, just to name a few. Unfortunately, many uninformed people simply assume that Brazil is a Spanish-speaking country—which, by the way, drives Brazilians crazy.

According to statistics from the US Central Intelligence Agency’s World Factbook, Brazil’s population of 201 million represents more than half the population of South America.1 No other country even comes close. The second-most-populated country in South America is Colombia, which at 45.7 million has less than a quarter of Brazil’s population. Even when we compare South America with North America, Brazil has almost twice the population of Mexico (116 million) and more than five and a half times the population of Canada (34.7 million).

Brazil is the only Portuguese-speaking country in Latin America, in part because of a semi-unexpected result of the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas. At that time, to resolve land disputes between the world powers Spain and Portugal, a line was drawn along the meridian that was about 370 leagues west of Cape Verde in West Africa. This was designed to give the lands west of that line to Spain (mainly the Americas) and those east of that line to Portugal (mainly Africa and the coasts toward India). It turns out, however, that part of Brazil actually extends farther east than what people had supposed. As a result, Portugal claimed part of “their” land in the Americas, when Pedro Álvares Cabral landed in Brazil in 1500. Five hundred years later, the result is that Brazil, with its historical roots in Portugal, is now the only Portuguese-speaking country in the Americas.

WHAT MAKES PORTUGUESE, PORTUGUESE

Portuguese is a Latin-based language, and thus it is similar, at least to some degree, to the other so-called Romance languages (e.g., Catalan, French, Italian, Romanian, and Spanish). This similarity is especially important in the case of Spanish, because Brazil is almost completely surrounded by Spanish-speaking countries. In fact, native speakers of Portuguese almost automatically understand quite a bit of Spanish. The inverse is less true, however. Native speakers of Spanish may get the gist of basic Portuguese, but they actually understand it much less than the other way around. This leads at times to perceived slights, for some Brazilians seem to feel that Spanish speakers are intentionally unwilling to understand what is being said. Brazilians who are more acquainted with their Spanish-speaking counterparts, however, recognize this for what it is: Comprehension is more difficult going from Spanish to Portuguese than vice versa.

To give a brief example, let us look at the words for various body parts and the numbers from one to ten in Spanish and Portuguese:

Portuguese: cabeça, braço, perna, pé, mão, olhos, nariz, boca, orelhas

Spanish: cabeza, brazo, pierna, pie, mano, ojos, nariz, boca, orejas

Portuguese: um, dois, três, quarto, cinco, seis, sete, oito, nove, dez

Spanish: uno, dos, tres, cuatro, cinco, seis, siete, ocho, nueve, diez

We see that many of the words look similar. However, in actual speech, many of the Portuguese words are shorter than their Spanish equivalents. And Portuguese has many more contractions than Spanish. As a result, when hearing Spanish, Portuguese speakers catch most everything that is said; but when hearing Portuguese, Spanish speakers seem to feel that something is missing. Here is a simple example to illustrate this concept:

Portuguese: No livro da escola tem a foto da lua.

Spanish: En el libro de la escuela, tiene la foto de la luna.

English: In the book from the school, there is a picture of the moon.

Indeed, the Portuguese words are shorter, and there are more contractions. Imagine being a speaker of Spanish who hears da lua for de la luna (of the moon). It just sounds like parts are missing. Conversely, a Brazilian who is used to hearing da lua gets additional parts when hearing the Spanish de la luna.

WHAT BRAZILIANS THINK OF NONNATIVE PORTUGUESE SPEAKERS

When a person goes to Brazil to work professionally, the Brazilians will not necessarily expect that person to speak Portuguese, but they will be pleasantly surprised if he or she does. At the same time, it is becoming more common to find foreigners who do speak Portuguese. Additionally, and not ideally, as long as you do not suppose that Spanish is the language of Brazil, Brazilians are also open to communicating with foreigners with a little mix of English, Portuguese, and Spanish.

Brazilians are quite receptive to people who try to speak Portuguese, even if they speak the language poorly. This type of response is not a given. For example, in the United States, in general terms, people are simply assumed to speak English. If foreigners do not speak English well enough to be readily understood, many Americans become frustrated and give up trying to communicate at all, sometimes even equating an inability to speak English with a lack of intelligence. This is not the case in Brazil. Someone who does not speak Portuguese well is viewed simply as someone who lacks skill in the language. It is not a given that every foreigner will speak Portuguese.

Some countries tend to emphasize more than others the need to speak a language correctly in terms of grammar. For example, much of French identity is wrapped up in the French language. Although most French businesspeople will tolerate the usage of grammatically weak French, there is a stronger resistance to this than, say, the usage of grammatically weak French in Quebec or grammatically weak English in the United States. Brazilians tend to fall into the category of accepting limited control of Portuguese more readily.

Additionally, speaking Portuguese imbues the foreigner who is trying to use the language with an added benefit. Brazil may be the language of more than 200 million people, but it is not a widespread second language. In fact, only an estimated 30 million people speak Portuguese as a non–mother tongue. By contrast, among the 338 million speakers of French, only 80 million or so speak it as a mother tongue; and of the 1.5 billion people who speak English, only 330 million or so speak it as their first language. Moreover, of the 220 million people who call Portuguese their mother tongue, more than 90 percent live in Brazil. As a result, when someone chooses to learn Portuguese, most Brazilians presume that this is because he or she has a sincere interest in Brazil, and that led to his or her decision to study Portuguese in the first place. This is seen as a compliment, and is likely to predispose Brazilians favorably to the foreigner who is speaking (or even just trying to speak) Portuguese.

BRAZIL AND THE PORTUGUESE-SPEAKING WORLD

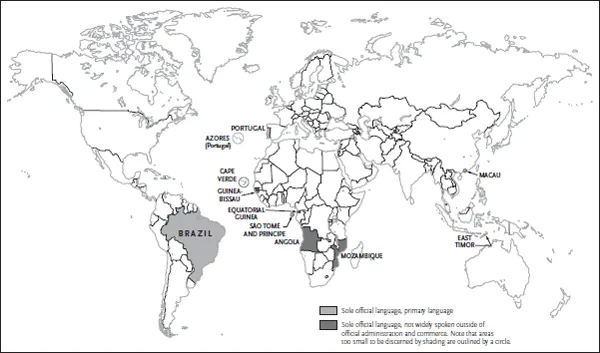

As the world’s largest Portuguese-speaking nation in both population and economic terms, Brazil has a somewhat special relationship with other Portuguese-speaking nations. There are nine nations where Portuguese is the official language: Brazil, Angola, Cape Verde, East Timor, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Portugal, and São Tomé and Príncipe (figure 1.1).

In 1996 Brazil and six others among these nations (East Timor and Equatorial Guinea joined later) formed the Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa, specifically to further political, cultural, and economic cooperation among fellow Portuguese-speaking countries. Because Brazil dominates these other countries in size and economic clout, the result has been much stronger trade ties with these countries, especially those in Africa. Currently, Brazil’s third-largest African trade partner is Angola, and its fourth-largest is Mozambique. Brazil also enjoys a number of political and cultural exchanges with its African neighbors. In chapter 3 we expand on this situation a bit further.

Figure 1.1

The Portuguese-Speaking World

HOW MUCH ENGLISH IS USED IN BRAZIL?

It is undeniably true that worldwide, in many ways, English is the lingua franca for professional activities. It is also true that many Brazilians do speak at least some English. And it is also the case that if you are only dealing with highly educated, high-level upper management, perhaps you will find yourself being able to use English in Brazil. However, the use of English in Brazil breaks down quickly. If a person plans on dealing with suppliers, factory workers, local civic leaders, secretaries, and just about any other sector, expect your ability to use English to be more limited.

For example, if a foreign visitor goes to major museums, historical sites, or other typical tourist locations abroad, it is quite common to see English translations on many of the written descriptions. This is less common in Brazil. When going to restaurants abroad, one frequently sees English translations of the menus. This is less common in Brazil. When travelers go to hotels, take a taxi, or use public transportation services like a subway, in many countries there will be a fairly strong presence of English-language options. This is less co...