![]()

PART ONE

CONSTITUTIONAL

PULSE DIAGNOSIS

![]()

CHAPTER 1

CONSTITUTION AND CONDITION

Regardless of the therapeutic modality employed, all treatment can be thought of as primarily concerned with either the manifested condition (symptoms, diseases, syndromes, etc.) or with the original energetic disturbance that allowed the current presentation to develop. There are several technical terms that describe this distinction, roots and branches being the one most commonly employed in Oriental medicine. It provides a fitting image: If the branches or leaves on a tree are attacked by some injurious factor, a gardener may apply localized treatments, even to the extent of pruning them, in order to allow a new round of growth from the presumably healthy roots to occur, and all will be well. On the other hand, if the very roots are attacked, even if the leaves and branches continue to appear healthy for a while, the tree itself may be doomed unless the roots can be restored to a healthy state, so the best gardeners will never disregard the health of the roots, whether or not there are problems showing up in the branches or leaves. Traditionally, this line of thought can be taken a step further: If the roots are maintained in perfect health, then the branches and leaves will be supplied with the optimal requirements to withstand many an injurious factor, and there are those who claim that a well guarded root will lead to a state of immunity to illness. This is an example of the hierarchical nature of many of the relationships in living beings: The roots can be thought of as more significant than the branches, which are relatively more expendable. Thus it may seem counter-intuitive that the roots are usually unseen (hidden in the ground for most plants), while the branches are easily observed, and where any abnormality may be readily detected. Human beings are not really different from trees in this regard: What is easily seen as an abnormality or symptom may be much less crucial to the survival of the individual than the unseen phenomena (the root imbalance) which may ultimately determine their fate. For didactic purposes I have presented the notion of roots and branches as separable aspects of a living organism, but this is not really the case. In fact, there is a constant interplay, back and forth, between the roots and branches, in both plants and people, as in all living beings. Thus it is not necessarily true that simply treating a diseased branch will fail to cure an illness, even if there are less than perfectly healthy roots. The branches are always sending influences back to the roots, and, in some circumstances, the beneficial influences that treated branches can now send back to the roots may be enough to also heal the roots. For this reason, I believe it is wrong to dismiss symptomatic treatment as insufficient at best, and outright harmful at worst. Each situation needs to be evaluated on its own merits. At the same time it would be a capital mistake to forget the natural hierarchy between roots and branches. When in doubt, take care of the roots.

We live in a world of multiple medical systems whose variants occur in both the spatial and temporal realms. It is common to contrast modern Western medicine with traditional Oriental medicine, for example. In tracing each of these lineages backwards in time, we come across the curious finding that distinguishing East and West may not be so simple. How are we to classify ancient Greece? Was it East or West? Hippocrates (see Figure 1.1) is known as the “Father of Western medicine,” but in fact both his notions and those of Galen, who followed in his footsteps, are in many ways closer to those of Oriental medicine, being based on Humoral and Elemental theories of balance. I make this observation for several reasons, the first of which is to introduce the topic of constitutional theories, the Hellenic (Greek) Four Temperaments (Sanguine, Phlegmatic, Choleric, and Melancholic) being perhaps the most well-known example of constitutional types with which the Western reader might be familiar (see Figure 1.2). The second reason for starting with ancient Hellenic (Greek) thought is to shine a light on the obvious similarities between it and the traditional medical systems known as Unnani (Arabic/Persian), Ayurveda (Indian), and that of China. In Footsteps, I made the claim that the various versions of Oriental medicine I surveyed were all branches off a common trunk of shared beliefs. When I finished that book in 1996, I had not yet realized that this common trunk also includes Hellenic, Unnani, and Ayurvedic medicine, and this subsequent realization was crucial to my current understanding of both constitutions and conditions. I should point out that the concepts of Humors and Elements can be applied to either a root or a branch, and likewise to one’s constitution or one’s condition. It is always imperative to specify how these terms are being applied in each case.

Figure 1.1 Hippocrates, exemplar of Eastern or Western medicine?

Figure 1.2 The Four Temperaments: Phlegmatic, Sanguine, Choleric, and Melancholic

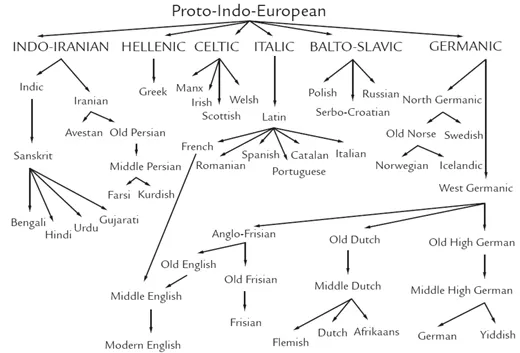

Returning to the question of shared beliefs between the various styles of Oriental medicine, is there any historical data to substantiate an interrelationship between Hellenic, Unnani, Ayurvedic, and Chinese medicine? Both Chinese and Indian medical ideas have an oral tradition that probably predates any written record. Much Chinese medical lore is attributed to the Yellow Emperor, Huang Di (c. 2700 BCE), and there are corresponding fables concerning the origins of Ayurveda during the Neolithic and Bronze Age (c. 2300 BCE) along the Indus River in northwest India. The orthodox belief is that the four Vedas, or canons of wisdom, were originally revealed by the godhead, Brahma, creator of the universe, to a succession of divine entities including the god Indra, who passed this knowledge on until it was finally heard by a group of inspired sages, the Rishis, who in turn continued the teachings via an oral tradition maintained by the Brahmin or priestly caste. It was from this Vedic (Hindu) tradition that the Buddha (c. 563–483 BCE) initiated a new spiritual system, one that was as closely intertwined with Ayurvedic medical teachings as was its Hindu progenitor. Buddhism was much more widely disseminated than was Hinduism, and had a major impact on Chinese thought in all areas, including medicine. While the classics of Chinese medicine (Neijing, Nanjing, Shanghanlun, Maijing) were first written between 200 BCE and 200 CE, those of Indian medicine (Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita) were more likely written between 760 and 660 BCE, and thus possibly represent an earlier stratum of medical thought. These early texts already discuss the Humoral and Elemental theories that are to be found in most versions of Oriental medicine. Since there was undoubtedly a long period of oral transmission of these ideas prior to their being written down, it is impossible to know which is earliest. The question then becomes, was there any contact between these cultures prior to their first written texts? Certainly there are scholars who would answer in the affirmative. For example, the Chinese Yueh-chih tribes, the Kushans, coming from western China, occupied Benares (Varanisi) in northeast India. They are considered to have formed a bridge, the Silk Road, between East and West. This trade route between the Mediterranean Sea and China was operative prior to 500 BCE, although it did not receive its name, or heavy traffic, until much later. Likewise, the Burma Road (c. 115 BCE) to the south also opened the exchange of material goods and ideas to and from China. There is no doubt of early contacts between Persia and Greece (c. 550 BCE, along the Silk Road) as related by the Greek historian Herodotus, and as both the Persians and the Vedic peoples in India were from the same Aryan stock, the likelihood that all these cultures exchanged ideas in the period prior to the writing down of medical texts seems inescapable.

Figure 1.3 Indo-European language tree

One final aspect of the attempt to reconstruct ancient medical history is worth mentioning. In almost every country of the ancient world, the great repositories of learning were destroyed, frequently by fires, from China (which supposedly spared medical texts), to the great library in Alexandria, whose destruction was begun by Caesar in 47 BCE and probably completed by the Muslims who captured this Egyptian city c. 64...