![]()

Part I

What God Forgot to Tell Surgeons

![]()

1

Genesis

In the beginning was a cell, a fusion of sperm and egg, Yang into Yin. Individually they were nothing, but combined they could conquer the world.

This was you, your cell… Maybe, deep inside you, it still exists?

The story of how that cell became you is the most amazing story ever told. It is a story that has not only created the astronomical complexity of our brains and the virility of our hearts, but is also responsible for civilisations and art, love won and life lost.

The cell contains everything within it to produce this, and yet it is invisible. How did it do this? You may think you know the answer in genetics, but you only have half the story.

The genes are like a great library, but a great library needs organisation. The story of this organisation is also the story of Acupuncture, explaining how the body creates and maintains order out of chaos. For the story of Acupuncture is the story of life itself, and it is only now, as modern medicine unravels the interactions between cells, that we understand what the ancient Chinese physicians knew: that the space between the cells is as important as the cells themselves.

![]()

2

The Single-Cell Universe

When your cell first starts it is in a world of space: a cellular being floating in the primordial soup of the fallopian tubes. It has just emerged from its own Big Bang: the moment of fusion of sperm and egg that has created your universe. It knows no up, no down, and it has no reference to right and left, back or front, for it has no need. As a single cell it is required only to survive in its dark space.

Soon it divides. Then these two cells divide again, and again, and again, until it is a ball of cells, a morula (Latin for the mulberry fruit it resembles), and an awareness is beginning within the cells that there is a spatial relationship with other cells. There is the embryogenesis of organisation. Within a few days the outer and inner cells of the morula start differentiating. They are performing individual roles. They are specialising.

The cells are responding to their relative positions by subtly altering their function. Those in the centre begin to secrete fluids. An egg is forming and the inside of this egg is even named the Yolk Sac. Those cells on the outside become stronger, tougher, more like skin.

The process continues at an astonishing rate. Within a week there are thousands of cells. Now the ball of cells is tumbling down the walls of the womb. It grabs a place to hold on and burrows into the endometrium – the surface of the womb. The ball of cells now has not only an inside and outside but also a left and right, up and down, near and far.

The parts on the outside start forming the placenta; the inside divides and creates the embryo. The cells decide that one end will become the head, the other the tail. The primitive spinal cord appears, and one end becomes bulbous, the primitive brain. Cells stream off from the other side and form organs and muscles. Tissues fold over themselves, bend and rotate, move from one end to the other. It should be chaos, but instead it is poetry in motion.

The result is a perfectly formed mass of ten trillion cells. That’s ten thousand, thousand, thousand, thousand cells!

Each cell knows not only where it is but also what it should be doing and which cell it should be next to. They have formed structures of immense complexity: an upside-down gossamer-leaved tree of a lung, a million nano-filtration units in the kidney, and a brain that can organise life into human civilisation – and they have done all of this from one invisible cell.

All of this is possible because of those 23 double-stranded spirals of DNA, and an epic level of organisation. When cells lose this organisation, then what happens is called disease.

The nastiest, the most feared and the most incurable of all diseases is cancer. Cancer is called cancer because it is the Latin word for, and acts like, a crab, spreading outwards with its malignant claws. This is the defining aspect of cancer: its uncontrolled spread. These are cells that no longer know their position and role in the body. They have lost their connection to the body. They are no longer part of it; they have become the enemy of the body.

To understand how our cells stay connected, and why when we lose this we develop cancer, we have to look at the most ignored tissue in the body: fascia.

![]()

3

‘A Name but no Form’

NANJING, ISSUE 38, 1ST CENTURY AD

Cancer spreads through fascia (see Appendix 1) yet, despite this, fascia is the great ignored substance of Western medicine.

Wikipedia merits fascia (pronounced ‘fa-sha’) with a mere 18 lines; textbooks of medicine ignore it completely,1, 2 and its only contribution to Western medicine is that it sometimes gets inflamed (fasciitis) and it sometimes throttles parts of the body (compartment syndrome).

Despite this, every good surgeon respects fascia. Every nerve, muscle, blood vessel, organ, bone and tendon is covered in it, and it tells a surgeon where things should be. Fascia isn’t there just to help surgeons; it is there to enable the body to know where things should be and what they should be doing.

Surgeons make good use of this biological ordering, though. So long as they stay in the plane of the fascia they will cause little damage. Minimally invasive (keyhole) surgery exists thanks to this exact property. It exploits the fascial envelopes to create large internal spaces for performing operations, such as laparoscopies: it is possible to put a camera into the abdomen, have a look around your liver, your guts, your private parts (if you’re a woman) and leave without causing more than mild discomfort. In fact, this is so easy that sometimes doctors do it just to have a look. (Doctors, like most intelligent people, are curious and nosey creatures and can almost always justify having a look around.) This is all possible because of fascia and the compartments it makes in the body.

Even the simplest operation will focus on finding the fascial planes and then working around them: Langer’s lines of the skin tell surgeons how the collagen in the skin is arranged and surgeons then cut along these to minimise scarring.

Chinese medicine, however, respects fascia as much as, if not more than, any surgeon. It devotes not one, but two, organs to this most universal of tissues: the Pericardium and the Triple Burner. However, Western medicine disputes that these organs exist.

Chinese and Western medicine can seem contradictory and confusing at times (see Appendix 2) but at least they agree on the existence of all the organs…with the exception of these two. The pericardium is seen as an inert fibrous sac in Western medicine, hardly what would constitute an ‘organ’, and the Triple Burner exists neither as a physical organ nor even a concept. However, neither does it appear to exist as a physical organ in Chinese medicine! In the 2000-year-old medical classic the NanJing (The Classic of Difficulties), the Triple Burner is enigmatically called ‘the organ with a name but no form’.

The NanJing was so named because it set out to clarify issues raised by an even older medical textbook – the HuangDi NeiJing (The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine). Ironic, then, that this statement still creates debate amongst acupuncturists, while it firmly refuses to ever be an issue amongst Western doctors. No Western doctors have ever discussed the koan that is ‘What form does the Triple Burner take?’ because (for them) the Triple Burner doesn’t exist.

Acupuncturists may not agree on what the Triple Burner is, but they do agree on what it does in the body. It behaves somewhat like a compost heap. At the bottom is the fresh manure, in the middle is the soil and at the top are the flowers and carrots. This happy harmony is how it has to be. Dung beetles and colons may not mind living in excrement, but flowers and people do. So it is with the body. The middle section is where we take the goodness from what we eat, the bottom section contains the well-rotted manure, and the upper section (heart and lungs) is where our flowers bloom.

(This may sound somewhat poetic, but poetry often contains deep truths in artistic form and this description happens to be an accurate yet extremely concise summary of the body.)

The Triple Burner is also the key to understanding Acupuncture, since it is none other than the patterns created and modelled in the body by fascia. Fascia, a substance that has no form of its own, takes the form of that which it is covering. Fascia is the defining aspect of our body; it sculpts muscles in the arm, organs in the body, even the walnutty surface of our brains. It is truly an organ with no form of its own, yet it is everywhere.

An important note about the word ‘fascia’ here, because the term seems to confuse people. It’s nothing to do the walnut interior of a freshly waxed red sports car, or even with Hitler’s insane policies. Fascia is Latin for ‘bands together’, for that is what it does – it binds together tissues. Imagine vacuum-packed vegetables, or white goods…or even meat. Meat is vacuum-packed because it keeps all the juicy goodness in. The body vacuum packs everything in the same way but it uses fascia instead of plastic. Take any organ, muscle or body part and it will be vacuum-packed in fascia.

However, the vacuum in the body lies between the fascial layers. In health, the space between the layers is squashed together like an unopened supermarket plastic bag. We know the space exists to put our groceries in, but we have to open it first.

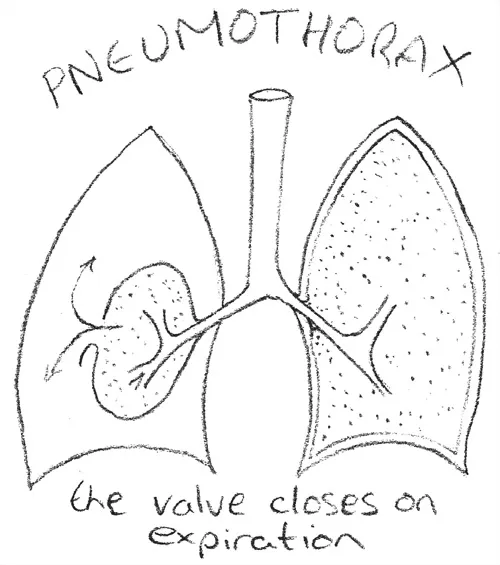

In our body the same is true; if you puncture a lung the fascial layers of lung and chest wall will naturally stay stuck together because the body maintains a negative pressure between the two. However, sometimes a ‘valve’ can form in the injured lung tissue that can stop air leaking back into the lung. As a result, the pressure between the fascial layers rises and the space opens up in the same way as your plastic bag at the supermarket checkout. Exactly the same principle is used by surgeons with keyhole surgery, but in the case of the punctured lung the condition is uncontrolled and dangerous. This condition is known as a pneumothorax and can actually kill people. The fascia itself is tiny, thin, almost transparent, but because it encases the lungs it has enormous power…the power to kill, but also, as we will find, the power of health.

Fascia is a type of connective tissue, Western medicine’s apt description of tissue that physically connects things. Connective tissue also includes bones, cartilage and even blood. Connective tissue has a matrix made and supported by the cells living within it. In bones, cartilage and fascia, this matrix is rich in collagen – a fact that is extremely important (blood is unusual in having a liquid matrix called plasma).

Fascia connects organs to muscle, to spine, to nerves… It surrounds bone and underpins skin. You find it in, around and on organs, sometimes in duplicate or even triplicate layers. Fascia is everywhere in the body and it is extremely...