![]()

PART I

OIL PRICES IN CONTEXT

![]()

1

Price Regimes, Price Series and Price Trends: Oil Shocks and Counter-Shocks in Historical Perspective

Giovanni Favero and Angela Faloppa

Metrics and Meanings

The institutional means historically adopted to fix oil prices intertwine with the metrics adopted to produce price series, and the resulting trends exerting their effects on demand and investments. Only considering these three elements in their reciprocal interrelations in the long term, it becomes possible to understand the dynamics of the oil shocks and counter-shock of the 1970s and 1980s.

The methodological approach here adopted makes reference to the sociology of knowledge and in particular to the literature on the performativity of economic theory in the creation of markets, and on the constitutive effects of historical quantification processes.1 In such a perspective, price metrics play in their turn the role of institutions, i.e. rules on which analysts and operators agree in order to quantify changes and make a complex mechanism understandable. Prices, as measured following these procedures, are then interpreted as a boundary object, performing different functions and being at the same time the result of temporary agreements between sellers and buyers, the material of further statistical analysis and elaboration into series, and a signal to decision makers and/or market operators.

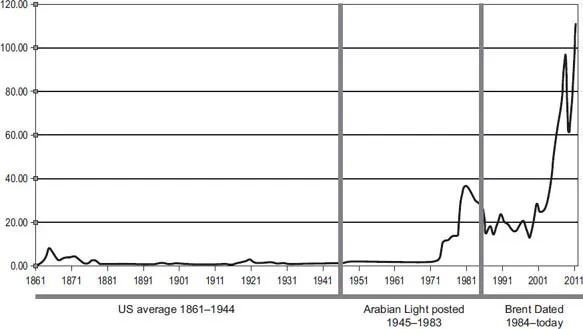

Figure 1.1 Crude oil price references, 1861 – 2011 ($/bbl). Source: BP, Statistical Review of World Energy (London, 2016).

The meaning of long historical series of prices is one favourite subject of arguments and controversies between historians and social scientists. As the late Alain Desrosières put it, the conventions of equivalence that make data comparable become sometimes dubious, as not only metrics but also their objects change over time.2

As well known, the secular series of nominal crude oil prices are the result of a patchwork putting together very different data. In the BP series (Figure 1.1), an average of US posted prices (the price at which companies were buying or selling oil, in the absence of an official exchange) is used from 1869 to 1944, then the posted price of the benchmark crude Arabian Light Crude at Ras Tanura is used up to 1983, and since 1984 the international market price (the price per unit of a traded quality of oil in the international exchange market) of the benchmark crude Brent Dated is used. The historical data published by ENI or OPEC are very similar, even if sometimes a different benchmark crude as West Texas Intermediate or others is used.

Such a statistical inconsistency is usually justified with regard to the economic and political relevance of the resulting assembled trend, whose meaningfulness is the outcome of the juxtaposition of non-comparable data. However, statistical problems concerning the source of price data do not exhaust the inconsistencies of long historical series of crude oil prices. It is the same meaning of the price of crude oil that changes over time.

In this perspective, it is possible to identify different price regimes, which do not correspond to the statistical periods identified above. From the interwar period until the 1950s, price formulas made reference to different geographical base points to add fictional transportation costs and protect the higher price of US crude from foreign competition. The reference to US domestic prices was maintained, yet the growing importance of crude oil production in the Middle East shifted the focus of price fixing on the calculation of royalties and taxes that the oil majors owed to the governments of the Middle East countries: posted prices in the Persian Gulf thus became the basis to calculate the tax paid cost. After the 1973 shock, OPEC maintained the same system, but excluded the majors from the negotiations. Such a situation lasted until the mid 1980s, when the OPEC pricing system was finally dismissed, in favour of prices directly defined on international exchange markets.

The details of this shift and the construction of a market price for oil will be discussed more in depth below. The literature on the performativity of economic theory suggests that models and algorithms have the ability to create markets.3 Making reference to this debate from a conventionalist perspective, we aim here at demonstrating that market logic is only one of the many possible raisons d'être of oil prices.4 Suffice it for the moment to highlight that the fixing of the posted price of oil followed a very different logic in 1950 and in 1980. In the same way, the role of financial instruments in determining benchmark prices has changed radically from the 1970s to today. As a consequence, also the continuity of the statistical reference can hide important transformations in its meaning, and statistical discontinuities may or may not reflect an actual change in price fixing practices.

Aiming at disentangling the metrics, the meaning and the political and economic impact of oil pricing in the long term, this chapter uses the specialised literature to reinterpret the evolution of the systems for fixing posted and correlate prices from the 1960s to the 1980s, then focuses on the emergence of a spot market for crude oil and of an interconnected futures market, concluding with some general considerations on how the interplay between the metrics in use made the oil counter-shock the foundational moment of a new oil regime.

Posted Prices as Non-Market Prices

The pricing system for internationally traded oil before the 1970s has been defined as ‘an economic logic that never corresponded to reality but which at first was close enough to be invested with a measure of plausibility’.5 Since the late 1920s a series of oligopolistic agreements fixed prices using a fictional basing point: the Gulf Plus in the 1930s, and other Equalisation Points after World War II. Such a system allowed the majors, i.e. the largest multinational oil companies, to accumulate profits to finance their vertical and horizontal expansion.

After World War II the international trade of oil radically changed, as Venezuelan and Middle Eastern crudes finally replaced US oil exports to Europe and Asia. The protection of the US domestic oil production was then ensured by a system of mandatory import quotas becoming effective in 1959,6 while the majors went on extracting oil all over the world according to the terms of the concessions. Such agreements were generating increasing revenues also for the governments of the host countries. Until 1950, their share was defined in terms of a fixed royalty per metric ton. This way, they had no relation at all with the prices at which the crude oil was sold, usually to downstream subsidiaries of the same company or following long-term contracts with buyers.

A first change happened in the early 1950s, with a gradual shift to posted prices as a basis for the calculation of ad valorem royalties and of income taxes. Posted prices at the time were unilaterally made public in a conventional way by the seller (the Western major) to give notice that it was prepared to accept a certain sum for a barrel of crude oil.7 In October 1950, Mobil was the first oil company to post its price for the Iraqi Kirkuk crude, which was followed in November by a posting for Arabian Light Crude. The introduction of posted prices was mainly related to the spread in the Middle East of the so-called 50/50 agreement, including an ad hoc tax rate on the concessionaires' net income. The posted price was then used as a tax reference price to calculate the payments the majors owed to the hosting countries. Even if posted prices were not initially used in all the 50/50 deals (introduced first in Venezuela in 1948 and in 1950 in Saudi Arabia), by 1955 all concessions contained a 50/50 clause based on the posted prices. They emerged as the best solution to provide a transparent basis for the assessment of the majors' profits. Proper market transactions were in fact extremely rare at the time, and the majors preferred to maintain the secret about the terms of long period contracts with downstream buyers.8 The only viable alternative reference were the internal transfer prices between subsidiaries of the same parent company, yet they were in their turn performing a different fiscal function, as the Western authorities required to report them to avoid tax evasion. So we may argue that the posted price emerged purposefully to assess the redistribution issues between the majors and the hosting countries without interference.

Historians of statistics know that whenever a quantitative indicator is used to automatically assess a bargained issue, or to depoliticise it, sooner or later the same indicator becomes the object of bargaining and political confrontation.9 In the same way, ‘prices used as numbers in fiscal formulas tend to become something other than prices’.10 Indeed, as posted prices became the only basis for the assessment of the tax revenue of hosting countries, they were less and less influenced by the trends and levels of supply and demand.

In 1960 OPEC was created in reaction to the cuts to posted prices decided by the majors in 1959 and 1960. Taxes and royalties were a national interest to be protected, and the first task of the newly established international organisation was to avoid any further unilateral cut to posted prices. In 1964, OPEC was able to change the calculation of the majors' taxable profits. Starting from that year, royalties were no longer detracted (‘credited’) from profits before calculating the amount of taxes due to the hosting country, but ‘expensed’ apart. This way, the final government take resulted increased by half of the royalty rate in a 50/50 tax agreement.11

Such changes went together with an accelerated increase of the world demand for oil from 1965 to 1970, and with a parallel expansion of production, in particular by OPEC countries. Such expansion created concerns about the exhaustible nature of oil reserves in producing countries, exerting an influence on their production and pricing policies. The growing tensions on pricing issues for different crude oils took to the Tehran and Tripoli regional agreements in February and April of 1971. Following OPEC's threats to cut off production, income taxes were increased to 55 per cent, posted prices were also increased and their further annual increase was provided to compensate inflation. Such agreements had a scarce financial impact, yet signalled the establishment of a new power relationship between the majors and OPEC. They also included a plan for the administration of prices to last until 1975, irrespective of variations in supply and demand.12 But the following events proved that a five-year span was too long for planning in turbulent times.

In August 1971, the oil producing countries perceived the cancellation of the US dollar's direct convertibility into gold and the increasing dollar inflation as a direct threat to their nominal incomes. In October 1972 OPEC countries asked then for a participation share in the upstream operations of their concessionaires, and so were endowed with a proportional quantity of crude oil they could sell back to the oil companies or to third party buyers.13 The 1972 participation agreement opened a first crack in the vertically integrated structure of the industry, paving the way to the future emergence of a proper market for crude oil. Yet its immediate consequence was the appearance of three different prices for a barrel of oil: the posted price, the government or official s...