Daniel Willingham, a professor focusing on the application of cognitive psychology to education, lays out the facts for us: “While it is true that some people are better at math than others – just like some are better than others at writing or building cabinets or anything else – it is also true that the vast majority of people are fully capable of learning [school] mathematics.”1 It is simply not true, in the majority of cases, that students can’t do maths.

However, it is clear that in order to be successful, some students require greater levels of perseverance and hard work. For these individuals, and in fact all students, we need to ensure that we are challenging them by having high expectations of both the level of thinking we expect them to achieve and their attitude to working hard, while also (where necessary) supporting them by scaffolding the challenge.

Before we can consider what this challenge looks like in our classroom, we must first consider what learning might look like. Therein lies a problem. We might, for example, observe that students are busy completing lots of work, and we could infer from this that they are learning. But perhaps these students are busy because the work is too easy for them. Professor Robert Coe suggests that these and other easily observable features are “poor proxies for learning”. The problem we have is that learning is invisible.

Poor proxies for learning

(easily observed, but not really about learning)

Figure 1.1. Poor proxies for learning2

This leaves us with a rather awkward issue. If these things are not indicative of learning taking place, then what is? A good place to start is to reflect upon what we mean by ‘learning’.

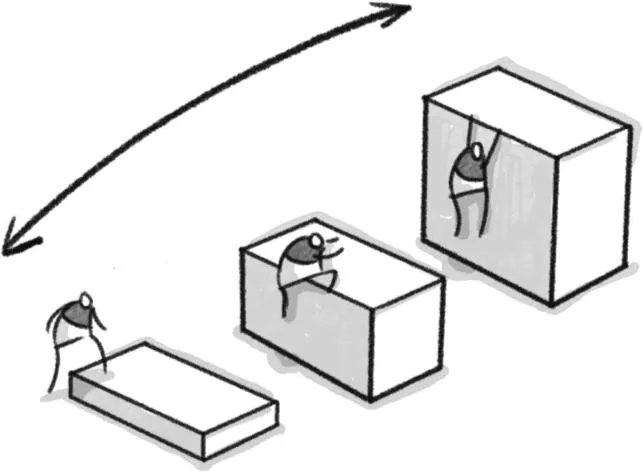

Educational psychologists Paul Kirschner and John Sweller define learning as “a change in long-term memory”.3 Long-term memory is where we store everything – our very own Wikipedia, if you like. Daniel Willingham suggests that “memory is the residue of thought”.4 By putting these together, we arrive at this: learning is a permanent change in long-term memory caused by thinking which happens over time (Figure 1.2).5

It is now clear that challenging students to think is crucial. Frustratingly, this is not as straightforward as it sounds. Not only do we need to carefully manage both what our students are thinking about and how hard they are thinking, but we need to ensure that they are thinking in the first place. Willingham says that “People are naturally curious, but we are not naturally good thinkers; unless the cognitive conditions are right, we will avoid thinking.”6 Hence the importance of focusing student attention.

Students learn what they attend to,7 meaning that what they learn is greatly influenced by what their attention is focused on. Craig Barton’s Swiss roll incident is a great example of the importance of attention. Craig had set his Year 7s an unfamiliar problem to identify the minimum number of cuts needed to share seven Swiss rolls equally between twelve people. Wanting to model the solution, he dutifully purchased said Swiss rolls, rolled up his sleeves and gave his students a memorable ‘maths in action’ experience. Many years later, a student lamented that maths was boring and not fun like “the Swiss roll lesson”. Yet when the student was asked what she thought the lesson was about she replied, “Swiss rolls”.8

In this scenario, the student’s attention was focused on Swiss rolls instead of on the underlying mathematical ideas that were being explored. The student only remembered what she attended to – Swiss rolls. This episode reveals why strategies such as enquiry and discovery learning with minimal guidance can be ineffective. They fail because student attention is not sufficiently attuned to what it is they need to learn. Thus our model for learning becomes that in Figure 1.3.

Next we need to ask ourselves what happens once attention is suitably focused. This is where working memory, the gatekeeper to long-term memory, comes into play. To enter into long-term memory, information must pass through the working memory, which has a very limited capacity. Overwhelming working memory is referred to as cognitive overload, and occurs when students are made to attend to too many things. They consequently fail to learn anything. The converse is when students fail to learn anything new because the cognitive load is too low. We will examine how to manage cognitive load in Chapter 2.

When Cambridge Mathematics pooled the research on working memory, they found that it is particularly important when learning maths. They also found that around a quarter of the differences in ma...