![]()

CHAPTER 1

Getting Organised for Useful Analytical Results

1 IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNICATION AND PLANNING

In the scenario described below, poor communication between an analyst and a researcher leads the analyst to do work on the samples that does not give what the researcher wanted and expected. Both the researcher and the analyst need essential information from each other to ensure that the work done on the samples is suitable, useful and well received by the researcher; and satisfying for the analyst.

While reading the scenario you are asked to consider the situation that the analyst has to address. At the end of it there are some explanatory notes but, before turning to them, you are asked to think about how the unsatisfactory outcome might have been avoided.

Suppose that the following conversation (which unfortunately is not entirely fanciful) took place between a researcher and an analyst in the laboratory:

Researcher: I am going to harvest some plants from an experiment next week. I need to know the amount of P in them. Can you do that analysis for me?

Analyst: Yes, P determination in plant material is one of our standard procedures – when do you want to bring them in?

Researcher: Well, if I harvest them on Thursday, can I bring them first thing Friday morning?

Analyst: I’ll check my work diary . . . yes that will be all right. That’s agreed then, I’ll see you on Friday morning, with the samples.

However, there was a slight change of plan. The researcher had to leave early, but he entrusted the samples to a colleague to take them to the laboratory. So on Friday morning the samples duly arrived in five carrier bags with a note to the analyst saying:

‘Here are the plant samples for analysis of P. I hope the results will be ready when I return in 2 weeks time’.

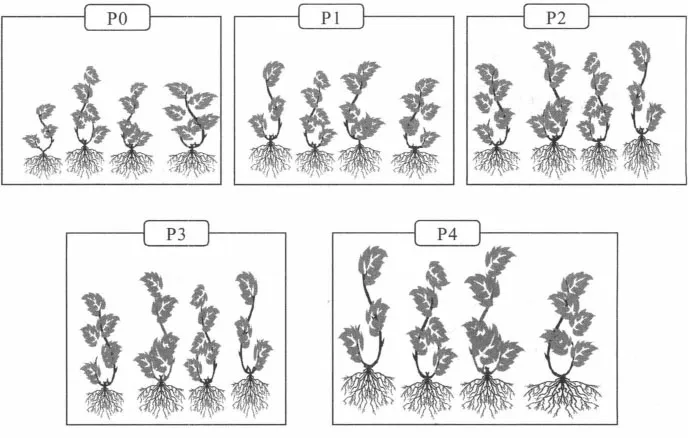

The carrier bags were labelled PO, PI, P2, P3 and P4, and each bag contained four young cotton plants, complete with roots and with soil adhering (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Plants received for analysis

Perhaps this analyst has not received samples from this researcher before and the researcher has not had an analysis done previously at this laboratory. So the analyst has to use her initiative in deciding how to deal with these samples.

The samples cannot be kept until the researcher returns:

•Do you foresee any difficulties for the analyst in making decisions on how to proceed?

•What would you advise her to do?

•What material should she take for analysis:

–All the material provided?

–Plants with soil removed?

–Plants with soil and roots removed?

–Leaves only?

•How many samples are there:

–Five samples, one per treatment – each made by bulking together material from four plants?

–20 samples – i.e. four replicates of one plant from each treatment?

•Do you think these decisions are important in relation to the purpose of the analysis or for any other reasons?

The work was at risk because the analyst and researcher each assumed too much of the other – at this stage they had not communicated adequately. Probably the researcher did not know enough about the process of analysis to question properly the service being offered. Probably the analyst is used to doing a particular procedure and assumed that it would match what was expected or needed in this case.

The analyst could not confirm any points with the researcher, but, being a sensible and helpful person, she proceeded on what seemed to her to be reasonable assumptions:

•Cut off the roots and soil from the plants.

•Take five aluminium trays, label them P0 to P4 and put the four plant tops from each bag into the appropriate tray.

•Put the trays in the oven to dry the samples at 80 °C overnight.

•Crush the dried plants in each tray and grind up all the material in a tray together to pass through a 1 mm sieve to make a homogeneous sample from each tray.

•Continue with the determination of the concentration of P (g kg −1) in the five samples.

When the researcher returned, the laboratory was pleased to be able to report the results they had obtained (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Analytical results

| Treatment | P0 | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 |

| P g kg−1 | 0.96 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.26 | 6.35 |

Now did the researcher have some comments and questions:

•It looks as though the foliar spray treatment of P4 was very effective.

•Are the results statistically significant?

•There was about 1 kg of soil in each pot, so does the g kg−1 mean the same as g P taken up by the plant per pot?

•I want to work out what proportion of the P added was in the plants in each treatment.

What would you expect the analyst’s responses to be?

•We didn’t wash the plants so some of the P determined in the sprayed ones may be only dried P on the surface, but not absorbed in the plants.

(Which probably means: you didn’t tell me the plants were sprayed.)

•We can’t do a test of statistical significance because there is no replication.

(Which probably means: you should have labelled the plants as separate samples showing that there were four replicates of each treatment.)

•The g kg −1 means g P per 1000 g of dry plant material.

(Which probably means: I thought anyone would know that.)

•We don’t know how much dry material there was per pot so we can’t calculate how much P was used per pot.

(Which probably means: why didn’t you weigh the plants or ask us to; or at least measure them in some way.)

•Here is our invoice for £50 + VAT.

(Which probably means: well it’s your loss, not mine.)

So both were very dissatisfied with the results of their efforts and no doubt each felt that it was all the fault of the other.

1.1 Activity

Take a few minutes to think about this situation. Is there any other information that the analyst should have and any other information that the researcher might think it is necessary to provide? List on a separate piece of paper as many points as you can that the analyst or the researcher need to know about the work requested:

•What the researcher needs to know.

•What the analyst needs to know.

1.2 Can We Avoid Misunderstandings?

Quite often a researcher has not thought through all that he or she is asking the laboratory to do and so is unprepared to provide all this relevant information. They may even feel that the analyst is being obstructive in demanding it. But you can see how things may go badly wrong if points are not clarified at an early stage.

Together the analyst and the researcher can work out a strategy to try to ensure that the analytical results obtained are as useful as possible to the purpose intended. It may be necessary for the researcher to organise transport from the field to the laboratory or to arrange for plot yields to be weighed in the field. Perhaps the samples will need to be kept in a refrigerator, pending their further preparation, so the analyst may need to organise that space is available in the refrigerator when required.

It would be wise of the researcher to write down the points of strategy agreed with the analyst and to leave a copy in the laboratory as confirmation of the arrangements. Such records form part of a workfile in a laboratory accredited to ISO/IEC 17025 (see Chapter 4, Section 6.1).

Questions:

•Why does the analyst want to know what types of plants are to be harvested?

•What problems may arise if the amount of sample material provided is (a) too large or (b) too small?

1.3 Notes on this Section

The researcher needs to know, for example:

•The set charge (if any) per sample for the test.

•Whether there may be a further charge depending on the amount of work required for sample preparation.

•An estimate of the time the analysis will take.

•The form in which the results will be presented.

•Whether, assuming the analysis goes well, the information produced will be useful and likely to add value to the experiment.

•If the amount of material in each sample is adequate or too little or too much.

The analyst needs to know:

•How many samples there will be.

•The deadline (if any) for reporting the results.

•What plants are being harvested.

•What material will be received (i.e. tops, leaves or whole plants).

•What will be the size of the sample (i.e. how may it be subsampled: fresh or dried).

•Whether the samples need washing (i. e. whether the plots will have received any sprays or dressings containing P).

•Whether any further work is required on the samples (i.e. are there implications regarding how the samples should be treated or stored?).

•Whether the researcher wants to know the P concentration in the plant material, or some measure of total plant content of P per plot (i.e. will the data collected allow the required calculations to be made?).

•If the weight of whole plants (fresh or dry) is needed what steps are to be taken to remove soil (or growing medium) and will the plants be really fresh when received in the laboratory?

•Overall, will the ...