eBook - ePub

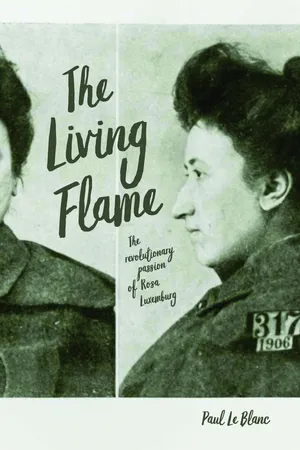

Living Flame

The Revolutionary Passion of Rosa Luxemburg

Paul Le Blanc

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Living Flame

The Revolutionary Passion of Rosa Luxemburg

Paul Le Blanc

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Rosa Luxemburg, brilliant early 20th century German revolutionary, comes alive in a rich set of essays on her life, ideas, and lasting influence. The essays deal not only with her remarkable contributions to political, social and economic theory, but also touch on her vibrant personality and intimate friendships. This collection, the fruit of more than four decades of involvement with Luxemburg's work, simultaneously showcases her penetratingly intellectual, political and deeply humanistic qualities.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Living Flame als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Living Flame von Paul Le Blanc im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Politics & International Relations & Communism, Post-Communism & Socialism. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Verlag

Haymarket BooksISBN

9781642590906

1

ROSA LUXEMBURG

(1871–1919)

(1871–1919)

Rosa Luxemburg was born in a Poland divided under German and Russian domination, and she played a role in the revolutionary movement of each country. Her influence has been global, however, since her contributions place her within the very heart of the Marxist tradition.

Part of a cultured and well-to-do family in Warsaw, Luxemburg was an exceptionally bright child who was encouraged to pursue an education in Poland and then at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, where she received a doctorate in economics with a dissertation titled “The Economic Development of Poland.” She became active in the revolutionary socialist movement while still in her teens, soon rising into the leadership circle of the Social-Democratic Party of the Kingdom of Poland, a militant group whose antinationalist orientation caused it to be outpaced by other currents emphasizing the cause of Polish independence.

Luxemburg’s working-class internationalism, however, prompted her move to Germany in order to play a more substantial role in the massive and influential Social Democratic Party (SPD) there. Luxemburg soon occupied a place in the revolutionary wing of the socialist movement, gaining considerable respect and also attracting considerable hostility.

QUALITY OF MARXISM

Among Luxemburg’s best known early writings are her polemic Reform or Revolution? (1899) and her more reflective “Stagnation and Progress of Marxism” (1903), both of which give a sense of the quality of her Marxism.1 The first involves a debate with a prominent SPD theoretician, Eduard Bernstein. The revolutionary approach of Karl Marx, according to Bernstein, was no longer relevant to modern capitalism and new German realities; he was convinced that the trade unions and reform efforts within the German parliament, both associated with the practice of the SPD, promised the piecemeal elimination of various oppressive aspects of capitalism and a gradual evolution to socialism. This approach was consistent with the actual practice of the SPD, he argued, not the commitment to the old notion that the working class should take political power in order to inaugurate the socialist transformation. In his view, this was related to a natural tendency in capitalist development for the economy to become socially organized and therefore to evolve in a socialist direction.

Luxemburg sharply challenged this view. She scoffed at Bernstein’s method of “weighing minutely the good and bad sides of social reform and social revolution … in the same manner in which cinnamon or pepper is weighed out.” This method of analysis, in which one could select methods of historical development “out of pleasure from the historical counter of history, just as one chooses hot or cold sausages,” constituted the abandonment of “dialectics and … the materialist conception of history” that had guided Marx for an inferior method leading in the opposite direction—pushing “the labor movement into bourgeois paths” and “paralyze completely the proletarian class struggle.” Following this method, the SPD program would become “not the realization of socialism, but the reform of capitalism.” The very nature of capitalism—at the heart of the functioning of the capitalist economy—involved maximizing profits for the capitalist minority through a relentless exploitation of the working-class majority. It is true, she noted, that under capitalism “production takes on a progressively increasing social character,” but the capitalist form of this “social character”—including the rise and incredible expansion of powerful economic corporations—would mean that “capitalist antagonisms, capitalist exploitation, the oppression of labor-power, are augmented to the extreme.”2

Luxemburg insisted that Marx’s insight—that “capitalism, as a result of its own inner contradictions, moves toward a point when it will be unbalanced, when it will simply become impossible”—remained as valid as ever. This would cause capitalism’s defenders to resist and push back both social reforms and the increasingly “inconvenient” democratic forms that had been conceded in the face of previous revolutionary struggles. She was quite critical of the undemocratic limitations of Germany’s parliamentary system—hobbled by the power of monarchy, aristocracy, and big business—and she dismissed Bernstein’s notion that this “poultry-yard of bourgeois parliamentarism” could be utilized “to realize the most formidable social transformation of history, the passage from capitalism to socialism.” It would become necessary for the workers to push past these limitations, in the direction of genuine “rule by the people” (that is, to political rule by the working class). “In a word, democracy is indispensable not because it renders superfluous the conquest of political power by the proletariat, but because it renders this conquest both necessary and possible.”3

Arguing that the socialist movement must fight for “the union of the broad popular masses with an aim reaching beyond the existing social order, the union of the daily struggle with the great world transformation” from capitalism to socialism, Luxemburg saw revolutionary Marxism as the most effective means for helping the labor movement to avoid two negative extremes: “abandoning the mass character of the [SPD] or abandoning its final aim [and] falling into bourgeois reformism …”4

On the other hand, Luxemburg warned that, to a large extent, what passed for “Marxism” in the mass socialist movement was far more limited and dogmatic than the far more complex and nuanced body of thought of Marx (“his detailed and comprehensive analysis of capitalist economy, and … his method of historical research with its immeasurable field of application”). She argued that much of this had gone beyond the initial practical needs of the working-class movement, and that “it is not true, as far as the practical struggle is concerned, Marx is out of date, that we have superseded Marx. On the contrary, it is because we have not yet learned to make adequate use of the most important mental weapons in the Marxist arsenal … [because the labor movement had not felt] the urgent need of them in the earlier stages of our struggle.”5

Luxemburg’s belief was that developments of the twentieth century would create such an “urgent need,” and that rather than allowing the limited “orthodox Marxism” to co-exist with the reformist practice hailed by Bernstein, the SPD and the world socialist movement would need to be revitalized with the more profoundly revolutionary orientation represented by Marx’s actual perspectives. At the same time, the spread of the critical Marxist approach (what she termed “the Marxist method of research [being] socialized”) would help theorists and activists in the workers’ movement to come to grips with the new developments confronting them, with innovative analyses, strategies, and tactics.

ANALYSES OF CAPITALISM AND IMPERIALISM

Applying the dialectical approach to her economic studies, Luxemburg understood capitalism as an expansive system driven by the dynamic of accumulation. Capital in the form of money is invested in capital in the form of raw materials and tools and labor-power, which is transformed—by the squeezing of actual labor out of the labor-power of the workers—into capital in the form of the commodities thereby produced, whose increased value is realized through the sale of the commodities for more money than was originally invested, which is the increased capital out of which the capitalist extracts his profits, only to be driven to invest more capital for the purpose of achieving ever greater capital accumulation.

Luxemburg’s analysis of the capital accumulation process involves a complex critique of the second volume of Marx’s Capital. As part of her resolution of what she considers to be an underdeveloped and incomplete aspect of Marx’s analysis of how surplus value is realized, she focuses on the global dynamics of the capitalist system and argues that imperialism is at the heart of capitalist development.

In her classic The Accumulation of Capital (1913) she offers an incisive economic analysis of imperialism. There are several distinctive features of Luxemburg’s theory of imperialism that sets it off from that of other leading Marxists. She makes a great deal of the co-existence in the world of different cultures, different types of society, and different modes of production (i.e., different economic systems). Historically the dominant form of economy worldwide was the communal hunting and gathering mode of production, which was succeeded in many areas by a more or less communistic agricultural form of economy (which she characterized as a primitive “peasant economy”). This was succeeded in some areas by nonegalitarian societies dominated by militarily powerful elites, constituting modes of production that she labeled “slave economy” and “feudalism.” Sometimes coexisting with, sometimes superseding, these modes of production was a “simple commodity production” in which artisans and farmers, for example, would produce commodities for the market in order to trade or sell for the purpose of acquiring other commodities that they might need or want. This simple commodity mode of production is different from the capitalist mode of production, which is driven by the already-described capital accumulation process, overseen by an increasingly wealthy and powerful capitalist minority.

Three features especially differentiate the analysis in The Accumulation of Capital from the perspectives of other prominent Marxists.

1.Luxemburg advances a controversial conceptualization of imperialism’s relationship to the exploitation of the working class in advanced capitalist countries. Because workers receive less value than they create, they are unable to purchase and consume all that is produced. This underconsumption means that capitalists must expand into noncapitalist areas, seeking markets as well as raw materials and investment opportunities (particularly new sources of labor) outside of the capitalist economic sphere.

2.Another distinctive quality of her conceptualization of imperialism is that it is not restricted to “the highest stage” or “latest stage” of capitalism. Rather, imperialism is something that one finds at the earliest beginnings of capitalism—in the period of what Marx calls “primitive capitalist accumulation”6—and which continues nonstop, with increasing and overwhelming reach and velocity, down to the present. Or as she puts it, “capitalism in its full maturity also depends in all respects on non-capitalist strata and social organizations existing side by side with it [and] since the accumulation of capital becomes impossible in all points without non-capitalist surroundings, we cannot gain a true picture of it by assuming the exclusive and absolute domination of the capitalist mode of production.”7

3.Another special feature of Luxemburg’s contribution is her anthropological sensitivity to the impact of capitalist expansion on the rich variety of the world’s peoples and cultures. The survey of capitalist expansionism’s impact in her Accumulation of Capital includes such examples as the destruction of the English peasants and artisans; the destruction of the Native American peoples (the so-called Indians); the enslavement of African peoples by the European powers; the ruination of small farmers in the midwestern and western regions of the United States; the onslaught of French colonialism in Algeria; the onslaught of British colonialism in India; British incursions into China, with special reference to the Opium Wars; and the onslaught of British colonialism in South Africa (with lengthy reference to the three-way struggle of Black African peoples, the Dutch Boers, and the British).

No less dramatic is Luxemburg’s perception of the economic role of militarism in the globalization of the market economy. “Militarism fulfils a quite definite function in the history of capital, accompanying as it does every historical phase of accumulation,” she commented, noting that it was decisive in subordinating portions of the world to exploitation by capitalist enterprise. It played an increasingly explosive role in rivalry between competing imperialist powers. More than this, military spending “is in itself a province of accumulation,” making the modern state a primary “buyer for the mass of products containing the capitalized surplus value,” although in fact, in the form of taxes, “the workers foot the bill.”8

REVOLUTIONARY STRATEGY AND ORGANIZATION

Luxemburg was profoundly critical of conservative developments in the SPD. An increasingly powerful tendency inside the party and trade union leadership was quietly moving along the reformist path outlined by Bernstein. This path, she prophetically insisted, would not lead gradually to socialism at all, but to the gradual accommodation and subjugation of the socialist movement to the authoritarian proclivities, the brutal realities, and the violent dynamics of the capitalist system.

Luxemburg’s revolutionary orientation resonated throughout much of the German labor movement. There were, however, powerful trade union leaders who despised her. They were insulted by her comment, in The Mass Strike: The Political Party and the Trade Unions (1906), that trade union struggles can only be like the labor of Sisyphus (rolling the boulder up a hill, only to have capitalist dynamics push the gains back down again) and that only socialism will secure permanent gains for the working class. Although she argued that it is necessary for trade unions to wage that struggle in order to defend and improve the workers’ conditions in the here-and-now, this did not soften her barbed observation that “the specialization of professional activity as trade-union leaders, as well as the naturally restricted horizon which is bound up with disconnected economic struggles in a peaceful period, leads only too easily, among trade union officials, to bureaucratism and a certain narrowness of outlook.”9

As Luxemburg explained it, the workings and contradictions of capitalism can sometimes result in what she called a “violent and sudden jerk which disturbs the momentary equilibrium of everyday social life,” aggravating “deep-seated, long-suppressed resentment” among workers and other social layers, resulting in an explosive and spontaneous reaction on a mass scale—in the form of strikes spreading through an industry and sometimes involving many, most, or all occupations and workplaces in one or more regions. Such mass strikes can go far beyond economic issues, sometimes involving whole communities in mass demonstrations and street battles, and are the means by which workers seek to “grasp at new political rights and attempt to defend existing ones.”10 Once such strikes begin, there can occur tremendous solidarity, discipline, and effective organization. But they have an elemental quality, which defies any notion of revolutionary blueprints being drawn up in advance.

Luxemburg believed that what she defined as “the most enlightened, most class-conscious vanguard of the proletariat” (among whom she included the SPD in Germany, along with organized socialist parties of other countries) should play an active role not only when such explosions occur, but also beforehand in helping to educate and organize more and more workers in preparation for such developments, which would enable socialist parties to assume leadership of the whole movement. She did not think such upsurges would necessarily result in socialist revolution, but she believed that they would become “the starting point of a feverish work of organization” that would embrace more of the working class, enabling it to fight for reforms in a manner that would help prepare it for the revolutionary struggle: “From the whirlwin...