eBook - ePub

Ethics: The Basics, 2nd Edition

John Mizzoni

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Ethics: The Basics, 2nd Edition

John Mizzoni

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Updated and revised, Ethics: The Basics, Second Edition, introduces students to fundamental ethical concepts, principles, theories, and traditions while providing them with the conceptual tools necessary to think critically about ethical issues.

- Introduces students to core philosophical problems in ethics in a uniquely reader-friendly manner

- Lays out clearly and simply a rich collection of ethical concepts, principles, theories, and traditions that are prevalent in today's society

- Considers western and non-western viewpoints and religious interpretations of ethical principles

- Offers a framework for students to think about and navigate through an array of philosophical questions about ethics

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Ethics: The Basics, 2nd Edition als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Ethics: The Basics, 2nd Edition von John Mizzoni im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Philosophy & Ethics & Moral Philosophy. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Chapter 1

Relative Ethics or Universal Ethics?

Iqbal is a boy, seven years of age, who must work 12 hours a day weaving rugs. In his culture child labor is customary. Around the world, in fact, there are millions of children who work to earn money instead of going to school. A recent report numbered child laborers, between five and 14 years of age, at over 200 million.

In some cultures, in order to protect young women from sexual advances of boys and men, they undergo at puberty the process of “breast ironing,” a cultural practice in which their breasts are pounded and massaged in order to make them disappear.

It is not a strong concern in some cultures that adults have heterosexual sex with young teens and children; and in other cultures, it is customary for men to have sexual relations with younger boys.

One last example of this kind. In order to preserve their chastity and honor, in some cultures girls from seven to thirteen years of age have their clitoris surgically removed – it is known as female circumcision. Opponents of the practice call it female genital mutilation.

Are these practices ethical? What makes a cultural practice or social norm ethical or unethical?

Everyone is familiar with philosophizing about where ethical rules and standards come from. At one time or another we have all asked the questions, What makes something right or wrong? and Where does right and wrong come from?

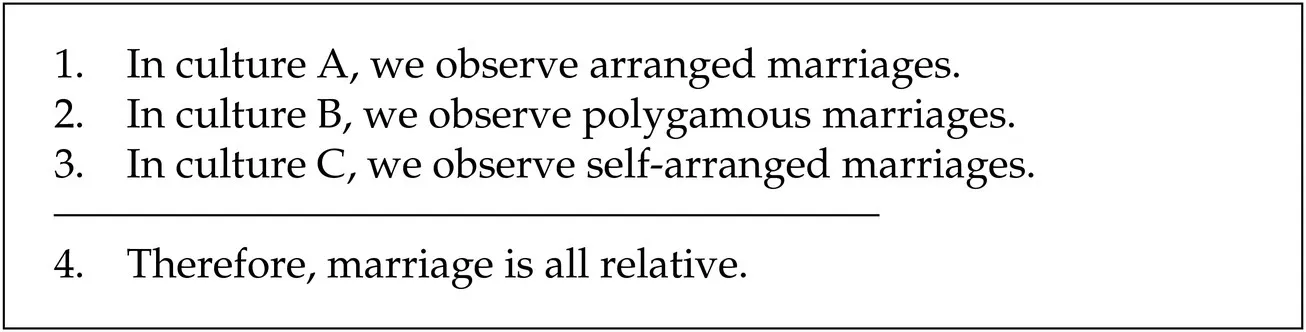

1.1 Relative Ethics

These may seem to be very broad ethical questions, yet the existence of child labor, breast ironing, female circumcision, and divergent sexual practices make them very real questions – and in some cases, where children’s lives are at stake, quite urgent. People have thought about and struggled with these kinds of questions about the origins of ethics for many centuries. When one faces these hard questions, thinks about the philosophical problem of the origins of ethics, and becomes aware of the great variety of human customs the world over, it becomes tempting to say that right and wrong are just a matter of opinion, since what is regarded as right or wrong in one culture may not be seen in the same way in another culture. Right and wrong seem culturally relative. Also, some practices that were once regarded as right, either a century ago or 20 years ago, are nowadays regarded as wrong. Ethical standards seem to change, and there is so much disagreement between cultural practices that ethical relativism, the view that right and wrong are always relative, seems justified (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

Those who defend the idea that ethics is relative emphasize the differences among our ethical judgments and the differences among various ethical traditions. Some relativists call these cultural and ethical traditions folkways. This is a helpful concept for understanding ethical relativism because it highlights that the ways and customs are simply developed by average people (folk) over long periods of time. Here is how the twentieth‐century social scientist William G. Sumner describes the folkways:

The folkways…are not creations of human purpose and wit. They are like products of natural forces which men unconsciously set in operation, or they are like the instinctive ways of animals, which are developed out of experience, which reach a final form of maximum adaptation to an interest, which are handed down by tradition and admit of no exception or variation, yet change to meet new conditions, still within the same limited methods, and without rational reflection or purpose. From this it results that all the life of human beings, in all ages and stages of culture, is primarily controlled by a vast mass of folkways handed down from the earliest existence of the race. (Sumner 1906: 19–20)

Folkways: The concept that customs are developed by average people (folk) over long periods of time.

Something is right, an ethical relativist will say, if it is consistent with a given society’s folkways and wrong if it goes against a society’s folkways. Relative ethics will say that in cultures where female circumcision has taken place for centuries, it is right to continue to circumcise young girls, and wrong to attempt to change this tradition.

Relativists believe that ethical differences between cultures are irreconcilable. On their view, irreconcilable differences are actually quite predictable because each society today has its own unique history and it is out of this history that a society’s ethical values and standards have been forged. Around the globe, each society has its own unique history; consequently, each society has its own unique set of ethical standards. Relativists would say that if there are any agreements between cultures on ethical values, standards, or issues, we should not place any importance on that accidental fact, because, after all, the true nature of ethics is relative, and the origin of ethics lies in each society’s unique history.

1.2 Universal Ethics

Not everyone, though, is content with the relativist’s rather skeptical answer to the question about the ultimate nature and origin of ethics. Instead of a relativist answer to the question, plenty of people have asserted that not everything is relative. A critic of relativism will say that not everything in ethics is relative, because some aspects of ethics are universal. Those who hold this view are called ethical universalists. In contrast to the ethical relativist who claims that all ethics is relative, the universalists contend that there are at least some ethical values, standards, or principles that are not relative. And this somewhat modest claim is all that a universalist needs to challenge the relativist’s generalization that all ethics is relative. An easy way to grasp what universalists are talking about is to consider the concept of universal human rights. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was created in 1948 by the United Nations General Assembly. It has inspired close to 100 bills of rights for new nations. People who believe in universal human rights hold ethical universalism: they believe there are certain rights that all human beings have, no matter what culture or society they belong to. An ethical relativist will deny this, and maintain that rights are meaningful only within a particular cultural tradition, not in a universal sense.

1.3 Cultural Relativism or Ethical Relativism?

In order to achieve a bit more clarity on the issue of relativism, we must consider the difference between cultural relativism and ethical relativism. Cultural relativism is the observation that, as a matter of fact, different cultures have different practices, standards, and values. Child labor, breast ironing, divergent sexual practices, and female circumcision are examples of practices that are customary in some cultures and would be seen as ethical in those cultures. In other cultures, however, such practices are not customary, and are seen as unethical. If we took the time to study different cultures, as anthropologists and other social scientists do, we would see that there is no shortage of examples such as these. As the anthropologist Ruth Benedict has put it: “The diversity of cultures can be endlessly documented” (1934: 45).

As examples, consider wife and child battering, polygamy, cannibalism, or infanticide. There are some cultures (subcultures at least) that endorse these practices as morally acceptable. Western culture, by contrast, regards these practices as immoral and illegal. It seems to be true, therefore, just as a matter of fact, that different cultures have different ethical standards on at least some matters. By comparing different cultures, we can easily see differences between them, not just on ethical matters, but on many different levels.

Cultural Relativism: The theory that, as a matter of fact, different cultures have different practices, standards, and values.

What we need to notice about ethical relativism, in contrast with cultural relativism, is that ethical relativism makes a much stronger and more controversial claim about the nature of ethics. Ethical relativism is the view that all ethical standards are relative, to the degree that there are no permanent, universal, objective values or standards. This view, though, cannot be justified by simply comparing different cultures and noticing the differences between them. The ethical relativist’s claim goes beyond observation and predicts that all ethical standards, even the ones we have not ye...