eBook - ePub

A Concise History of World Population

Massimo Livi-Bacci

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

A Concise History of World Population

Massimo Livi-Bacci

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

The latest edition of this classic text has been updated to reflect current trends and implications for future demographic developments. The areas of Africa, international migration and population and environment have been strengthened and statistical information has been updated throughout.

- A new edition of this classic history of demography text, which has been updated to strengthen the major subject areas of Africa, international migration and population and the environment

- Includes the latest statistical information, including the 2015 UN population projections revision and developments in China's population policy

- Information is presented in a clear and simple form, with academic material presented accessibly for the undergraduate audience whilst still maintaining the interest of higher level students and scholars

- The text covers issues that are crucial to the future of every species by encouraging humanity's search for ways to prevent future demographic catastrophes brought about by environmental or human agency

- Analyses the changing patterns of world population growth, including the effects of migration, war, disease, technology and culture

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist A Concise History of World Population als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu A Concise History of World Population von Massimo Livi-Bacci im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Scienze sociali & Demografia. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1

The Space and Strategy of Demographic Growth

1.1 Humans and Animals

Throughout human history population has been synonymous with prosperity, stability, and security. A valley or plain teeming with houses, farms, and villages has always been a sign of well‐being. Traveling from Verona to Vicenza, Goethe remarked with pleasure: “One sees a continuous range of foothills … dotted with villages, castles and isolated houses … we drove on a wide, straight and well‐kept road through fertile fields … The road is much used and by every sort of person.”1 The effects of a long history of good government were evident, much as in the ordered Sienese fourteenth‐century landscapes of the Lorenzetti brothers. Similarly, Cortés was unable to restrain his enthusiasm when he gazed over the valley of Mexico and saw the lagoons bordered by villages and trafficked by canoes, the great city, and the market (in a square more than double the size of the entire city of Salamanca) that “accommodated every day more than sixty thousand individuals who bought and sold every imaginable sort of merchandise.”2

This should come as no surprise. A densely populated region is implicit proof of a stable social order, of nonprecarious human relations, and of well‐utilized natural resources. Only a large population can mobilize the human resources necessary to build houses, cities, roads, bridges, ports, and canals. If anything, it is abandonment and desertion rather than abundant population that has historically dismayed the traveler.

Population, then, might be seen as a crude index of prosperity. The million inhabitants of the Paleolithic Age, the 10 million of the Neolithic Age, the 100 million of the Bronze Age, the billion of the Industrial Revolution, or the 10 billion that we may attain by mid twenty‐first century certainly represent more than simple demographic growth. Even these few figures tell us that demographic growth has not been uniform over time. Periods of expansion have alternated with others of stagnation and even decline; and the interpretation of these, even for relatively recent historical periods, is not an easy task. We must answer questions that are as straightforward in appearance as they are complex in substance: Why are we 7 billion today and not more or less, say 100 billion or 100 million? Why has demographic growth, from prehistoric times to the present, followed a particular path rather than any of numerous other possibilities? These questions are difficult but worth considering, since the numerical progress of population has been, if not dictated, at least constrained by many forces and obstacles that have determined the general direction of that path. To begin with, we can categorize these forces and obstacles as biological and environmental. The former are linked to the laws of mortality and reproduction that determine the rate of demographic growth; the latter determines the resistance that these laws encounter and further regulates the rate of growth. Moreover, biological and environmental factors affect one another reciprocally and so are not independent of one another.

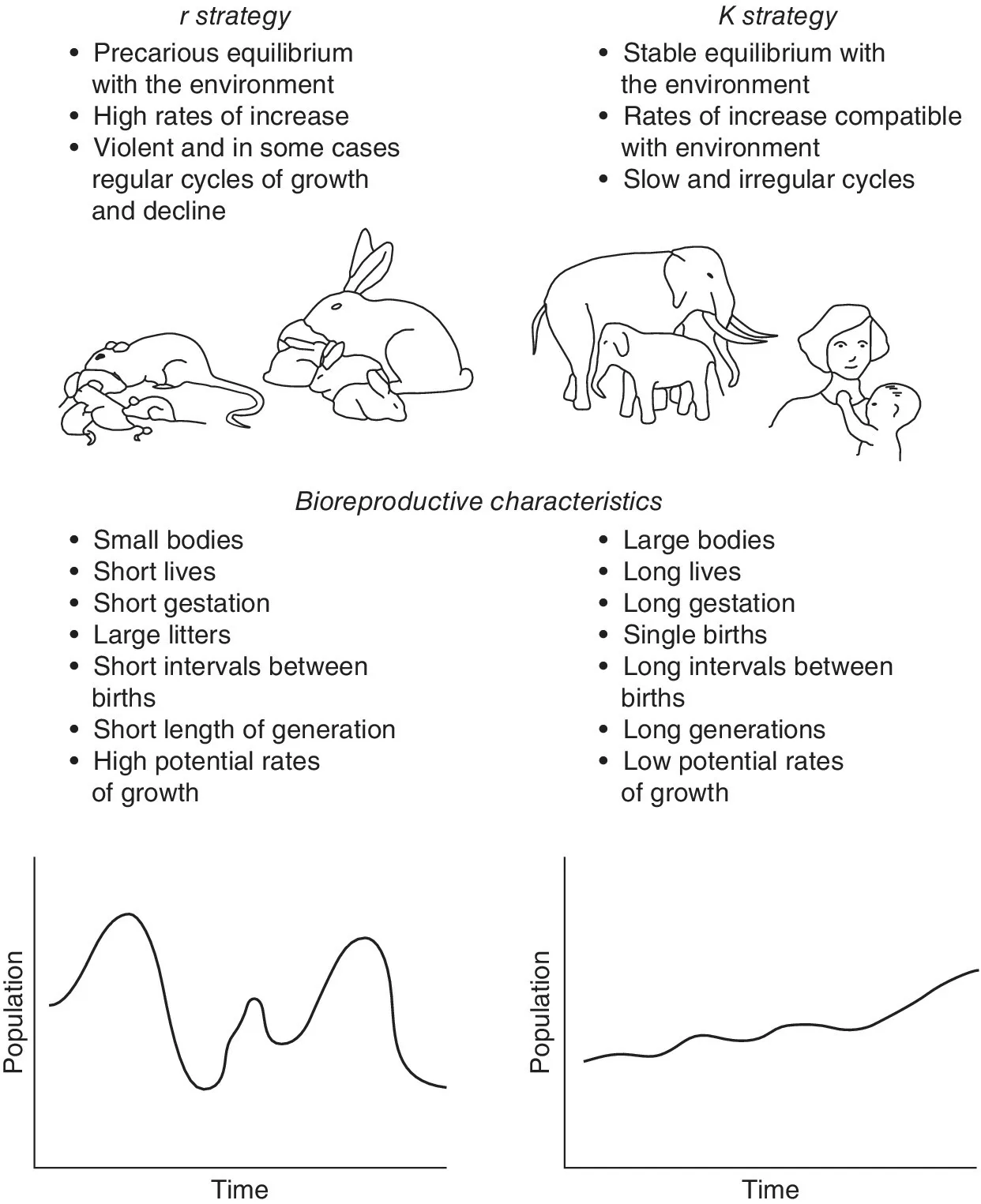

Every living collectivity develops particular strategies of survival and reproduction, which translate into potential and effective growth rates of varying velocity. A brief analysis of these strategies will serve as the best introduction to consideration of the specific case of the human species. Biologists have identified two large categories of vital strategies, called r and K, which actually represent simplifications of a continuum.3 Insects, fish, and some small mammals practice an r‐strategy: these organisms live in generally unstable environments and take advantage of favorable periods (annually or seasonally) to reproduce prolifically, even though the probability of offspring survival is small. It is just because of this environmental instability, however, that they must depend upon large numbers, because “life is a lottery and it makes sense simply to buy many tickets.”4 r‐strategy organisms go through many violent cycles with phases of rapid increase and decrease.

A much different strategy is that practiced by K‐type organisms – mammals, particularly medium and large ones, and some birds – who colonize relatively stable environments, albeit populated with competitors, predators, and parasites. K‐strategy organisms are forced by selective and environmental pressure to compete for survival, which in turn requires considerable investment of time and energy for the raising of offspring. This investment is only possible if the number of offspring is small.

r and K strategies characterize two well‐differentiated groups of organisms (Figure 1.1). The first are suited to small animals having a short life span, minimal intervals between generations, brief gestation periods, short intervals between births, and large litters. K strategies, on the other hand, are associated with larger animals, long life spans, long intervals between generations and between births, and single births.

Figure 1.1 r strategy and K strategy.

Figure 1.2 records the relation between body size (length) and the interval between successive generations for a wide array of living organisms: as the first increases, so does the second. It can also be demonstrated that the rate of growth of various species (limiting ourselves to mammals) varies more...