![]()

1 Introducing Critical Media Studies

How We Know What We Know

Everything we know is learned in one of two ways.1 The first way is somatically. These are the things we know through direct sensory perception of our environment. We know what some things look, smell, feel, sound, or taste like because we personally have seen, smelled, felt, heard, or tasted them. One of the authors of this text knows, for example, that “Rocky Mountain oysters” (bull testicles) are especially chewy because he tried them once at a country and western bar. In short, some of what we know is based on first-hand, unmediated experience. But the things we know through direct sensory perception make up a very small percentage of the total things we know. The vast majority of what we know comes to us a second way, symbolically. These are the things we know through someone or something such as a parent, friend, teacher, museum, textbook, photograph, radio, film, television, or the internet. This type of information is mediated, meaning that it came to us via some indirect channel or medium. The word medium is derived from the Latin word medius, which means “middle” or that which comes between two things: the way that television and the Discovery Channel might come between us and the animals of the Serengeti, for instance.

In the past 30 seconds, those readers who have never eaten Rocky Mountain oysters now know they are chewy, as that information has been communicated to them through, or mediated by, this book. When we stop to think about all the things we know, we suddenly realize that the vast majority of what we know is mediated. We may know something about China even if we have never been there thanks to Wikipedia; we may know something about King George VI even though he died long before we were born thanks to The King’s Speech (2010); we may even know something about the particulars of conducting a homicide investigation even though we have likely never conducted one thanks to the crime drama CSI. The mass media account, it would seem, for much of what we know (and do not know) today. But this has not always been the case.

Before the invention of mass media, the spoken or written word was the primary medium for conveying information and ideas. This method of communication had several significant and interrelated limitations. First, as the transmission of information was tied to the available means of transportation (foot, horse, buggy, boat, locomotive, or automobile depending upon the time period), its dissemination was extraordinarily slow, especially over great distances like continents and oceans. Second, because information could not easily be reproduced and distributed, its scope was extremely limited. Third, since information often passed through multiple channels (people), each of which altered it, if only slightly, there was a high probability of message distortion. Simply put, there was no way to communicate a uniform message to a large group of people in distant places quickly prior to the advent of the modern mass media. What distinguishes mass media like print, radio, and television from individual media like human speech and hand-written letters, then, is precisely their unique capacity to address large audiences in remote locations with relative efficiency.

Critical Media Studies is about the social and cultural consequences of that revolutionary capability. Recognizing that mass media are, first and foremost, communication technologies that increasingly mediate both what we know and how we know, this book surveys a variety of perspectives for evaluating and assessing the role of mass media in our daily lives. Whether listening to an iPod while walking across campus, sharing pictures with friends on Facebook, receiving the latest sports scores via your smartphone, sharing your favorite YouTube video over email, or settling in for the most recent episode of The Big Bang Theory or Downton Abbey, the mass media are regular fixtures of everyday life. But before beginning to explore the specific and complex roles that mass media play in our lives, it is worth looking, first, at who they are, when they originated, and how they have developed.

Categorizing Mass Media

As is perhaps already evident, media is a very broad term that includes a diverse array of communication technologies such as cave drawings, speech, smoke signals, letters, books, telegraphy, telephony, magazines, newspapers, radio, film, television, smartphones, video games, and networked computers to name just a few. But this book is principally concerned with mass media or those communication technologies that have the potential to reach a large audience in remote locations. What distinguishes mass media from individual media, then, is not merely audience size. While a graduation speaker or musician may address as many as 40,000 people at once in a stadium, for instance, neither one is mass mediated because the audience is not remote. Now, of course, if a Lady Gaga concert is being broadcast live via satellite, those watching at home on their televisions or streaming it live over the internet are experiencing it through mass media. Mass media collapse the distance between artist and audience, then. Working from this definition, we have organized the mass media into four sub-categories: print media, motion picture and sound recording, broadcast media, and new media. These categories, like all acts of classification, are arbitrary, meaning that they emphasize certain features of the media they group together at the expense of others. Nonetheless, we offer these categories as one way of conceptually organizing mass communication technologies.

Print media

In an electronically saturated world like the one in which we live today, it is easy to overlook the historical legacy and contemporary transformations of print media, the first mass medium. German printer Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable-type printing press in 1450, sparking a revolution in the ways that human beings could disseminate, preserve, and ultimately relate to knowledge. Printed materials before the advent of the press were costly and rare, but the invention of movable type allowed for the (relatively) cheap production of a diverse array of pamphlets, books, and other items. This flourishing of printed materials touched almost every aspect of human life. Suddenly knowledge could be recorded for future generations in libraries or religious texts, and social power increasingly hinged upon literacy and ownership of printed materials. Most importantly, the press allowed for an unprecedented circulation of knowledge to far-flung cities across Europe. Although still limited by class distinctions, access to information from outside of one’s immediate context was a real possibility. Mass media was born.

Not long after the settlement of Jamestown in the USA in 1607, the colonies established their first printing press. Located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the press was printing popular religious tracts such as the Bay Psalm Book, a 148-page collection of English translations of Hebrew, by 1640.2 Although much of the early printing in the colonies was religion-oriented, novels such as Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Tom Jones (1749), imported from England, were also popular. Religious tracts were eventually followed by almanacs, newspapers, and magazines. The most well-known early almanac, Poor Richard’s Almanac, which included information on the weather along with some political opinions, was printed from 1733 to 1757 by Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia. Although various cities had short-lived or local non-daily newspapers in the 1700s, the New York Sun, which is considered the first successful mass-circulation newspaper, did not begin operations until 1833.3 The failure of earlier newspapers is often attributed to the fact that they were small operations run by local printers. It was not until newspapers began using editors and receiving substantial financial backing – first from political parties and later from wealthy elites like Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst – that the newspaper industry mushroomed.

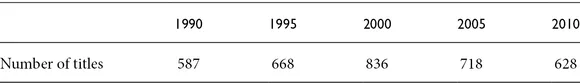

Table 1.1 Number of consumer magazine titles in the USA

Source: Audit Bureau of Circulations.

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the newspaper industry experienced rapid growth. This trend continued until 1973, at which point there were 1,774 daily newspapers with a combined circulation of 63.1 million copies.4 This meant that about 92 percent of US households were subscribing to a daily newspaper in 1973. Since then, however, newspaper production and circulation has steadily declined. In 2011, the total number of daily newspapers printed in the USA was 1,382 and they had a combined circulation of 44.4 million copies or less than 40 percent of US households.

In many ways, the history of the magazine industry in the USA closely mirrors that of the newspaper industry. It began somewhat unsteadily, underwent tremendous growth, and is currently experiencing a period of considerable instability. The first US magazine, American Magazine, was published in 1741. But the magazine boom did not really begin until the mid-nineteenth century. And though the industry continued to experience growth throughout the twentieth century, more recently it has suffered a decline in both the total number of titles (Table 1.1) and paid circulation (Table 1.2). Table 1.1 illustrates that the number of consumer magazine titles in the USA grew by 30 percent from 1990 to 2000 before declining by nearly 25 percent from 2000 to 2010.

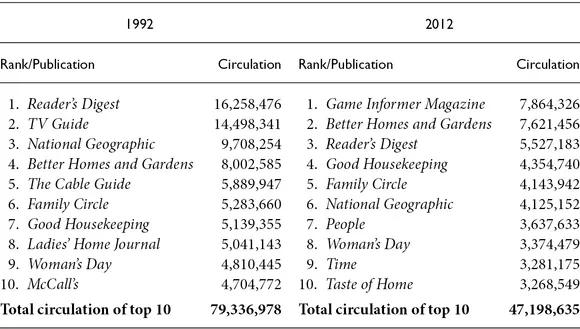

Moreover, as Table 1.2 shows, the total paid circulation of the top 10 magazines in 2012 is more than 30 million less than the total paid circulation of the top 10 magazines 20 years earlier. Interestingly, the highest circulating magazine in 2012, Game Informer Magazine, had existed for only 1 year in 1992, while the second highest circulating magazine in 1992, TV Guide, no longer exists. The book publishing industry has, until very recently, not experienced the deep losses occurring in the newspaper and magazine industries over the past two decades. But in 2012, unit sales of traditional paper books fell by about 9 percent for the third year in a row; adult non-fiction was the hardest hit, falling 13 percent.5 Despite declining circulation and unit sales in the newspaper, magazine, and book industries, Americans are still reading. But how they are reading – thanks to e-books and online newspapers and magazines – is changing both rapidly and dramatically.

Table 1.2 Top 10 US consumer magazines by paid circulation in 1992 and 2012*

Source: Adweek, March 29, 1993; Alliance for Audited Media, February 7, 2013. *Data exclude magazines whose circulation is tied to membership benefits (i.e. AARP The Magazine [formerly Modern Maturity] and AARP Bulletin).

Motion picture and sound recording

Sound recording and motion pictures may seem like an odd pairing at first, but their histories are deeply intertwined thanks in large part to Thomas Edison. In the span of 15 years, Edison and his assistant, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, created what would later develop into the first two new mass media since print. Edison’s first invention, of the phonograph in 1877, was a device that played recorded sound, and his second, the kinetoscope in 1892, was an early motion picture device that showed short, silent films in peep-show fashi...