eBook - ePub

The Art Direction Handbook for Film & Television

Michael Rizzo

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 544 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The Art Direction Handbook for Film & Television

Michael Rizzo

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

In this new and expanded edition of The Art Direction Handbook, author Michael Rizzo now covers art direction for television, in addition to updated coverage of film design. This comprehensive, professional manual details the set-up of the art department and the day-to-day job duties: scouting for locations, research, executing the design concept, supervising scenery construction, and surviving production. Beyond that, there is an emphasis on not just how to do the job, but how to succeed and secure other jobs. Rounding out the text is an extensive collection of useful forms and checklists, as well as interviews with prominent art directors.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The Art Direction Handbook for Film & Television un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The Art Direction Handbook for Film & Television de Michael Rizzo en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Medien & darstellende Kunst y Film & Video. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Pre-Production Process

Chapter 1

Introduction

Art directing is somewhat like snowboarding or skydiving—the essence of the activity is in the doing. In that way, an art director is by nature an action figure. The definitive art director is also a unique amalgam of contradictions. On one hand, creativity reigns with few boundaries; on the other hand, practicality takes primary focus. Balancing pairs of opposites, like art and commerce, make the job of art directing unique and challenging. Getting right down to it, an art director is best described as a design manager.

How can this be? Doesn’t the job description of art direction include phrases like “seminal creative force” or “visionary?” It certainly does, but indirectly so. As a design manager, the Art Director on a film project operates as a department manager in form but as an artist in substance. In other words, business decisions for the art department are made on a daily basis, enabling the physical side of creative film production to happen according to schedule, while creativity provides the foundation for those decisions. Before we venture too far, perhaps it’s best to establish a fundamental difference between the “Production Designer” and the “Art Director.”

Clarification

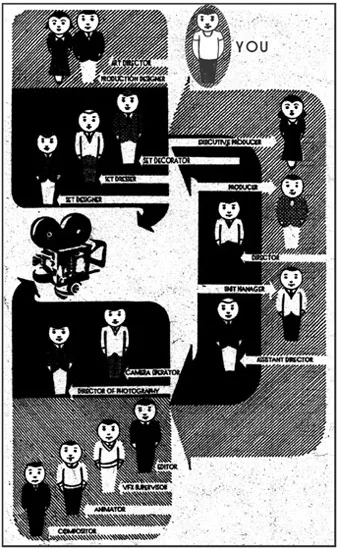

Talent and title are important aspects of filmmaking, generally referred to as billing. When we examine the art department hierarchy, the Production Designer is found at the top with the Art Director close at hand (see Figure 1.1). As a side-by-side relationship, the production designer and art director complement one another. Although the terms “production designer” and “art director” are constantly used in substitution for one another, they are not interchangeable or synonymous. Why? Sharing the same hierarchy level of the film pyramid with the Director and Cinematographer, the Production Designer delivers the visual concept of a film through the design and construction of physical scenery. In this sense, the designer is the seminal, creative force of the art department. Referring back to the image of the action figure, an art director drives the process of design from sketch to actual physical scenery. The Art Director, or design manager, heads and runs the art department, interfaces with all other departments, supports the art department arm of the shooting crew, oversees scenery fabrication, and controls all aspects of the department expense and scenery budgets. Although an art director’s creative input is essential to support the initial creative ideas of the designer, the totality of the design in terms of conception and responsibility belongs solely to the designer. This idea of symbiotic, creative support is echoed in a recent interview with art director Linda Berger (Angelmaker, Forrest Gump, Death Becomes Her):

Figure 1.1 Film Hierarchy, Simplified.

Interview with Linda Berger

- ■ Why are you an art director?

I have been thinking about the silent film designers most of my adult life. In the past ten years [1994—2004], especially through my work with the Art Directors Guild Film Society, I have begun to look at them within the whole context of art direction. As a professional in the field of moviemaking who started out in the theater, my earliest adventure in the networking process was to go to New York City right out of design school at the Goodman and the Art Institute of Chicago— with no connections, no anything except my education, a handful of very close friends, and two seasons of professional summer stock in Pennsylvania and upstate New York. When I arrived in New York City, I did everything I could to find my way and continue to learn. I was an Off-Broadway lighting electrician, a lighting designer’s assistant at the Brooklyn Academy of Music for the ballet and modern dance, and worked in costume shops at Lincoln Center and in the individual shops of costume designers. I worked props and painted scenery. I also worked in television as an animation assistant and did lots of commercials. Eventually, I became an Off-Broadway theatrical designer. The first time I saw my name on the marquee from across the street, I almost fainted. Regardless, I challenged myself to meet people and explore the possibilities. It thrilled me to walk around the city and actually stand in the places where great designers stood. Now, many years later, I continue to do exactly that when I work with a production designer. And, to have eventually met some of them, I allow myself to climb within their skins so I can see from their angle of vision in order to fully understand how to contribute to their vision. That’s how I view art direction.I can’t speak for everyone, but I think most people look at art direction from the outside in. There’s nothing wrong with that. I tend to do it from the inside out; it’s my instinct to do it that way. Expressing myself as an art director in this way allows me to leapfrog through time and enter the mind and spirit of any great artist or designer. Oftentimes, certain art directors have such a difficult time doing their jobs because they are in competition with the designer. Most importantly, they’re missing a great opportunity. In its own way, projecting myself into the designer’s mind that way is very gratifying because I learn so much about myself in the process. It’s thrilling to make another person’s vision a reality. - ■ Art directors share a great creative component with the designer, but do you also see yourself as a creative manager, for the most part?

I’m not fully doing my job if I’m just nuts-and-bolts managing the art department. The daily process is a creative process in how I deal with people, how I process instructions from above, how I convey ideas to those who need answers from me, and how I think on my feet when I’m on set. Understanding my designer’s tastes and aesthetic responses supports how I supply what is needed at any given moment. How I fulfill my job changes slightly as I work with different designers, given the differences in perspective. In the same way, the designer has to think the way the director thinks in order to do his or her job properly.

There’s a line of thought and function that connects everything in a collaborative environment like a movie. Storytelling drives what we do. Two questions are always asked. What is the story we want to tell, and how are we going to tell it? The biggest part of my job, then, is storytelling through the interpretation of the production designer and director’s vision.1

Together, both the designer and the creative manager strategize about the functioning of the art department and scenery output, but the Art Director alone spearheads design management on a tactical level by delegating responsibility and guiding each task to completion. With the creative integrity of art directing kept in mind, this book will deconstruct this creative department head more as a marketing and operations manager rather than a seminal creative force. In the end, the reader will view the Art Director not only as a peerless, organizing force for the art department but also as a powerful shaper of policy and systems management for the larger film or television project.

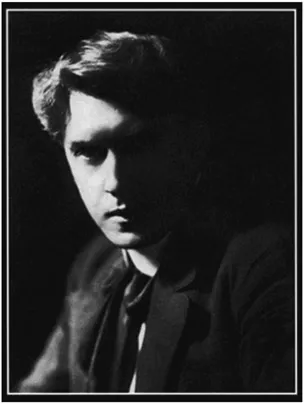

The First Art Director: Wilfred Buckland

All production designers are art directors, and formerly, there were no production designers at all—there were only art directors. In earliest American film memory, the first creative moviemaker to be given the title of “Art Director” was Wilfred Buckland (Figure 1.2) who is widely credited as one of the most important influences “on the look of Hollywood cinema.”2

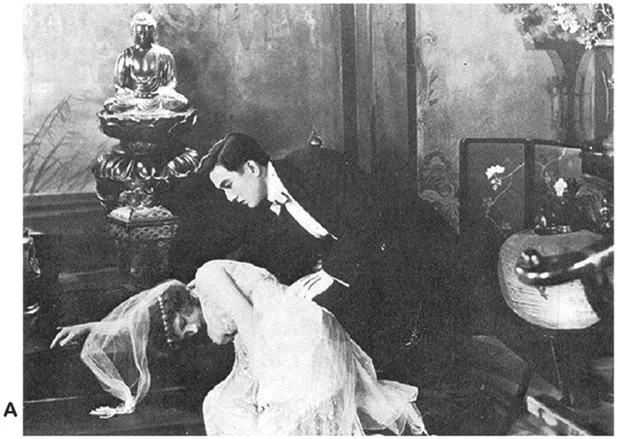

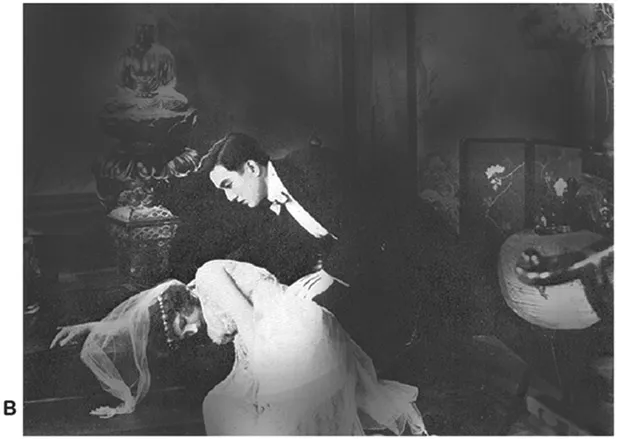

Previously, he had designed Broadway theatrical productions, and later for the fledgling movie business developed a form of minimalist, Caravaggio-like lighting that engulfed the characters in darkness except for a single source of side illumination. This dramatic theatrical effect quickly became a silent film trademark known as “Lasky lighting,” after the production company that made The Cheat (1915), his most successful film (see Figure 1.3). It was also one of Cecil B. DeMille’s masterpieces, shot in Standard 35mm spherical 1.37:1 format, combining all the ingredients typical of the infamous DeMille style “a mixture of sex, sadism, and sacrifice, washed down with lurid melodrama.”3 Buckland’s lighting contributions were groundbreaking. Two signature scenes in the film—the branding of the heroine by her wealthy Japanese paramour and the subsequent shooting scene—are lit with such theatrical richness and integrity that our attention is just as adroitly manipulated today as it was during its initial release.

Figure 1.2 Wilfred Buckland, the first Hollywood Art Director.

This early maverick’s scenic designs created an equally powerful tour de force for filmgoing audiences in the early 1920s. Towering 40 feet above Santa Monica Boulevard and La Brea Avenue, King Richard’s castle, the centerpiece for Douglas Fairbank’s Robin Hood (1922), is arguably the largest set ever constructed in Hollywood history. It took 500 workmen three solid months to build. Considering Los Angeles was more of a wide spot in the road then, the silhouette of the com pleted castle set could be seen for miles. It exemplified Buckland’s penchant for creating extravagant, naturalistic sets, and it attests to his flair and flexibility as an early art director. Allan Dwan, director and trained engineer, recalled:

We worked out a couple of interesting engineering stunts for the big sets. On the interiors, the walls meshed together with a matrix, which we designed and built, so they could be put together rapidly in sections. The interior of the castle was very vast—too big to light with ordinary arcs. We didn’t have enough. It was an open set, and certain sections were blacked out to give the right atmosphere. So to light them we constructed huge tin reflectors, about twenty feet across, which picked up the sun and shot the light back onto the arches inside. Then we could make effects. 4

This set was larger than life in all ways—from the completion of the steel-frame, reinforced, working drawbridge, signifying the end of set construction, to the fact that the shooting of the film on its massive sets was a big tourist attraction (see Figure 1.4). And the magic of the Dream Factory continues to stir our imaginations.

Figure 1.3

A) Production still from The Cheat,

A) Production still from The Cheat,

B) An example of a “Lasky Lighting” effect for the same scene, designed by Wilfred Buckland.

Figure 1.4

A) Perspective aerial close-up of Robin Hood castle,

A) Perspective aerial close-up of Robin Hood castle,

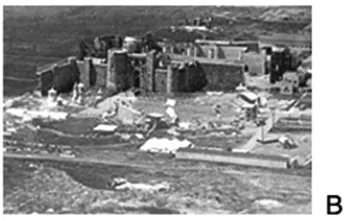

B) High aerial shot of Robin Hood castle,

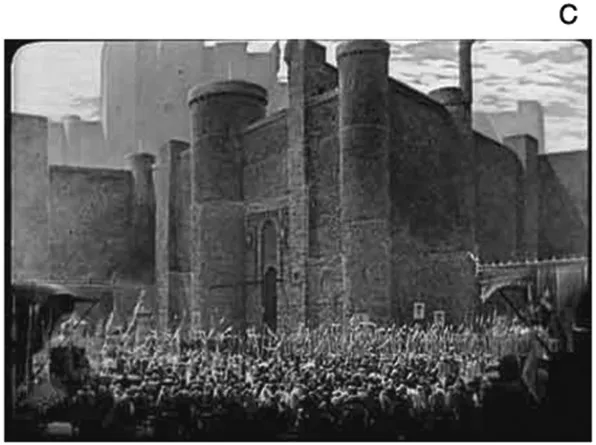

C) Production shot of the Robin Hood castle: The glass painted matte above the existing set suggests additional architecture within or beyond,

D) Interior: Great Hall with the Robin Hood castle,

E) Interior: A battle scene is fought just inside the main courtyard entrance of the castle set,

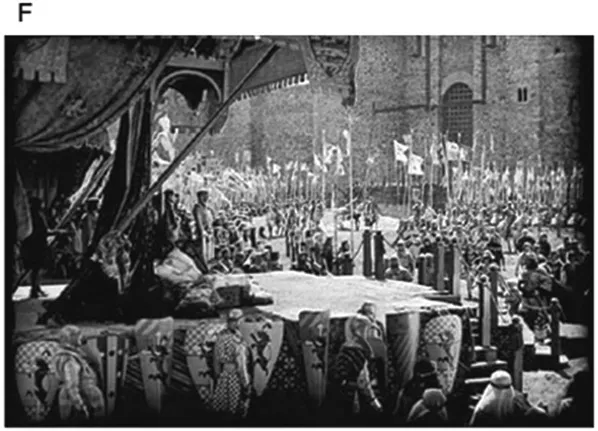

F) Holding court just outside the Robin Hood castle walls.

Under the steady but tumultuous employ of Cecil B. De Mille, Buckland was a prolific film designer—more than 80 f...