eBook - ePub

EU Shipping Law

Vincent Power

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 1,842 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

EU Shipping Law

Vincent Power

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

A previous winner of the Comité Maritime International's Albert Lilar Prize for the best shipping law book worldwide, EU Shipping Law is the foremost reference work for professionals in this area. This third edition has been completely revised to include developments in the competition/antitrust regime, new safety and environmental rules, and rules governing security and ports. It includes detailed commentary and analysis of almost every aspect of EU law as it affects shipping.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es EU Shipping Law un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a EU Shipping Law de Vincent Power en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Law y Maritime Law. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

A. SCOPE OF THIS BOOK

1.001 This book is an introduction to several aspects of the law of the European Union (“EU”)1 as it relates to shipping or maritime transport.2 Instead of being a general textbook on EU law, this book takes a specialist approach to EU law by identifying and examining many of the aspects of EU law most relevant to shipping.3 Given the breadth of the topic, the book concentrates on issues most relevant to shipping because almost any area of EU law is potentially relevant to the sector.

1.002 EU shipping law is an important topic because, as was stated in the Athens Declaration of 7 May 2014 (more formally entitled Mid-Term Review of the EU’s Maritime Transport Policy until 2018 and Outlook to 2020),

“the EU is highly dependent on maritime transport4 both for its internal and external trade since 75% of the Union’s imports and exports and 37% of the internal trade transit through seaports5 and that shipping is a highly mobile industry facing increasingly fierce competition from third countries”.6

The EU is now a major source of shipping law.

B. THE EUROPEAN UNION

Introduction

1.003 Before introducing EU shipping law, it is useful to provide some background on the EU generally. The EU is the most sophisticated international organisation in the world. It comprises 28 Member States7 who have ceded some elements of their sovereignty to create the EU. The conduct of these Member States along with other participants in the sector such as shipping companies, ports and seafarers can now be controlled in certain circumstances by the EU; in return, however, they have rights and opportunities which they would not otherwise possess (e.g. the right to establish businesses or work in other Member States on an equal footing with nationals in those Member States).8

Evolution of the European Union

1.004 The EU is the successor of the European Economic Community9 (“EEC”) which was founded in 1957. The EEC became the European Community (“EC”) in the 1990s and is now the EU.

1.005 The EU is the product of the phenomenon known as European Integration. After the ravages of the Second World War in Europe, a plan was devised known as the Schuman Plan10 advocating that France and Germany should form closer links between the two countries (who had fought each other three times over the previous 70 years) to place the principal weapons of war at the time (namely, coal and steel) under the supervision of a common authority11 and in a common market12 so as to minimise the risk of war between them and in Europe generally. This plan led to the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community (“ECSC”) in 1952. While the original plan was just to involve France and Germany, four other States (i.e. Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) also participated in the ECSC. The ECSC was successful and it was quickly realised that the successes in the context of coal and steel could be extended to other economic sectors (i.e. to the economy generally including the shipping sector). This led to the establishment of the EEC and the European Atomic Energy Community (“EAEC”) in 1957.

1.006 The ECSC had come into existence in 1952 with six Member States.13 These six States then formed the EEC and EAEC in 1957.14 In 1973, the membership of the three Communities (i.e. the ECSC, EEC and EAEC) grew to nine States;15 there were ten States when Greece acceded in 1981; in 1986, two Iberian States16 joined; three States joined in 1995;17 ten States joined in 2004 in the largest accession ever;18 two further States joined in 2007;19 and one State joined in 2013.20 Today, there are therefore 28 Member States in the EU: Austria; Belgium; Bulgaria; Croatia, Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; France; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Ireland; Italy; Latvia; Lithuania; Luxembourg; Malta; Netherlands; Poland; Portugal; Romania; Slovakia; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; and United Kingdom. Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iceland, Kosovo, Montenegro, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine are among the potential future Member States.

1.007 The EU is an evolving phenomenon. Generally speaking, it is expanding, rather than contracting, in terms of membership, competence and activities. It has experienced dynamic development punctuated by occasional stagnation but rarely permanent reversal. It began life in the 1950s as a group of three intergovernmental organisations21 and is now an economic, monetary22 and political union23 of global significance. There were times in the 1970s and 1980s when it suffered degrees of paralysis. In recent years, it suffered a crisis related to the euro currency and the Economic and Monetary Union (“EMU”) but it has survived the crisis. It will face further challenges in the future including, at the time of writing, a crisis over migration and the possible exit from the EU by the United Kingdom. However, the EU is now playing a significant role in world affairs as a collective unit having diplomatic relations and standing around the world. The EU developed a special relationship with some neighbouring States by the formation of the European Economic Area (“EEA”) with effect from 1994 and today those States are Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein. Equally, the EU is forming relationships in different spheres throughout the world. The EU, as a separate entity from its Member States, has the power to conclude certain types of international agreements within its sphere of competence and has concluded many such agreements to date. Ultimately, the EU evolves and acquires new powers because its Member States confer new powers upon it.

The EU is the world’s largest economic bloc

1.008 The EU is the world’s largest economic bloc. There is no doubt that the EU has long been forced, in the words of the European Parliament many years ago, to “speak with one voice and to adopt a common position”.24 It represents around 7% of the world’s population, constitutes the top trading partner for 80 countries around the world but about 23% of the world’s nominal gross domestic product (“GDP”) and represents 16% of global exports and imports. It is the world’s largest exporter of goods25 and the second largest importer.26

1.009 The EU’s Statistical Pocketbook 2017 (the most recent available at the time of writing) puts the EU into a global context (Table 1.1).

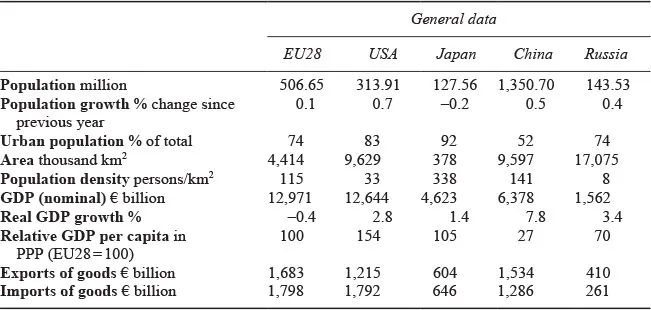

Table 1.1 Comparison EU28 – World

Source: Eurostat, World Bank. Relative GDP per capita and currency conversion rates: own calculations based on World Bank data (2012 data used).

Notes

EU28: area, population: including French overseas departments.

EU28: trade: only extra-EU trade.

EU28: area, population: including French overseas departments.

EU28: trade: only extra-EU trade.

Population

1.010 The EU has a population of just over 500 million. It is therefore the third most populous area in the world after China and India. It is more populous than the USA. The three largest Member States in terms of population are Germany (with 81 million people), France (with 66 million people) and the UK (with 64 million people).27 Its Member States represent a range in terms of population from these three large States to States such as Cyprus and Malta with relatively small populations.

The internal market

1.011 One of the core elements of the EU is the notion of the internal market which means that goods and services must be able to move freely within the EU (subject to very limited exceptions, i.e. the “internal market”) and there would be a common external tariff vis-à-vis the rest of the world (i.e. the customs union). This internal market (or common market) has been at the heart of the EU project since the 1950s. Initially, the notion was that States were less likely to go to war if they traded intensively with each other but now there is an inherent economic merit in having an internal market apart altogether from the prevention of war because of the efficiencies created by a large “home” market (i.e. the whole of the EU).

1.012 Establishing an internal market has always been difficult. Some Member States (or, sometimes some sectoral interests within those States) have sought to erect barriers to trade.28 While progress was made in the 1960s, the completion of the internal market had still not been achieved by the early 1980s. So a programme, the Internal Market Programme (known colloquially as the “1992 Programme” because the aim was to complete the internal market programme by the end of 1992) was devised by the Commission in 1985. The plan devised involved 279 measures to integrate the national markets of the Member States into one single or internal market. The internal market programme achieved a great dea...