Part 1

TRAINING AND EXERCISES

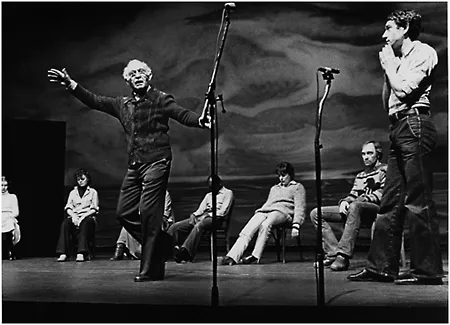

Editor’s note: This section records Lee Strasberg’s own words as he oversaw the exercises for the Actor’s Unit, the first two hours of the traditional four-hour session. The exercises include relaxation, sense memory, emotional memory, the private moment, the animal exercise, song and dance, and voice exercises. In the Actor’s Unit, Lee emphasizes relaxation and concentration as the backbone of the work. He talks to the students about eliminating tension, the role of habits that confine expression, and how to relax in the chair. To help actors take control, he describes the use of sound in eliminating emotional tension, and discusses the “abstract or additional movement,” which tests the actor’s ability to follow their own commands and break habits. As will be clear from the transcriptions, Lee’s ability to focus on and communicate with individuals, discern and analyze their acting problems, and use of the exercises illustrate the depth of his understanding of how to develop craft in acting. Also clear from the classes is one of Lee’s deepest beliefs, “that actors must make a commitment to train themselves and continue to work on their craft throughout their careers”; the importance of taking classes and continuing to work with a teacher as a guide is a point he stressed to all of his students.

Lee Strasberg on training

The human being has an extraordinary capacity and can be trained. While the other arts use different materials for expression like words, notes, paint, and train the voice, the speech, and the body, the actor himself is the instrument of expression which calls for special care like a rare Stradivarius. In our work, we develop the actor’s concentration and power of observation. We train the imagination, senses and emotions, helping the actor to expand the ability to conceive more than the ordinary. Our training nurtures creativity, which is the highest material that can be used for art.

Talent alone isn’t enough. What makes for greatness in the actor? Greatness needs that extra effort, which is commitment. When someone with a nice voice who’s been singing a while suddenly becomes great, what’s happened? The voice hasn’t changed that much. It’s that the singer commits fully and completely. Otherwise there’s a half-hold on the voice, like a batter that swings, but not in a committed way, resulting in the ball not going where he wants. When Babe Ruth swung, he pointed to where he wanted the ball to go, and it went to that spot. He had that sense of commitment and courage, of not being afraid to be wrong. The Babe had played enough to know that sometime or another he’ll connect. Actors also need a strong will to connect. That can only be done with continuity, commitment, and courage.

As in most fields of artistic endeavor, however, the fundamentals of the actor’s craft must be practiced daily or else you go backwards. The violinist has to continue practicing after becoming a major violinist. If he stops practicing, he loses his skill. This applies to the other arts as well. When a writer writes a novel and then begins to take it easy, the seeds of his creation dry up. Pablo Casals, the cellist and great instrumentalist of all time, kept practicing until his last year at 93. People asked him why he still practiced. He said, “To get better.” He was right. If he didn’t practice, his skills would not stay at the same level; he’d get worse. Actors must make a commitment to train daily and to work on their craft throughout their careers.

Most actors forget to do the training work and remember only the scene work. Some become stars before they achieve technical maturity. They assume that the training work has already been done and will always be there by itself, but when actors stop working on their craft, they imitate what already has been done, and, after three months, they become stale. After Stanislavski had a heart attack and couldn’t work or act anymore, he continued to do fifteen or twenty minutes of exercises a day, and, after fifty-odd years or more in the theater, I still do exercises for fifteen minutes every day.

To heighten yourself as an actor, you also need to know as much as possible about the theater and its history. Learn what came before you. As an essential part of your training, study the great actors of the past, and investigate material that exists – plays, novels, and short stories. Read Stanislavski, Edward Gordon Craig, Henry Irving, Denis Diderot, and William Gillette’s The Illusion of the First Time for the Actor. Study the great critics like Stark Young and H. T. Parker. When Harold Clurman was once accused of being an imitator of Stanislavski, he replied, “What’s wrong with that?” As an actor, you steal. The script is only an outline, so read novels for insights into the inner life of characters. Pick new, fresh material, not what other people do, and look for parts where you can steal the scene. There’s interesting material in foreign plays that aren’t being done here in America.

Because they’ll have to work in units on stage, I believe actors on all levels should train in groups or units together, with the teacher setting the sequence of exercises, taking full responsibility for instructing the actor when to go further, and evaluating if the exercise is properly done. Even though in the theater you may work with people with no or little experience, you must be able to maintain a standard of excellence for yourself. Training in a group gives you an opportunity to practice this.

Training, of course, is not a substitute for talent. Enrique Caruso was told not to waste his time, which shows us that we can’t always identify talent. The talent of the actor lies in their degree of sensitivity. For a human being, too much sensitivity is very difficult to live with. For an actor, there is no such thing as too much sensitivity. The deeper the sensitivity, the greater the possibility for expression. However, when feelings aren’t expressed and you can’t access and control them, your sensitivity runs counter to the craft of acting.

The ability to use your talent also depends on the degree to which you learn the technical procedures which our training emphasizes. Through our procedures, we gain control over our muscles, we learn to have control over our minds, and then the actor can start or stop their emotions at will without revealing the difficulties in doing this. The pianist plays all the same notes yet it’s the way he plays – that something only he adds – his particular awareness of what he’s doing. The more perfect the technique, the more we like it.

Someone starting off may have more talent than someone who has been at the Institute for years, but without training, talent will not grow. We give you the process and the skills to use your talent, but you have to actually do it. Nothing can move you unless you move yourself. You must commit to training every day throughout your career.

Lee Strasberg on relaxation and concentration

The heads and tails of the coin of acting are relaxing and concentrating. You relax in order to show that you have control of yourself. Then you concentrate to have control of the imaginary objects you wish to create. Other approaches to acting are immediately concerned with the scenes and their interpretation. Our preparation is contrary. Just because you know what to do in a scene, doesn’t mean you’re able to do it. To truthfully convey the ideas that the scene demands, we need the ability to relax at will and to apply inner concentration and awareness.

The purpose of the relaxation exercise is to eliminate fear, tension, and unnecessary energy, and to awaken every area of the body. Much of what stands in the actor’s way aren’t acting problems, but their personal issues that have nothing to do with a scene or its interpretation. Problems of expression arise from inhibited muscles and tension. Without relaxation and concentration the actor isn’t in a condition to make full use of his capacity.

Some people have the idea that what we want to do is “free” the actor. I don’t give a damn about freedom in that sense. Our work isn’t about freeing the actor. I want to put the actor in an artistic prison. The idea that expression is freedom is wrong. Expression means that you have something that you want to express in a way that is clear and true. This isn’t possible when you are tense.

A letting-go in each area of the body will allow you to become more responsive and to be sufficiently relaxed so whatever you’re working on for the scene or exercise can come through. When the body is relaxed, it’s able to move much more easily and with much less expenditure of effort; only then can you command each area of the body to do what you want it to do. To play the violin you have to check to see if it’s tuned by adjusting the pegs. If a piano isn’t properly tuned and you put your fingers on a key, the note comes out wrong. Tension is like a poorly tuned piano which isn’t tuned by just playing it. You must become aware of yourself and your body, like the double awareness of the writer who corrects his own punctuation.

As part of the training and general daily routine for their work, students should practice the relaxation and sense memory exercises fifteen minutes in the morning and fifteen minutes at night. When you’re preparing a specific exercise for class, practice relaxation every day for a half hour, then work on the assigned exercise for forty minutes or more. The best time to do an exercise outside of class is when you’re alone and at ease, enjoy yourself and let the exercise come to you. If you become frightened, stop immediately and go back to the relaxation exercise. There’s no real fear in merely being emotional, but I don’t want to encourage the sense of fear which may work against the effort you’re making.

Trust yourself and have faith and commitment in what you’re doing. Tell yourself, “There’s nothing I can’t do.”

Lee Strasberg on habits and conditioning

With relaxation and the exercises, we help the actor eliminate mannerisms that obscure the truth of expression. The basic habitual behavior of human beings leads to the habitual behavior of the actor. No approach to the actor’s problems – other than the Method – deals with habits, except in a purely external and mechanical way. Removing habits and involuntary nervous behavior is a new phase in the evolution of our work, which allows for a greater degree of development and control over your own instrument and helps actors to use, shape and apply what they possess.

Unconscious repetitive behavior is not anyone’s fault, but a product of our conditioning arising from lifestyle. We are impelled by habits, customs, and mannerisms which Stanislavski called “the stencils of life.” A child expresses everything because he’s born free. Little by little the child learns to control himself. The human being is initially expressive and then conditioning over the years runs counter to that expressiveness. Habit takes over.

By the time you come to study this work, you’ve developed a whole panorama and repertoire of patterns of behavior of which you’re literally unaware. These strongly ingrained habits result in our unconscious habitual behavior. With some people the head is always up in the air, like a searchlight. The head up indicates, “Let me get that clear.” The head tilted sideways indicates a watchful, “Please like me.”

When you tell the actor, “Stop that, you have a funny look on your face,” the actor is often surprised. “What do you mean, I have a funny look? I wasn’t thinking about what I was doing.” It’s very difficult to convey to the actor that he unconsciously does things, not deliberately, but as a result of unconscious behavior which may develop into mannerisms that can typecast the actor.

When habits are controlling you, they produce forms of expression that are conventional and clichéd. Swaying is the most habitual movement. We have verbal forms of expression which are simply conventional such as, “I beg your pardon,” and “May I …?” These behaviors have nothing to do with the feelings from the real experience; the natural bent towards expression is so inhibited, that the actor can’t express what he’s feeling. For acting, you must go further than the habits permit.

To deal with this problem, we have developed something which I believe is new. Relaxation and sense memory exercises deal with areas of the acting process and of the acting instrument which previously had evaded observation or had been treated purely externally. We try to eliminate the habits of non-expression and inhibitions created by conditioning so that when the impulse starts, it will lead to behavior different from the one to which you’re accustomed. Related to Pavlov’s work on the process of conditioning and the basic connection between the physical and the mental, we seek a conscious control of the faculties. A twenty-year habit may take as long as a year to break, but we believe everything that was conditioned can be reconditioned.

While other training may not hurt you, if it sets habits of behavior, it might. In our work, we want the body to become responsive so that the intensity of the experience the actor is creating – not habit – can emerge.

Relaxation exercise

Relaxing in the chair

In this exercise you’ll strengthen your will and the capacity to control your body doing certain simple things. To allow human behavior and habits to change, we need an accumulative degree of relaxation. Your goal is to relax and then control the muscles so that they’ll obey you. You must show that you can follow your own commands and develop freedom from habit. In the same way they must fit into any environment on the stage, actors must adjust to the chair.

Find a position in the chair that gives you a certain degree of comfort, a position in which you could, if you had to, go to sleep. There isn’t a right or wrong position. Let the chair hold you up. For example when you’re on a train or in a car and you want to sleep, you push yourself out somehow and try to settle in. You get the head back and you relax.

Breathe properly and easily or the muscles will get stuck. Let the body decompress, then create unity between the muscles and nerves, and maintain the body as a unit. Don’t fiddle around. This indicates an involuntary nervous expression which we don’t want. The human will is the strongest thing we know. Remain in control of your energy and your efforts.

The actor should be aware of every muscle in the body, so start to check each area separately by moving...