eBook - ePub

Mencius on the Mind

Experiments in Multiple Definition

I. A. Richards

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 192 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Mencius on the Mind

Experiments in Multiple Definition

I. A. Richards

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Long out of print, I. A. Richards's extraordinary 1932 foray into Chinese philosophy is worth reviving for its detached interpretation of the Chinese classics.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Mencius on the Mind un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Mencius on the Mind de I. A. Richards en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Ciencias sociales y Estudios étnicos. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

CHAPTER I

SOME PROBLEMS OF TRANSLATION

This is not strange, Ulysses I

The beauty that is borne here in the face

The bearer knows not, but commends itself

To other’s eyes: nor doth the eye itself—

That most pure spirit of sense—behold itself,

Not going from itself; but eye to eye oppos’d

Salutes each other with each other’s form;

For speculation turns not to itself

Till it hath travell’d and is mirror’d there

Where it may see itself. This is not strange at all !

Troilus and Cressida.

1. To a mind formed by modern Western training the interpretation of the Chinese Classics seems often an adventure among possibilities of thought and feeling rather than an encounter with facts. Perhaps this should be so at present with all ancient or foreign utterances. Perhaps we are only forced here to recognize an unescapable situation more frankly. However this may be, our first passage1 plunges us abruptly into the wild abyss of conjecture through which we have, in this undertaking, to make our way.

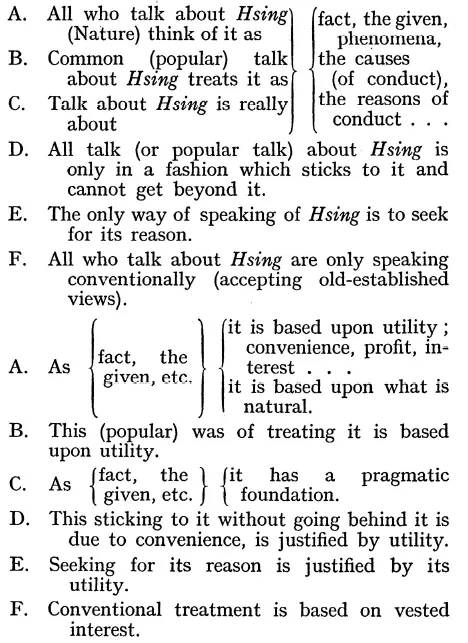

The following scheme of possibilities for our first two lines—one of the few methodological observations to be found in Mencius—indicates some of the readings which can, without undue straining, be given to them.

(If we only knew why we did treat it thus conventionally we should derive profit—understand the universe.)

Doubtless a more developed scholarship would be able to strike out some of these readings as inadmissible. But there is little doubt that it would be able to add others in their places. Even should the reading ‘Cause’—which stands in the text of the Appendix as perhaps the most plausible among them, being Mob. Tih’s use 2 of the term Ku—alone remain, we ought not to think that we have really made the passage unambiguous.

Apart from sophisticated philosophical uncertainty as to the meaning of ‘cause’, the word suffers from plenty of simpler sources of confusion. As Piaget well remarks, “There are as many types of causality as there are types or degrees of becoming aware of it. When the child first becomes conscious of the relation, this realization, just because it depends upon the needs and interests of the moment, is capable of assuming a number of different types, animistic causality, artificialistic, finalistic, mechanistic (by contact) or dynamic (force), etc. The list of types can never be considered complete.” 3

In attempting to choose one reading rather than another a very important consideration is soon forced upon us. As we shall see, Chinese thinking often gives no attention to distinctions which for Western minds are so traditional and so firmly established in thought and language, that we neither question them nor even become aware of them as distinctions. We receive and use them as though they belonged unconditionally to the constitution of things (or of thought). We forget that these distinctions have been made and maintained as part of one tradition of thinking; and that another tradition of thinking might neither find use for them nor (being committed to other courses) be able to admit them. And an analysis into separate alternative readings, such as the above, is likely (in a measure which we have no means at present of estimating) to misrepresent the original meaning, which may not correspond to any one of them but be nearer to a blend of several. But this blending metaphor will mislead, if we are dealing here with a meaning which includes, or treats as one, ingredients which for us may be distinct and separate, but were never analysed and then put together by the Chinese. And we should be rash to suppose that any blend we can achieve by abstraction and synthesis will really reproduce a thought which was not arrived at by these processes. We can come nearer to it perhaps by reversing our mental activity and going back from our defined and articulate abstractions to concrete imagining. This may, perhaps, be the very advice that Mencius is giving here to the wise ones. Not to work away arbitrarily at the problem of Nature (human and general) but to submit the mind to the fact so that the knowledge which it is in the mind’s nature to have of itself (and the rest of nature) may develop without interference. But the instance he gives of the success which the almanack-makers can attain tells against such an interpretation.

This ore-like character of Chinese thought including, together without distinction, elements we only have a use for when we have separated them—elements we can take together only as a result of high abstraction and with conscious philosophic daring—is illustrated in this passage both by Hsing (Nature) and Ku (Cause) and also in the structure of the sentences. Hsing stands both for Human Nature—the subject inquired about in most of these passages from Mencius—and for Nature in general. It is useful to have here at the beginning such a striking instance of the identification (or better, non-separation) of the two. The point will need further discussion, but we must from the outset realize that psychology and physics are not two separated studies for early Chinese thought (or for later); and that, however metaphysically abhorrent it may be to us, the mind and its objects are not set over against one another for Mencius, or (I understand) for any of his fellows.

This non-separation of human and external Nature—elaborated in Sung times, by Chucius (Chu Hsi), with Buddhistic speculations that seem to verge towards an idealism—may be connected with the fact that (except for Moh Tih and his followers) there seems to have been no problem of knowledge for Chinese thought. This absence of one of our prime Western problems may be an effect or a cause of the Hsing situation, or both may depend upon a deeper difference. The problems which for any one tradition are obtrusive—especially the more insoluble of them, and thus, it may seem, the more ‘important’—may often have arisen as a result of accident—grammatical or social. It is not certain, in spite of our historic preoccupation with the theory of knowledge, that the philosophical treatment of it has really, as yet, much advanced the development of science, for example; or that it is really as inevitable a problem as to us it seems. Its absence in what follows makes Mencius’ views on the mind the more interesting as a subject for comparative study.

Ku—with its senses of cause, reason, hold to, conviction, accepted of old, established, fact, datum, phenomenon—seems to stand for an idea which is none of these but out of which they may be developed through elaborated distinctions. Such a word as ‘because’ in ordinary unreflective English has a somewhat similar width and vagueness of reference. Or ‘grounds’, if we let its metaphor come to life, may give us something like its undifferentiated seeming simplicity.

But these two uncertain words by no means account for all the ambiguity of the passage. In the West we are so accustomed to explicit sentence forms that we expect this kind of vagueness only at certain specific points in discourse—at words which are recognized to be indefinite in meaning. We are ready for a good deal of vagueness there. But a sentence shocks us whose whole structure has the same kind of indefiniteness. It appears to be a mystification on a much grander scale. Here, over and above all uncertainty as to the meaning of the terms, a major uncertainty as to the form and intention of the sentence has to be reckoned with. Is Mencius enunciating his own view of Hsing ? Commenting upon the popular view ? Correcting it, accepting it under qualification, or contrasting it with that of the gentleman ? (Cf. p. 40.)4 Is he perhaps remarking that the common view over-simplifies the cause of conduct fatalistically; or that it takes what we should call a hypothesis for a fact, or the other way about; or that it does not go behind Hsing to look for reasons; or that is is merely conventional; or that it does not recognize that it is merely a useful convention ? These and other similar questions are not to be settled by inspection of the syntax of the passage. They are to be settled, if at all, only by the influence on our interpretation of other passages—many of them almost equally indefinite by themselves. The symbol situation thus presented has a special interest. It is the extreme case which shows us—better than the average case—how interpretation of all language which is not strictly governed by an explicit logic proceeds. And more of our language than we suppose is of this kind. Perhaps apart from the language of mathematics we have none that is not. Certainly poetry uses this method—the indirectly controlled guess—for most of its purposes; and when poetry is highly condensed as, for example, it often is in Shakespeare and in much modern writing, the degree of implicitness may be as high as in any passage of Mencius. Compare Macbeth (I, vii):—

But here, upon this bank or shoal of time,

We’d jump the life to come. …

Vaulting ambition which o’er leaps itself

And falls on the other.

The parallel with such poetry is, I think, illuminating here, and we must often be doubtful whether Mencius (still more Confucius at times, and Tzu Ssu, the author of the Chung Yung) should not primarily be regarded as a poet. His aims seem often to be those of poetry rather than of prose philosophy. Be this as it may, his method—even when his aim is severely prosaic—is frequently the method of condensed poetry. If we wished for a short description of the difference between Confucian philosophic method and, shall we say, Kantian, we could hardly do better than to say that the latter endeavours to use an explicit logic and the former an indicated guess.

It may be relevant also to note that in the traditional reading of the text, even for the purposes of exposition, scholars of the old school give it a very pronounced roll amounting almost to a chant. This, and the fact that from early times until yesterday it has been learnt by heart before any attempt to understand is made, should be borne in mind. Psychologically the consequences of this last may go to the roots.

For this learning-by-heart gave the text a general meaning and sanction based on the duration of its familiarity. Moreover, the text became for all scholars a common schema with reference to which the gestures of mutual understanding could be performed.

Another comparison may help to make this indefinite use of language seem less wanton or jejune and more interesting. Such a list of alternative readings as the above bears at points a resemblance to the successive attempts that a speaker will sometimes make to convey a thought which does not fit any ready formulation. He may intimate as he switches (with an ‘or rather’ or a ‘perhaps I ought to say’) over from one statement to another, that he is ‘developing’ his thought. Those with a taste for clear, precise views (itself a result of special training) will accuse him of not knowing what he wants to say, or of having really no thought yet to utter. But there is another possibility—that a thought is present whose structure and content are not suited to available formulations, that these successive, perhaps incompatible, statements partly represent, partly misrepresent, an idea independent of them which none the less has its own order and coherent reference.

This is not a possibility to be conceded too freely since mere muddle-mindedness is probably much commoner than genuine inexpressible thought. But often with Mencius the successive translations that come up—some not ‘making sense’, some irreconcilable, none seeming adequate—do seem to indicate that his terse utterances shroud and figure forth such ideas. Though they have passed in one interpretation or another into the fabric of Chinese mentality to a degree which has perhaps no parallel in the West, they remain, some of them, highly mysterious, even to the best equipped Chinese scholars. So our problem is not merely one of translation, but of interpretation and understanding. It is well to remember this fact, that we often are not dealing with expressions whose meaning, to good Chinese scholars, can be said to be either settled or clear. It adds a spice of the excitement of discovery to what might seem to be a mere struggle with a linguistic disaccord.

The attempt to express ancient Chinese thinking with English as an instrument would be worth making if it did no more than demonstrate the disaccord between the two methods of thought and language. It has, however, a practical urgency as well as a theoretic interest. The number of persons equipped to-day with a purely Chinese scholarship is rapidly diminishing. Before long there will be nobody studying Mencius into whose mind philosophical and other ideas and methods of modern Western origin have not made their way. Western notions are penetrating steadily into Chinese, and the Chinese scholar of the near future will not be intellectually much nearer Mencius than any Western pupil of Aristotle and Kant. Unless the thinking which has been fundamental to historic China can somehow be explained in Western terms it seems inevitably doomed to oblivion. In a sense, of course, it is lost already, together with all the thought of the past. No one will again think the thoughts of Mencius. Contemporary mentality comes like a distorting medium between. But we can at least try to investigate the laws of refraction of this medium with the hope of introducing some corrections and with a better hope of discovering something further about our own contemporary mentality, its characteristic forms and limits.

Similar distortions have, of course, been introduced at many points in Chinese history. Perhaps in Han times the official doctrines of Mencius were already far removed from his own. Certainly with the Sung School the influence of Buddhist metaphysics and the passion for system of the Sung schoolmen made a new thing of them. But the changes occurring now go deeper and spread wider, and Chinese studies in the future, even for the Chinese, have a new practical problem to face—that of devising a technique which will take deliberate account of these new differences in the medium through which the inquirer himself must approach.

2. Reciprocally the attempt to thi...