![]()

PART I

The Principles

![]()

1

What is Movement?

Keith established Movement as a unique discipline central to actor training. His influence on Australian theatre will continue for many years to come.

JOHN CLARK AND ELIZABETH BUTCHER

What’s the big deal?

We all move, so what is the big deal? We move when we want to. Get where we need to go without thinking much about it. We have little regard for how awkwardly or gracelessly we do it. So why get into a state about it?

We are constantly speaking a movement language—the language of our own individual life—that is transparently readable. In ordinary life, we picked up this language in so informal a fashion that although we can make ourselves reasonably understood, we speak it with the limited effectiveness of a person who is using a language but is ignorant of its spelling and grammar.

Movement is both how we move and what moves us. Movement is the look in our eyes, the tensions and the tone in our muscles, our breathing, our thinking, our longings and fears. Movement Studies has equal concern for the inner and the outer aspects, with each clarifying the other, enriching the connections and, like all knowledge, extending the imaginative and artistic horizons. There are psychological implications underlying all the movements we make and all of the theories, concepts and analytical principles that are currently in practice: and there are possibilities and manifestations of movement to be investigated in the actor’s search for the revelation of psychological truth and inner richness.

What is Movement?

Movement is a big subject and demands a big definition. But precisely because its range is so wide, it is difficult to give it a simple definition. Movement is capable of the finest shades of everything, from delicacy and ecstasy to grossness and abstraction. Its implications are so essential to everything we do that it is vital to the whole organic art and craft of performance.

‘Movement for actors’ can be a vague and threatening term to people who don’t consider themselves physically adept or experienced. Many find exercise boring and may have spent a lifetime avoiding it. Others may be prejudiced against physical activity of any kind, as a result of accident or humiliation in the playground or on the sports field. These are the ones who imagine the study of Movement will expose an even more depressing array of physical and expressive deficiencies than those of which they are too well aware. For others again, the idea of Movement will have been coloured by a damaged self-image composed of a nasty combination of former criticisms, failures, poor or insensitive teaching, cruel taunts and a dislike of their own body, looks and general physicality.

The popular perception is that Movement training is mostly a matter of teaching actors to faint and fall down stairs, dance a little, bow and curtsy elegantly, be capable of some mime and stage fighting. People think that the word dance is a helpful one, and they think dance and Movement are essentially the same thing. Unfortunately that is not the case. When an actor acts well, the physicalisation of the actor’s inner and outer life is so seamless, truthful and discreet that it all looks as though movement just happens. A virtuoso technique can disguise the effort. When an actor acts less well, when the body tells lies and fails to find ease and truth, the significance of Movement becomes clear.

Sadly, relatively few people, even actors themselves, fully appreciate the potential of the study of Movement. Top directors, and company administrators for drama, opera and film, see value in dramaturgs and voice consultants but fail to involve a Movement specialist in a production except to deal with the dance sequence or the sword fight. In doing so, they fail to appreciate the enormous contribution an expert in Movement can bring to a production, enriching the actors’ choices, setting the style of the piece and its concept, refining the atmospheres and creating the dramatic visualisation of the whole production.

We moved before we painted, carved, danced or sang. And yet, probably because our movement is so basic to us and so bound up with ordinariness and practicality, we have taken a long time to see the art in it and the beauty that comes from its truthfulness. The component building blocks of all the principal art forms have been set for centuries. These elements have provided a basis for criticism, comparison and, importantly, become the groundwork for practical approaches to the teaching of that art form.

Music in Western civilisations, for example, has long been defined as consisting of melody, harmony, rhythm, form, instrumental colour and dynamics. These are perfect bases for study, for evaluation, for developing teaching techniques for composition and performance and for creating the notation system that preserves the music of every period. For thousands of years, in hundreds of cultures, sculpture has been defined as space, perspective, proportion, texture and composition. Around the art form a theory and a set of practices and principles have developed that heighten the appreciation of it, and build traditions that can be taught to each new generation of sculptors. In painting, the elements of colour, design, perspective, tone and form have been explored to the advantage of artists, scholars, historians, critics, teachers and their students.

Think now of such essentials to the study of Movement as motive, instinct, intention, inspiration, time, energy, emotion and temperament, and it becomes clear how intangible these are until they are examined by the results they produce.

François Delsarte, (1811–1871)* made a brave attempt at a philosophy of Movement. He claimed that movement could be classified into three distinct categories: mental (the head), emotional (the trunk) and physical (the limbs); and his three laws: of opposition, natural succession and harmonic positions, created considerable interest among his contemporaries. He sought to make a complete analysis of the gestures and movements of the human body and attempted to formulate laws of speech and gesture that would be as precise as mathematical principles. For him, the artist’s aim should be to move, interest and persuade; and he considered that nothing could be more deplorable than a gesture without motive.† Though his work is of little influence today, he provoked fresh thought, especially among the early wave of Central European modern dancers, including Mary Wigman, Kurt Jooss and Laban himself.

The genius who saw through all the blurring layers was Rudolf Laban (1879–1958). His discoveries changed everything. He has influenced dance and choreography, drama production and drama training, therapy through movement, the notating of dance and movement works, the analysis of Movement qualities in the human and natural spheres and much more. That his conclusions burst onto the European arts scene so long after all the other art forms had been formulated, accounts for the ongoing struggle for academic acceptance that dance and theatre educationalists continue to face.

Gertrud Bodenwieser (1890–1959) was one of those pioneers who readily acknowledged his contribution to her own thinking, as she acknowledged the work of another historic figure in the history of movement theorists, Emile Jacques–Dalcroze (1865–1959). Dalcroze set out to investigate new ways of teaching music, and particularly rhythm, which he claimed to be the basis of art. His system involved translating sound into movement, and in doing so he introduced the concepts of space and speed, timing, levels and force, to the world of movement and dance. He also believed that the study of gymnastics, musical theory and rhythm was fundamentally important for physical and moral balance.

The two categories of Movement

Movement ranges from absolute stillness, through the simplest of natural movements to feats of skill that lie beyond the capacity of any but the rarest of individuals. However, there is a clear twofold division. Helen Cameron and Diana Kendall in their book Kinetic Sensory Studies distinguish the first category as Survival Movement.* The second can be defined as Learned Skills and Practices.

Survival Movement

Survival Movement has to do with the basics, and refinements, of all the natural and practical movement that evolution has deemed necessary. It includes obvious things like mastering the features and dimensions of our own structure. It encompasses not only all the most basic activities—walking, running, grasping, climbing, pulling, pushing and so on—but also communicating with others, satisfying our needs and pleasures, and adapting to the varying conditions of existence, such as hunting, gathering and building. It is a treasure trove.

The word ‘movement’ immediately indicates its concern with doing. Doing anything—from the subtlest involvement of the small muscle groups to the most violent and extravagant response to a situation. Doing nothing is a positive aspect of moving. Whatever you are doing right now, whatever you have just been doing, and whatever you do next, either planned or unforeseen, is the stuff of Movement. Whether your movement develops from within your mood, need or will, or is a reaction to an external stimulus, it is all part of the study.

Even the most ordinary activities, such as how you sit, stand, walk, gesture, eat, drink, scratch, fix your hair, turn the page, frown, smile, chew your fingernail, carry your head, wear your clothes, are movements telling the moment by moment story of your nature and your life as you live it. The angles of your body, your distance from your partner, how often you blink, are all revealing details. More significant, in Movement terms, is how these activities change and adjust to each new inner impulse and each outer change of circumstance. A big implication here for the actor is how you might adjust, modify, and refine movement to better effect.

Learned skills and practices

The second category includes whatever skills and practices humans, over time and within their special circumstances, have invented and developed. Man’s ingenuity and capacity for play and expression have seen to it that there are a myriad of these devised skills and practices. They include all dance forms, circus skills, the many types of sports, yoga and the various martial arts. These skills require focus, coordination, timing, strength and agility, often stamina and endurance. They are consciously performed actions that require repetition and practice to become proficient and can reach unbelievably high standards of complexity, artificiality and sophistication.

For ease, I define everything concerning survival movement as Movement with a capital M, and therefore the subject of Movement Studies. All the devised forms are just other ways to move.

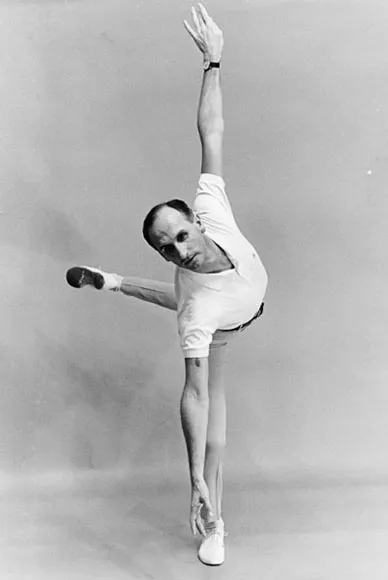

Keith, studio shot 1974

Applications of Movement

Reconstructing, in a performing situation, the inner and outer truth of even the least complicated sequence of natural activity, is fiendishly difficult. If, as an actor, all you ever performed was a character exactly like yourself, it would still be difficult to present that character with naturalness and honesty in front of an audience or camera. It would mean being free of all your inhibitions and secure in awareness of your personal reactions, mannerisms, and the physical manifestations of your emotional and psychological states. To reproduce it in all its honesty we need the capacity to analyse what we do. As an actor, however, you are habitually faced with representing a variety of characters. So you need to be as wise and sensitive about others, as you are about yourself. The study of Movement allows an acting technique that is grounded in the analysis of your own behaviour patterns, psychological states and the dictates of your temperament, yet allows the ability to experiment with the underlying principles of acting.

As a physical and practical study, Movement should include, but not be confined to, the mechanical and the technical considerations of a body in motion. Its ultimate forms are disciplined expressiveness, transformational ability and insightful human behaviour. Look those up in your dictionary and the subject of Movement, in all its glory and responsibility, will be revealed.

Movement as evidence of the internal world

Concern for the naturalistic detail of behavioural patterns, and the reproduction of realism in stage movement, however, has its counterbalance. ‘Truth’ is not necessarily best expressed by naturalistic means. The stage, often more so than film and television, can make its strongest and most telling statements by departure from the natural and the literal into degrees of stylisation, enlargement, distortion, symbolism and abstraction that can enrich immeasurably the presentation of character and narrative, and the depiction of powerful atmospheres. The simply personal can be made universal when these devices are employed, but only when actors are capable of heightening the truth of their inner states in the playing of them. This must not mean that the actor is leaving truth further and further behind as they move deeper into an abstracted or stylised state. It should be that they are entering deeper into the essence of that truth, intensifying it as they go. This presents many an actor with a considerable challenge. For instance, young actors who can comfortably represent the truth of contemporary characters and situations, find the truth of an unfamiliar time and place, with its own perspectives, protocol, etiquette and conventions, an inhibition to making artistic judgment. It requires the actor to be both brave and at ease when they are given the challenge of exploring extremes of eccentricity, grandeur, stillness, vulnerability and abstracted states.

We cannot see a thought but movement can give evidence, not only of the process of thinking but of the nature of that thought. We cannot directly see an emotion, or such physical states as pain and hunger, or such characteristics as greed or shyness, but we can recognise, through the evidence of movement, precise and precious detail of all these experiences as well as the changing degrees of their intensity. It is movement, perhaps as discreet as a pause in one’s breathing or an introverted focus of the eye, that reveals all these states.

Three points to consider in this regard are of great importance:

• | The constant change of thought and feeling as we succeed or fail to achieve what we want; |

• | The very moments of change from one degree of feeling to another, and from one state of thinking to another; |

• | The degree to which we either reveal or conceal our motives and their accompanying emotional states. |

All of these considerations involve some of the subtlest aspects of movement for the actor. The capacity to manifest these in performance is the mark of our finest actors.

By the first of these points, I refer to the need for the actor to realise that though their state of feeling or thinking—for example anger over a failure to get what they want from another person—may last for several minutes, ...