The Chicago Flood

On Monday, April 13, 1992, downtown Chicago came to a standstill. The Chicago River was flooding freight tunnels that had been dug underneath the city in the early part of the twentieth century. Water was seeping into the basements of office buildings in the city’s financial district, with its stock exchange, commodities market, and Federal Reserve, and into the upscale retail area, where department stores such as Marshall Field’s (now Macy’s), Burberry, and Neiman Marcus are located. All buildings in the area were evacuated and traffic halted. Downtown Chicago became a ghost town for three days. The city took weeks to pump all the water out. The cost in closed business and ruined inventory ran to approximately $1.25 billion.

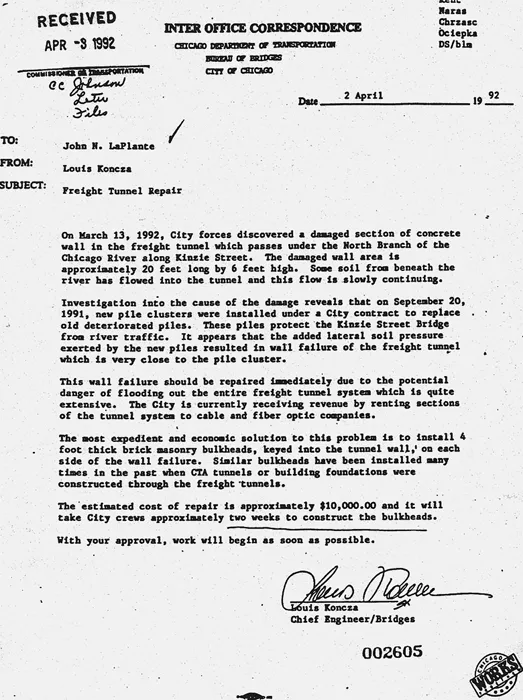

The cause of the flood was a leak in the wall of one of the tunnels abutting the river. Several weeks earlier Louis Koncza, the chief engineer for the Bureau of Bridges in the city’s Department of Transportation (DOT), had sent a memo to John LaPlante, acting DOT Commissioner, notifying him of the leak and requesting permission to repair the walls. But the wall wasn’t repaired before the leak became a flood. Miscommunication between Koncza and LaPlante was one of the reasons.

Beneath the city of Chicago lies a labyrinth of tunnels that were created at the beginning of the twentieth century. The tunnels allowed small train cars to carry coal from the barges that came down Lake Michigan to the basements of the city’s buildings above. With the change from coal to oil and gas in the latter part of the twentieth century, the city began to lease these tunnels to cable companies for stringing their cables. In January, four months before the flood, a cable company employee went into the tunnel near the Kinzie Street Bridge to study the situation prior to the company’s installing the wire. The employee found water and soil leaking into the tunnel and notified his company, which, in turn, notified the city. A city engineer was sent to investigate but couldn’t find a parking place. It took over a month before another employee was sent to check out the report. This time he found a parking place. However, by now the small leak had become a large leak, and the employee found so much damage to the wall that he felt it was unsafe to enter the tunnel. He took photographs and returned. After several meetings to determine what should be done and to estimate the cost for the repair, Louis Koncza was charged with writing a memorandum to the manager of his division, John LaPlante, requesting permission to repair the tunnel (Figure 1.1).4

The memo was typed on a form for interoffice correspondence that included in the upper right-hand corner the names of the people other than Koncza to whom documents in the DOT were routinely distributed. These people were often involved with some aspect of a project. In this case, one of the men, Ociepka, had been the project manager for the installation of new pile clusters around the Kinzie Street Bridge, where the leak had begun. Apparently, during the installation, one of the piles had hit the tunnel wall, puncturing it. Another reader, Chrasc, worked under Koncza as his coordinating engineer and would be responsible for coordinating the repair project. Koncza penciled in at the upper left-hand corner the names of three additional people who needed to be informed of the repair work for the leak. Many of these people were eventually fired by then-mayor Richard Daley, Sr.

Koncza, who was busy and had several other problems demanding attention, did not spend much time planning the memo. Instead he wrote it using the same organizational structure that he had used in writing many previous memoranda. He was very much aware of the economic aspect of the tunnel, which brought rental fees to the city, and alluded to this, implying that if the tunnel was not fixed, the city might lose its fees. He did not take much time to read it over and make revisions, other than checking that the facts were correct and then proofreading it for grammatical or spelling errors. On April 2 Koncza sent the memo through interoffice mail to his supervisor rather than delivering it in person as was the convention for matters requiring immediate action.

LaPlante received the memorandum along with a large batch of other interoffice mail the following day, April 3. He constantly received memos describing construction problems and requesting approval to have them repaired. Because this one had been transmitted by interoffice mail rather than in person, it did not appear different from the others.5

When LaPlante received the memo in the pile of mail delivered to his desk that Friday afternoon, he simply gathered it along with the entire pile and took it home. On Sunday afternoon, he read through the stack of memos, including the one on the Kinzie Street Bridge.

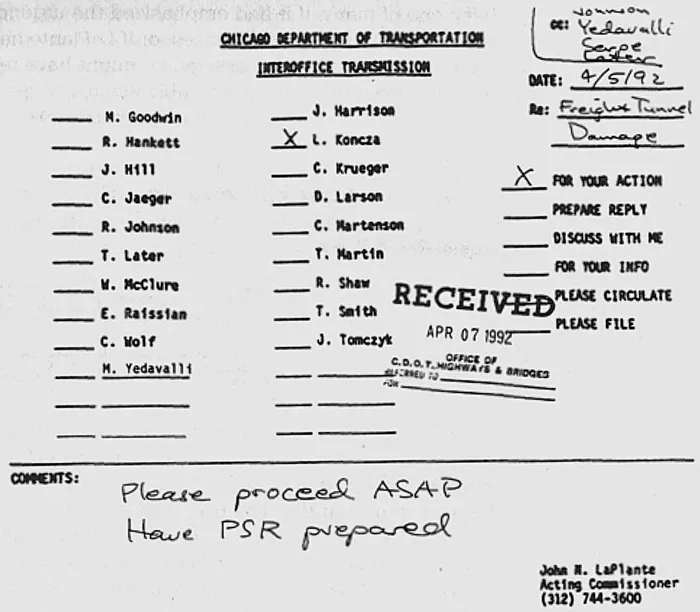

LaPlante had only recently been appointed to the position in an acting capacity. He was not an engineer but a financial manager. He had little knowledge about the problem discussed in the memo; he wasn’t even sure where the Kinzie Street Bridge was. Having no secretary or typewriter available (this was BC [Before Computers]), he handwrote his response on one of his memorandum forms, approving the repair. Recognizing that the mayor was up for reelection (the political context), he recommended that the repair job be put up for bid. (A PSR [project specification report] is a form for putting out a bid.) He also penciled in the names of several other readers who needed to be kept informed of the project (Figure 1.2).

Returning to work on Monday, LaPlante placed the memo in interoffice mail. It was delivered on Thursday, as the stamp in the upper left-hand corner indicates. It took three more days for Koncza to respond to LaPlante’s orders and send a memo requesting that the PSR be processed.

The PSR was prepared and put out for bid. Two bids came in by April 10. Both were over $70,000, approximately, $60,000 over t...