eBook - ePub

Inside Campaigns

Elections through the Eyes of Political Professionals

William J. Feltus, Kenneth M. Goldstein, Matthew J. (Jeremy) Dallek

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 368 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Inside Campaigns

Elections through the Eyes of Political Professionals

William J. Feltus, Kenneth M. Goldstein, Matthew J. (Jeremy) Dallek

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Take your students on a journey into the world of campaign managers. Powered by scores of interviews and surveys of political professionals, the book considers the purpose, potency, and poetry of modern political campaigns in the US.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Inside Campaigns un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Inside Campaigns de William J. Feltus, Kenneth M. Goldstein, Matthew J. (Jeremy) Dallek en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Politics & International Relations y Political Campaigns & Elections. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1 Losing and Winning The Craft and Science of Political Campaigns

There are three people that I want to acknowledge tonight because if it wasn’t for them, we would not be here . . . whenever the history is written about Alabama politics, remember those names, Giles Perkins, Doug Turner and Joe Trippi.—Democratic US senator-elect Doug Jones credited his upset victory to his campaign managers in a nationally televised victory speech on the evening of December 12, 2017.1

Political campaigns are like new restaurants: Most of them will fail. Of the more than 140 campaign managers we interviewed for this book, nearly all had lost elections—and many of them more than once. Even the most experienced and successful campaign manager can lose unexpectedly and even spectacularly.

Consider the case of a campaign manager we will call “TW.” For three decades, he managed his candidate—his client and his best friend—rising from the New York legislature, to the governor’s mansion, and on to the US Senate.2 Along the way, TW had worked for other candidates who were nominated for or won the presidency.3 TW’s skills as a campaign manager had earned him national renown and a very comfortable living. He was the undisputed American political wizard behind the curtain.

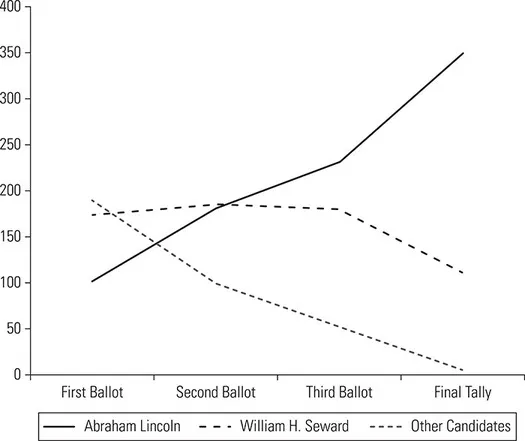

Now at the peak of his craft, TW was in Chicago at the Republican Party’s nominating convention. His client of thirty years was the front-runner to win the nomination. TW was so certain of the result that he had sent his candidate out of the country on a preconvention tour of European capitals. The news media and the buzz on the convention floor held that TW’s candidate was assured the nomination. But when the voting finally got under way, TW and his candidate were stunned when they led the first roll call with only 37 percent of the delegates and were forced into a second ballot.4 The aura of inevitability so carefully cultivated with the media and party leaders began to dissipate, and there was no Plan B. On the third ballot, a dark-horse candidate wrested the nomination from TW’s grasp.5 The political wizard was no more.

The dark-horse candidate was Abraham Lincoln, and the year was 1860 (see Figure 1.1).6 It was only the second national convention for the Republican Party, and Senator William H. Seward of New York had been expected to emerge with the nomination. Seward’s manager was fellow New Yorker Thurlow Weed, who had earlier worked on the presidential campaigns of William Henry Harrison (1840), Henry Clay (1844), Zachary Taylor (1848), Winfield Scott (1852), and John Charles Fremont (1856).

Weed was a national figure, but even the most successful managers rarely achieve that status. This book is not about celebrity campaign managers and consultants who achieve notoriety on presidential campaigns—although we’ve interviewed a number of those. Instead, we aggregate the insights of a wide swath of people who have run winning and losing races for both parties and at all levels of politics—from the courthouse to the White House.

Figure 1.1 Presidential Balloting at the 1860 Republican National Convention, Chicago, Illinois

Source: Data from the Proceedings of the Republican National Convention held in Chicago, May 16, 17, and 18, 1860, https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofrep00repulala.

The managers we heard from share a number of common traits and skills, including the ability to play multiple roles in the pursuit of victory on election day. And, in this book, we examine the many responsibilities, decisions, and experiences that managers can—although don’t always—use to drive the success or failure of campaigns. This is not a how-to handbook but instead the collected insights from scores of political professionals, supplemented with our own knowledge of campaign mechanics and core scholarly findings about the fundamental factors that influence campaigns and elections in America. Through this synthesis, we can gain not only a greater understanding of what managers do and the array of roles they play but also the workings of the most important mechanism in a democracy—free and fair elections.

A Tale of Two Managers

The science and mechanics of political campaigns have changed since Weed’s heyday. Yet many of Weed’s skills remain essential in twenty-first-century electoral politics. For example, compare Weed to President Barack Obama’s adviser David Axelrod, one of today’s best-known political strategists.

Before entering politics, both Weed7 and Axelrod8 worked in the newspaper business where they learned the degree to which the news media can shape public opinion. During Weed’s career, the printed newspaper was king. In his media world, all newspapers were partisan organs like today’s Fox News Channel, Drudge Report, MSNBC, or the Huffington Post. With almost no formal schooling, Weed started out as a teenage typesetter and press operator for the Albany Register in the state capital.9 There, he learned the ways of the political machine that ran the state legislature and government offices of New York. Much like today’s political bloggers, Weed launched his own Evening Journal in 1830, using the paper and his bylined column to first support the Anti-Mason Party, then the Whig Party, before finally joining the newly formed Republican Party in 1856 in opposition to the Southern-dominated Democratic Party.10

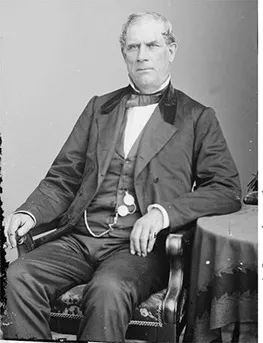

Thurlow Weed was stunned along with the rest of the political establishment when his candidate, Senator William H. Seward, was upset at the 1860 Republican convention by a dark-horse member of Congress named Abraham Lincoln.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Brady-Handy Photograph Collection.

Senator Seward himself said, “Weed is Seward, and Seward is Weed, each approves of what the other says or does.”11 No candidate today would publicly say such a thing, but trust and mutual dependence between candidate and manager remains essential in politics. Even after the wrenching 1860 defeat in Chicago, Seward reached out to console Weed and sustain their relationship. “You have my unbounded gratitude for this last [campaign], as for the whole life of efforts in my behalf. I wish that I was sure that your sense of disappointment is as light as my own,” Seward wrote in a letter to Weed after their 1860 defeat in Chicago.12

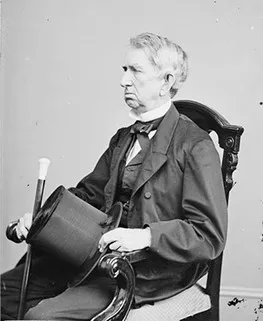

Thurlow Weed’s client, Senator William H. Seward.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Brady-Handy Photograph Collection.

After losing the 1860 Republican nomination to Abraham Lincoln, Seward and Weed both became actively involved in Lincoln’s general election campaign. Seward went on to serve as Lincoln’s secretary of state.13 Weed also continued to be politically involved. In fact, Lincoln asked for Weed’s help in supporting Republicans in the 1862 congressional elections.14

Like Weed, Axelrod’s first job was at a newspaper. After graduating from the University of Chicago in 1977, Axelrod worked for the Chicago Tribune, becoming the paper’s youngest political writer before leaving journalism and joining the 1984 Illinois campaign of Democratic candidate Paul Simon for the US Senate.15 After starting as communications director, Axelrod eventually was named campaign manager. The underdog Simon went on to upset the popular three-term Republican incumbent, Senator Charles Percy, in a year when Republican Ronald Reagan carried Illinois and every other state except Minnesota. In the same state where Weed lost his final campaign, Axelrod won his first.

Journalism made Axelrod a better manager and strategist, he says now. “Because so much of what modern campaigns involve is about message and communications, having been a journalist was helpful to me.” He added, “When I was parachuted into campaigns as a reporter, I went in with some presumptions. But to me the job was to get on the ground and really understand what the political terrain was . . . to figure out what people were thinking, what voters were thinking. Those skills were very helpful as a strategist and as a manager.”16

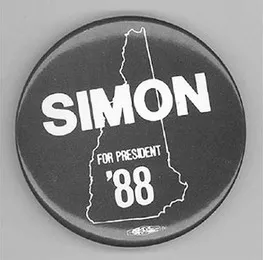

David Axelrod lost his first presidential campaign. He is pictured here in 1988 when his client, Senator Paul Simon, finished a surprisingly strong second in the Iowa caucuses but faltered in the New Hampshire primary.

NBC Chicago

Ron Wade Buttons

Those skills came up short in 1988 when Axelrod, now playing the role of campaign consultant instead of manager, was the chief strategist for Senator Paul Simon’s (D-IL) campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination. Simon’s campaign gained early momentum with a stronger than expected second-place finish in Iowa, the first round of the nomination contest. But, in the next round, Simon lacked the cash to put Axelrod’s television ads on the air in New Hampshire, which includes the expensive Boston media market. Simon came in third in the Granite State behind eventual nominee Governor Michael Dukakis of neighboring Massachusetts.

Axelrod also lost with his next presidential candidate, Senator John Edwards (D-NC). It wasn’t until the third try that an Axelrod client made it to the White House. “You have to choose your candidates well . . . . But you also have to go in knowing that none of that guarantees victory in a very dynamic process in which so many factors can impact on the outcome,” said Axelrod. “You’re never as smart as you look when you win, and never as dumb as you look when you lose.”17

Learning and Experimenting

After President Obama’s 2012 campaign outmaneuvered challenger Mitt Romney, the postelection coverage and conversation was dominated by talk of how much more sophisticated Democrats were with modern campaign mechanics and tools like big-data analytics. And, when it came to the use of the Internet, just about everybody thought the Democ...