eBook - ePub

Mourning and Mysticism in First World War Literature and Beyond

Grappling with Ghosts

George M. Johnson

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Mourning and Mysticism in First World War Literature and Beyond

Grappling with Ghosts

George M. Johnson

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This book traces how iconic writers - including Arthur Conan Doyle, J.M. Barrie, Rudyard Kipling, Virginia Woolf, Wilfred Owen, and Aldous Huxley - shaped their response to the loss of loved ones in the First World War through their embrace of mysticism.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Mourning and Mysticism in First World War Literature and Beyond un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Mourning and Mysticism in First World War Literature and Beyond de George M. Johnson en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Storia y Storia militare e marittima. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

StoriaCategoría

Storia militare e marittima1

F. W. H. Myers: Loss and the Obsessive Study of Survival

“I know no man who seems to have lived more consistently in a sort of rapture of thought, without weary or discontented interludes, but in an impassioned ecstasy of sweetness. In this he was a mystic, and his joyful serenity of mind is just what one finds in the lives of mystics.”

A. C. Benson “Frederic Myers” 183

“The reader need not suppose that I expect his admiration. But if he on his part be psychologically minded, he will prefer that idiosyncrasy should not be concealed. If he is to be interested at all, it must be in the spectacle of a man of sensuous and emotional temperament, urged and driven by his own personal passion into undertaking a scientific enterprise, which aims at the common weal of men … what has been accomplished did in fact demand, – among many nobler qualities contributed by better men, – that importunate and overmastering impulse which none can more fiercely feel than I.”

Frederic Myers, introduction to “Fragments of Inner Life” 2

The young boy sits on a wooden chair in a sparsely furnished rectory, his mother presiding over him. The boy looks up, bible in hand, and asks his mummy whether bad people go straight to hell. His mother purses her lips and looks away before telling him that evil people might be destroyed at death. His lip quivers as he asks whether they would have the same fate as the mole he had seen crushed by a cartwheel, and she reluctantly says perhaps. Tears well up and he staggers to his feet, as if reeling from shock. His mother’s forehead creases, but before she can respond he has darted out the French window to the garden. She calls out Freddie, but he takes no notice, instead running to his favorite spot, under a great clump and tangle of blush roses. There he sobs, and through his tears looks down on the black pool of Bassenthwaite Lake and then up towards Skiddaw mountain, its shoulders and peak cloaked by cloud. He becomes entranced by the clouds’ movements until the peak emerges, as high as heaven, and his tears subside.

Some days later, his mother gently pushes him forward into the sickroom, where the pale and shrunken figure of his father lies, barely recognizable from just a few months before. Then, his father had paced in the study, declaiming Virgil and emphasizing the stresses with his hand. Freddie flushes, remembering how his father had scolded him for not having done his exercises as well as he might have, and he wonders whether this neglect has helped bring on his father’s sudden illness. Freddie sits beside his mother, holding her hand, as she with her other hand holds her husband’s until it grows cold, and the breath ceases. His mother tries to control her crying, and Freddie places a kiss on her cheek. In the days that follow, he appears at just the right moments, when his mother is borne down by her tragedy, head in her hands, and he caresses her or reads from a little book of Christian Meditations. One time, when overpowered with grief, she murmurs “there can never be joy again.” Freddie says earnestly, “You know, God can do everything, and He might give us, just once, such a vision of him as should make us happy all our lives after.”

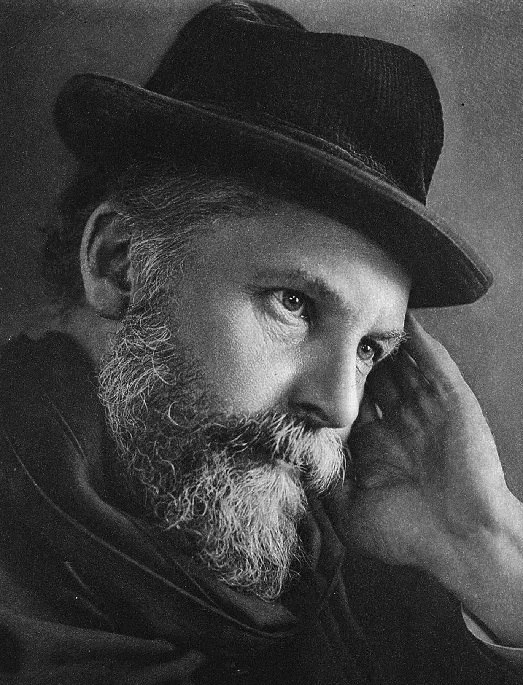

Young Freddie grew up to be Frederic W. H. Myers (Illustration 1.1), and the scenes I have reconstructed here capture something of the most critical moments of his early childhood. Myers recounts that he felt “the first horror of a death without resurrection” when he saw a dead mole before age six, and how his “brain reeled under the shock” of being told by his mother that a soul might be annihilated. In a journal, his mother recounted his sensitivity to the death of an unnamed baby cousin and to another called Harry. She also noted how much of a comfort he was to her in her “deep sorrow” after the loss of her husband (Gauld 43). Those losses, particularly of Myers’s father, which also entailed the loss of his beloved early environment, combined with his mother’s emotional overinvestment in her eldest son, provide the sources for his obsessional quest to prove the survival of personality beyond death. Myers possessed “a sensuous and emotional temperament,” as he himself realized, and he learned early on to channel some of this emotion into poetry, increasingly so after he experienced the greatest loss of his adult life, the suicide of his cousin Annie Marshall, for whom he had developed an intense platonic love. From this point on, his response to loss was increasingly avoidant-resistant, as his unresolved mourning and preoccupation with death was directed into his gargantuan labors at psychical research and the dynamic psychology that he constructed. To observers, such as A. C. Benson quoted in the epigraph, he could appear to be “a mystic,” living “consistently in a sort of rapture of thought” (183), but his wife, Eveleen was less than thrilled with this detachment.

Illustration 1.1 Frederic Myers

From the 1880s Myers developed his theory of the subliminal self, with its emphasis on the limitless potential of the psyche, and he also probed many other psychical phenomena, including telepathy, automatic writing, and crisis apparitions, through publications of the Society for Psychical Research, which he helped found in 1882, but also in respected literary publications. Myers, aided by his socially ambitious wife, became the nexus for the fascination with psychical phenomena in the later Victorian period. He was well connected not only with the literati, but also with the philosophers, scientists, and mental scientists intrigued by this pursuit. Although Myers died of a respiratory ailment at a relatively early age, his magnum opus, Human Personality and its Survival of Bodily Death, published posthumously in 1903, collected hundreds of cases demonstrating extensions of personality into the realm of spirit, thus supporting his survival of personality thesis. Partly because of its controversial nature, this work was hugely influential to the point where one historian, John Cerullo, has referred to the period from 1903 to the 1920s as “the Age of Myers” in psychical research (103). Myers’s work acted as a bridge to the next generation of writers, the Edwardians and emerging modernists, and interest in it surged during and after the war as society attempted to cope with the mass trauma of war loss. Following Myers’s lead to one degree or another, writers such as Barrie, Doyle, Kipling, Sinclair, Woolf, Blackwood, and Huxley in this study, and many more besides, considered various extensions of consciousness within a construct of realism, as no longer belonging to the realm of gothic fantasy, and articulated the real possibility of telepathic or spirit communication between the living and between the living and the dead. Interestingly, Myers’s voice persisted beyond death as well, since it was purportedly channeled by an astonishing array of mediums; Myers thus had a further impact on mystical responses to loss of writers such as Sir Oliver Lodge, as detailed in Chapter 3.

In his autobiographical “Fragments of Inner Life,” Myers invites scrutiny, suggesting that readers “will prefer that [his] idiosyncrasy should not be concealed” (2). However, just before this he states:

I hold that all things thought and felt, as well as all things done, are somehow photographed imperishably upon the universe, and that my whole past will probably lie open to those with whom I have to do. Repugnant though this thought is to me, I am bound to face it. I realize that a too great discrepancy between my account of myself and the actual facts would, when detected, provoke disgust and contempt.

This statement implies an anxiety about exposure, a repugnance to it, but also a fear of discrepancy, or hypocrisy. What underlies this anxiety? Did Myers have secrets? What is the nature of his self-proclaimed idiosyncrasy? A careful examination of biographical details and the patterns that emerge, through the lens of object relations and attachment theory, can reveal new insights. In the first full-length biography of Myers, Trevor Hamilton counters an earlier biographer Fraser Nichols’s speculation that the seeds of Myers’s future troubles at Cambridge “were unwittingly planted by the love of a too-doting mother for her brilliant child” (12). Hamilton asserts:

in the light of other comments on the character of Mrs Myers, this is probably a superficial Freudian speculation. Myers grew up in a very supportive environment, had considerable natural gifts, a strong physique, and optimistic temperament, and huge energy. (12)

Myers’s environment may have been supportive up to a point, but it also was exceptional, even for the Victorian period. Myers’s father, also Frederic, born in 1811, excelled academically. He became a scholar at Clare College, Cambridge, where he received scholarships and “the Hulsean essay prize in 1830,” later becoming a fellow there (Hamilton 10). Myers took religious orders, and in 1838 became the perpetual curate of St John’s, Keswick. He married at 28, but his wife Fanny died the next year. He then married Freddie’s mother Susan two years later, and so loss and grief would have been embedded in the relationship from its beginning. Whereas he was tolerant, liberal in his religious views, and committed to educating his parishioners, his wife was much more of an evangelical. Both were ambitious, particularly in regards to Freddie. At a very early age Frederic senior taught Freddie the classics, inspiring him with a love of Virgil (10).

Susan concerned herself with Freddie’s religious education, emphasizing a literalist understanding of the Bible as well as self-improvement in preparation for the afterlife (Hamilton 12). This education she began when Freddie was just two years and nine months old, and she had him reading the Bible at just over four (Gauld 38). In the journal she kept from the time Freddie was one year and six days old until two months after her husband died when Freddie was eight, she recorded his responses to her teaching, such as his shock and grief “when good men do anything wrong,” or his “burst of tears” when she told him that the dead mole had no soul and so would not go to heaven (Gauld 39). She soon realized that he possessed a sensitive nature: “and along with this delight is a proportionate pain when he is disappointed in anything he has set his heart upon – or when his will is crossed, or his fancy, in anything” (Gauld 41). Gauld comments that “the preoccupation with death and the afterworld which Freddie had, as a result of his mother’s teachings, by then acquired would now strike the most religious people as altogether morbid, and at times it undoubtedly caused him great unhappiness” (Gauld 42). Her control and cosseting also provoked rebellion in him, and she noted: “he is not grateful or humble as I sh. [sic] like to see him” (Gauld 40). Gauld comments that “he remained careless of parental instructions, and was arrogant and overbearing with other children” (41). Trevor Hamilton cites a family friend who claimed that Mrs Myers “was a cold, hard, woman,” and that “Frederick [sic] Myers and his brothers were brought up very carefully if anything too carefully. They were almost prigishly [sic] brought up” (11). Myers himself referred to her character as of “‘the old school’; – a character of strong but controlled affections, of clear intelligence, unflinching uprightness, profound religious conviction” (“Fragments” 7). Another factor that may have provoked testing behavior is that Frederic had two brothers who came close on his heels, Ernest, when Freddie was one year and eight months old, and Arthur, when Freddie was just over two. The demands on Susan’s time would have increased enormously when her husband suddenly fell ill in the spring of 1851, and then permanently after he died in July 1851. Married just nine years, Susan must have felt abandoned, and she wrote in her diary of her “overwhelming grief,” “deep sorrow,” and great sadness (Myers 8). Part of her response was her dogged ambition to have his biography published, at which she failed, and to have published his unpublished writing, Catholic Thoughts (1873) and Lectures on Great Men (1856) at which she succeeded. His death also necessitated a move away from the beloved Lake District, first to a small house in Blackheath, and then, in 1856, to Cheltenham, where her sons could attend Cheltenham College as day boys, since, as Myers put it, “she wished to keep her sons with her” (7–8). Most importantly, again in Myers’s own words, she “made our welfare the absorbing interest of her life” (7). Myers’s sense of loss is implied in his retrospective, romantic description of the Keswick Parsonage garden where he claimed “my conscious life began”: “The memories of those years swim and sparkle in a haze of light and dew. The thought of Paradise is interwoven for me with that garden’s glory” (“Fragments” 7).

The consequences of Myers’s enmeshed relationship with his mother begin to be seen in his precocity and, in Hamilton’s words, “considerable, possibly even overweening, sense of his own worth and status” (16). While Myers’s “awe-struck joy” and “reverent emotion” at first learning and hearing Virgil’s poetry is associated with his father, the contents of his own earliest poems would seem to draw on preoccupations and feelings associated with both parents. In 1857, at age fourteen while at Cheltenham, he penned two poems about Belisarius, the Byzantine general unjustly imprisoned and betrayed by his adulterous wife. At first glance these seem unusual subject matter for a youth, but Myers’s father had written a volume on Great Men, and Frederic senior may have been presented as one by Susan. Both poems suggest that fame will outlast shame and ensure survival. One ends: “Not in vain to mourn and struggle, not in vain in shame to die / For my fame shall live beyond me, and the recompense is nigh” (60). Both poems also blame women for wrongs done: “It was a woman drove me into penury and night” (53). His other early poems focus on death and subsequent glory, such as his memorial for Robbie Burns (penned at age fifteen), “the Death of Socrates” (age sixteen), and “The Prince of Wales at the Tomb of Washington.” The last-mentioned features Washington’s communication from beyond the grave that he does not want pardon for revolting from his father’s rod, and he compares this to a family dynamic: “Neither can one consent for ever bind / Parent and offspring, but they shall at length / A closer union in disunion find, / In separation strength” (87). It is tempting to speculate that Myers might here be trying to justify or rationalize the loss of his father. Interestingly, in the poem the Prince does not respond to the voice of Washington, but “In solemn silence turned him from the spot” (90).

“The Prince of Wales” was the first poem to gain Myers notoriety when he went up to Cambridge at the early age of seventeen. Myers won the Chancellor’s medal for it in 1861 and he recited it at the Cambridge Senate house in an “uncompromising singsong” which was “received with an ominous sound of decided disapproval, compounded of laughs, groans, catcalls, and hisses,” according to a contemporary, E. M. Oakley (83–84). However, at the end of the recital he received “a regular ovation” (84). Oakley claimed that Myers “was popularly regarded in the University as a rara avis in terris, certainly eccentric, probably negligible” (83). However, his self-absorption and arrogance would lead to much greater notoriety when he was accused of plagiarizing a number of lines from an Oxford Prize Poem collection (Beer 120) in his poem which won the Camden medal for classical verse (the second time he had won this prize). Myers was excelling at Cambridge as an intellect, an athlete, and in religion, so that he came to be known as “the superb,” as he noted in his daily diary (as quoted in Hamilton 21). Evidently this went to his head, as he recollected: “Having won a Latin prize poem, I was fond of alluding to myself as a kind of Virgil among my young companions. Writing again a similar poem, I saw in my bookshelves a collection of Oxford prize poems which I picked up somewhere in order to gloat over their inferiority to my own” (as quoted in Beer 122–23). He deliberately “forced” into his poem the best lines (which he referred to as “collecting gold from Ennius’ dung heap”), and then was surprised when he was forced to resign the prize and a vote was taken on whether he would be prevented from taking his degree (Beer 122). In an explanatory letter to his uncle, Myers admitted to being “foolish, reckless, & headstrong” and of “acting on crude and sometimes presumptuous opinions without considering or regarding what others will think” (as quoted in Beer 125). He also acknowledged the momentous consequences: “my name has been held up to scorn and reproach in a great number of newspapers[,] for example Athenaeum, (as I am told), Guardian … many of my acquaintance have had their opinion of me greatly shaken & my mother has been and is seriously distressed” (as quoted in Beer 126). Nor was this an isolated incident, as Myers himself recollected: “many another act of swaggering folly mars for me the recollection of years which might have brought pure advancing congenial toil” (as quoted in Beer 123). Myers was definitely manifesting a resistant dimension in his personality. Hamilton documents that Myers cultivated an anti-intellectual front and that he went through a temporary homosexual phase. He stresses that “Myers had a desire to posture and shock as a young man (and occasionally throughout his life)” (24). By the time Myers graduated from Cambridge at twenty-two with two first-class degrees and a reputation as an intellect and poet, “he was without intellectual and emotional security” (Hamilton 33).

His arrogance and isolation mark a typical avoidant response to unmanageable and misunderstood feeling, and this pattern strikingly emerges in two voyages he made, to Greece and America. During the years from sixteen to twenty-three he seems to have projected much of his emotional turmoil into his passion for Hellenism. For him “the classics were but intensifications of my own being. They drew from me and fostered evil as well as good; they might...