![]()

1

DOMESTIC ARCHAEOLOGY AND THE ROMANO-EGYPTIAN HOUSE

An Integrated Research Agenda

Anna Lucille Boozer

Introduction

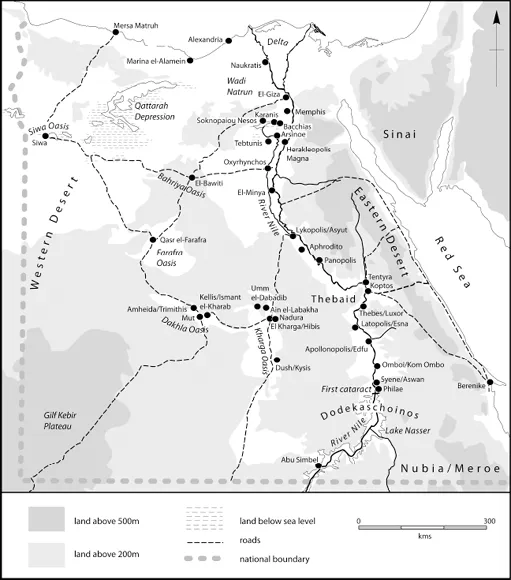

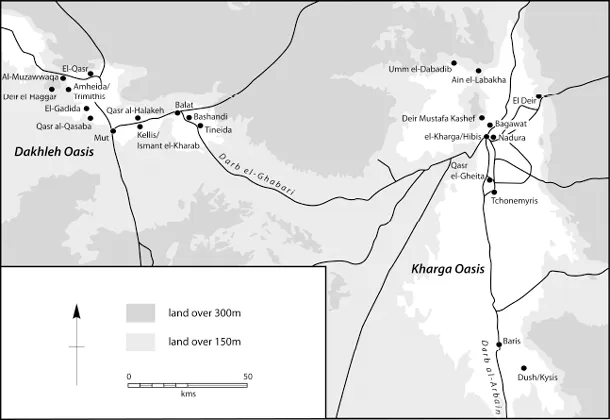

This archaeological report provides a comprehensive study of the excavations carried out at Amheida House B2 in Egypt’s Dakhla Oasis, between 2005 and 2007, followed by three study seasons between 2008 and 2010 (Figure 1.1, Figure 1.2).1 This report presents and discusses the architecture, artifacts, and ecofacts recovered from B2 in a holistic manner, which has never before been attempted in a full report on the excavation of a Romano-Egyptian house. The primary aim of this volume is to combine an architectural and material-based study with an explicitly contextual and theoretical analysis. In so doing, I hope to develop a methodology and present a case study of how the rich material remains of Romano-Egyptian houses may be used to investigate the relationship between domestic remains and social identity.

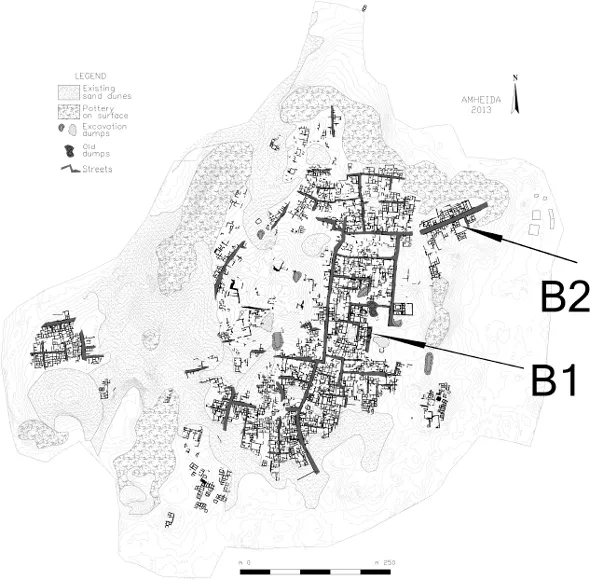

Amheida is located in the northwestern part of the Dakhla Oasis, deep within Egypt’s Western Desert. Amheida has a long occupational history, and it reached its greatest size under Roman rule (approximately first through fourth centuries CE) (Figure 1.3). The occupants left behind a wealth of documentary, pictorial, architectural, and material data, and the favorable desert conditions have preserved these remains to a high degree.

Amheida, known as Trimithis during the Roman Period, contains a diverse range of structure types within different sectors of the Roman city. The site is dominated by a large hill surmounted by a temple that was built and rebuilt over many centuries. From the surface, as well as limited excavations, it appears that elite houses lie to the south and east of the temple mound. A necropolis, with at least two pyramid tombs, extends to the southeast and south of the city. House B2 is located in the northeast sector of the city, which is composed of domestic and industrial structures. Extensive agricultural fields, predynastic lithic scatters, and Old Kingdom ceramics surround the built areas of the city. These remains of earlier periods attest to long-standing activity at Amheida before the Roman occupation of Egypt. Currently, it is neither clear what this pre-Roman settlement looked like nor how it developed over time.

Research Framework

The present study contributes to the growing corpus of data on Romano-Egyptian daily life. In particular, this volume contributes a holistic analysis of a single house (B2) in order to reveal the material components of Romano-Egyptian daily life for a single household. Romano-Egyptian domestic archaeology is still in the early stages of development, despite a long history of domestic excavation in Egypt.

Figure 1.1: Map of Egypt (M. Matthews).

Most prior research on Romano-Egyptian domestic contexts has taken place in Egypt’s Fayum (Figure 1.1). This region became a nexus for domestic studies due to the papyrological rescue missions led by Grenfell and Hunt in the early 1900s. These missions exposed numerous, well-preserved houses in the area.2 Because the primary objective of these missions was to salvage papyri, the resultant publications lack contextual and architectural data. In addition to Grenfell and Hunt’s rescue missions, other excavations took place in the Fayum, although the robustness of the data concerning them varies considerably.

Figure 1.2: Map of the Great Oasis (M. Matthews).

The University of Michigan excavated two of the most famous Fayum sites in the early twentieth century: Karanis (Kom Aushim) (1924–1934) and Soknopaiou Nesos (Dime) (1931–1932). The material recovered from these sites is invaluable for the present study since both sites produced a wealth of material data on domestic architecture and artifacts. Karanis has become the type-site of Romano-Egyptian domestic architecture, due to its good state of preservation and the care with which it was excavated compared to previous work on Romano-Egyptian houses. Since the 1930s, Karanis has appeared in numerous publications as a representative Romano-Egyptian settlement.

There are two major caveats that must be kept in mind when employing Karanis houses for comparanda.3 First, the Karanis houses have not been fully published. General reports on the stratigraphy, topography, and architecture were published in the 1930s, but these lacked full analyses of each structure and did not attempt to interpret the findings.4 A subsequent report attempted to fill in the gaps left by these prior publications, but it did not provide contextual explorations of the material, and the accompanying maps and illustrations are difficult to connect to particular structures and moments in time.5 Over the years, specialist publications on particular categories of material and of exhibitions have appeared.6 Unfortunately, we still do not have a full publication that provides the architectural layout of most of the Karanis houses. Moreover, only the largest and best-preserved houses were singled out for publication, making it difficult to discern the range of house types available at Karanis.7 This selectivity obscures the most common houses occupied by typical households at Karanis.

Figure 1.3: Amheida site map.

Second, the publications that do exist for Karanis houses analyzed material categories rather than contexts (e.g. individual houses). Nearly twenty years ago, Peter van Minnen, a papyrologist, urged archaeologists to explore Karanis domestic material by context rather than by material category.8 Unfortunately, this type of analysis has not been accomplished for more than a tiny portion of this site yet. To date, it is impossible to connect artifacts to the houses from which they came, except by consultation of the excavation records held in the Kelsey Museum. It is not possible to determine which types of objects, texts, and architectural features co-occurred with one another and what the distribution of house types, objects, and texts looked like across the site.

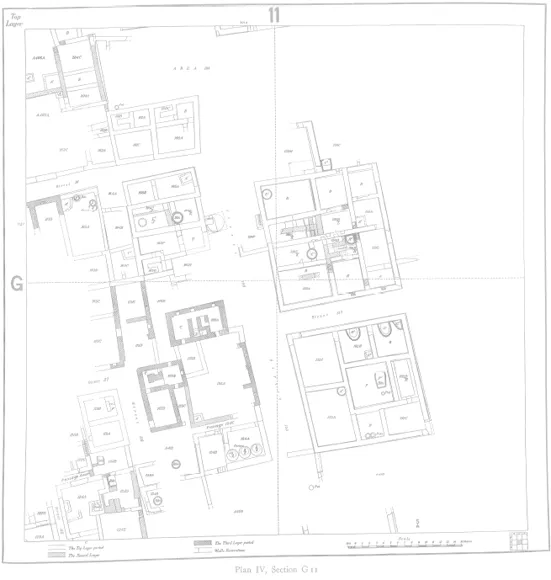

Figure 1.4: Karanis, plan IV, section G 11 in Boak, A. E. R. and E. E. Peterson, (1931). Karanis: Topographical and Architectural Report of the Excavations during the Seasons 1924-28. Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan.

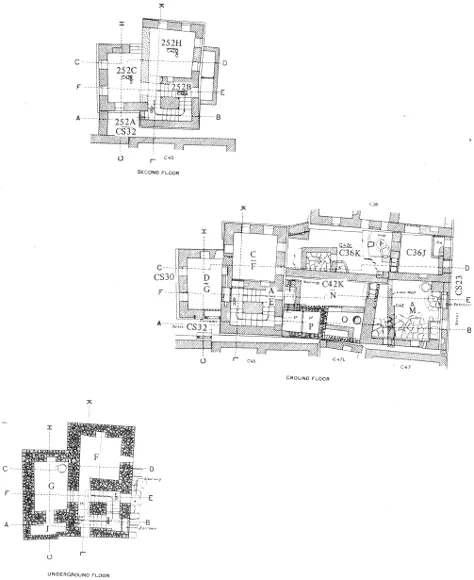

With these caveats in mind, it is possible to make some general statements about the houses excavated at Karanis. Generally, buildings at Karanis aligned into blocks of habitation (Figure 1.4).9 Although hundreds of buildings were excavated, only a few were described and drawn. The following description is reliant upon this published data, which may be revised with additional exploration of the site. These published houses were predominantly made of mud brick with only small amounts of wood used.10 Flat roofs were common, except in cellars, which were vaulted. Most houses were elongated and had multiple stories, with cooking taking place in courtyards that were either private or shared (Figure 1.5). The walls were often plastered and covered with a thin lime wash. A black wash was most common with white accents painted horizontally across the mud brick courses. Decorations were minimal and were usually found in niches, often representing religious scenes, and typically painted in maroon and black.11

Figure 1.5: Karanis, Plan 25, Floor plan of House C42 in Husselman, E. M. (1979). Karanis Excavations of the University of Michigan in Egypt, 1928-1935: Topography and Architecture: A Summary of the Reports of the Director, Enoch E. Peterson. Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan.

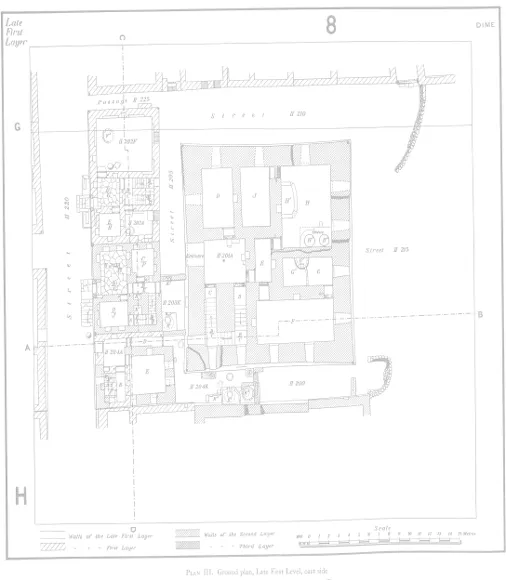

The University of Michigan also excavated houses at Soknopaiou Nesos, but the results of this mission were not fully published.12 Only the coins, papyri, and specific architectural elements received attention in the single published excavation report.13 The houses appear to have been built contiguously, and each had a courtyard to support domestic cooking needs (Figure 1.6). These structures were built directly onto bedrock. The largest house excavated had an internal courtyard (aithrion). All of the structures had a central-pillared stairway leading to upper floor(s) and often also to cellars. Poor quality wall paintings were found in some of the structures.14

Figure 1.6: Soknopaiou Nesos, plan III, ground plan, late first level, east side in Boak A. E. R. et al (1935). Soknopaiou Nesos: The University of Michigan Excavations at Dimê in 1931-32. Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan.

Other sites from Egypt’s Fayum region are even less well documented. Hawara, located at the entrance to the Fayum, is a particularly important site for Roman Egypt, although it perhaps is best-known for the pyramid of Amenemhat III (12th Dynasty). Uytterhoeven’s recent volume provides an excellent compendium of Hawara data.15 Sadly, little can be made of the ruinous Romano-Egyptian domestic remains, except that they seem to have a square or rectangular footprint averaging less than 100 m2 in area and with an adjoining exterior courtyard. These hous...