![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Textiles

EVA ANDERSSON STRAND AND ULLA MANNERING

INTRODUCTION

In its widest definition, the term textile includes more than a woven fabric, it can denote any fibrous construction, including nets, braided, and felted structures. A textile is the result of complex interactions between resources, technology, and society. The production process of a textile, from fiber to finished product, consists of several different stages. It is important to note that even when different types of textiles were produced in different periods and regions, the textile chaîne opératoire involved the same stages of production, e.g. fiber procurement, fiber preparation, spinning, weaving, and finishing, and each stage involved several sub-processes. Thus, the production of a textile is the result of, on the one hand, resources, technology, and society and, on the other, the need, wishes and choices of a population, which in turn influence the exploitation of resources. Moreover, the availability of resources condition the choices of individuals and society.1

Textiles and Preservation

In Antiquity, textiles were made from natural fibers of either plant or animal origin. Like any perishable organic material, these fibers were subject to rapid decomposition in archaeological contexts and their preservation required special conditions to avoid their destruction by micro-organisms. Environmental conditions that affect the survival of plant and animal fiber materials in positive ways are acidic conditions, favoring the preservation of proteinaceous fibers; a basic environment does the same for fibers of vegetal origin. As most degradation requires the presence of air, many archaeological textiles are found in contexts where anaerobic and/or waterlogged conditions occur. Other conditions—like extreme dryness or permanent frost, or the presence of salt, or exposure to a fire that leads to the creation of carbonized samples, or through mineralization when coming into contact with metal salts—have also preserved many textiles. In Europe, most textile remains have been found in connection with burials, such as costumes, wrappings of human remains and/or grave goods, furnishing, and other utility textiles. As the organic materials in inhumation graves are exposed to heavy and fast degradation, textiles recovered from these contexts are often highly fragmented. In northern Europe, bogs and wetland deposits have preserved many complete wool textiles and other objects made of skin and fur.2 Other important contexts where textiles or associated goods may occur are ritual offerings, settlements, refuse heaps, earth fillings and, of course, in written sources and iconography. Depending on the context, geography, and chronology, textiles have survived in differing quantities and qualities from north to south, east to west.3 In southern Europe, preservation conditions are different, finds of textiles are less well-preserved and fewer finds are known.4 By contrast, the dry conditions of Egypt have allowed a vast quantity of textiles to survive, both in the form of whole garments but, more often, in fragments.

While textile designs vary greatly, textile technology and textile tools changed less in the period under examination. In general, people were using the same raw materials, fiber processing methods, tools and textile techniques all over Europe for most of the millennium between 500 BC–AD 500, but with varying intensity and purpose.

FIBERS FOR PRODUCING TEXTILES

Plant Fibers and Their Processing

Flax deriving from the annual plant of the Linacea species, notably Linum usitatissimum, hemp (Cannabis sativa), and nettle (Urtica dioica) are plants that were used to produce textile fibers in ancient societies across Europe, North Africa and the Near East.5

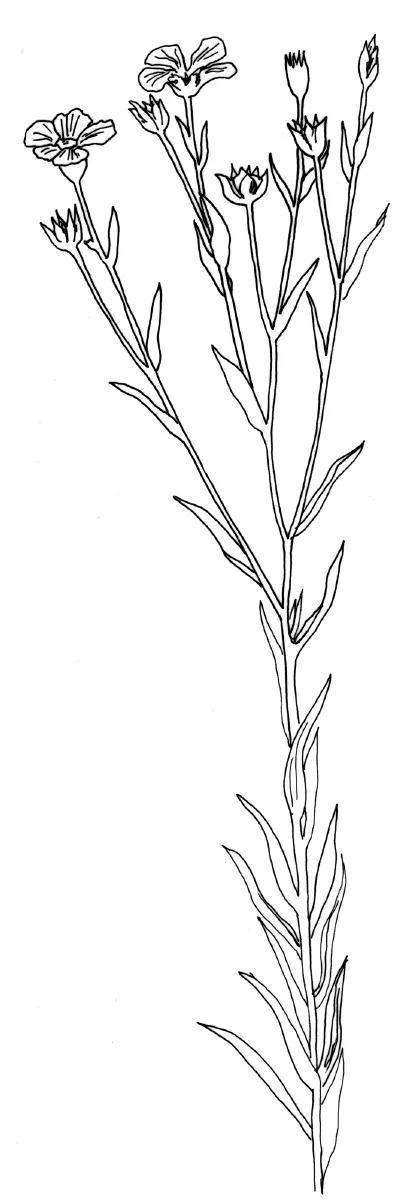

Flax (Figure 1.1) as a cultivated plant has always been considered to be one of the most important fiber plants used in ancient textile production.6 By comparing the size of preserved flax seeds from Germany and Switzerland, scholars have proposed that by the late Neolithic period (from c. 3400 BC), several different flax varieties already existed. This is supported by DNA analysis.7 Today the best quality flax fibers have a diameter of approximately 20 microns (0.002 centimeters) and are strong and soft with a fiber length of 45–100 centimeters. It has been suggested that prehistoric flax was shorter with a fiber length of 21–30 centimeters.8 Flax fibers have a silky luster and vary in color from a creamy white to a light tan. Linen textiles are cool to wear, since flax fibers conduct heat extremely well. Moreover, linen textiles have the propensity to absorb moisture very easily. At the same time, moisture evaporates quickly from them. During use, linen textiles can become almost as soft and lustrous as silk, but, in general, flax fibers lack elasticity.9

FIGURE 1.1: Flax. Courtesy of Margarita Gleba.

The best conditions for flax cultivation are fertile, well-drained loams. Depending on the region and climate, flax is sown at different times during the year. Since the roots grow near the surface and are weak, the soil has to be prepared carefully. Flax reduces the nutrients in the soil and a crop rotation with long gaps between sowing is required. The yield will otherwise be reduced and the flax will become more susceptible to disease, such as fungi attacks. During cultivation, flax needs regular access to water. It is likely that in ancient societies cultivation was well planned, especially where flax was produced on a large scale.10

When the flax is ripe it is pulled up by the roots and the seeds are stripped. The flax then has to be retted. The stems are either placed in water or spread on the ground. The moisture assists in the process of dissolving the pectin between the fibers, the bark and the stem. When flax is retted in water, it becomes extremely smelly, due to the bacterial activity. Retting pits were, therefore, usually placed outside settlement areas. The next step is breaking. In this process, a wooden club or another specialized tool, known as a break, is used to break up the dried stems and their bark in order to separate the fibers from the wooden parts (Figure 1.2). Then the flax has to be scutched, a process that scrapes away the last remains of stem and bark, which can be done with a broad wooden blade (Figure 1.3). Finally, the fibers are hackled or combed in order to separate them further and make them parallel; the fibers can also be brushed (Figure 1.4).11

FIGURE 1.2: Wooden club used to break the flax stems. © Annika Jeppsson and CTR.

FIGURE 1.3: Wooden blade used to scutch flax. © Annika Jeppsson and CTR.

FIGURE 1.4: Brush used for brushing linen fibers. © Annika Jeppsson and CTR.

Both hemp and nettle (Figure 1.5) fibers are prepared in a similar way to flax. Hemp was not used in Europe until the Iron Age.12 The hemp plant is taller than flax but the fibers are generally coarser. Most likely, hemp was preferred for the production of sails, ropes, and nets.

Archaeological finds of textiles made of nettle fibers are extremely rare, but some finds indicate that nettle was used as a textile fiber in northern Europe as well as in the Mediterranean region. Nettle fibers are, in general, shorter and thinner than flax and hemp fibers, but are well suited for producing textiles for clothing, as well as rope and other textile products. Since it is difficult to distinguish between hemp, flax, and nettle fibers, and this analysis requires specialist knowledge and equipment, archaeological plant fiber textiles have often been recorded as flax, although hemp and nettle fibers cannot be excluded. A renewed focus on species identification will hopefully provide new results on the use of various plant fibers in a European context in the future.13

Cotton is mentioned in Roman written sources, but evidence for its cultivation and use in Antiquity is scarce. It has ...