![]()

Chapter 1

Evidence-based practice

Doing the right thing for patients

Tracey Bucknall and Jo Rycroft-Malone

Introduction

Profound changes in health care have occurred as a result of advances in technology and scientific knowledge. Although these developments have improved our ability to achieve better patient outcomes, the health system has struggled to incorporate new knowledge into practice. This partly occurs because of the huge volume of new knowledge available that the average clinician is unable to keep abreast of the research evidence being published on a daily basis. A commonly held belief is that knowledge of the correct treatment options by clinicians will lead more informed decision making and therefore the correct treatment for an individual. Yet the literature is full of examples of patients receiving treatments and interventions that are known to be less effective or even harmful to patients. Although clinicians genuinely wish to do the right thing for patients, Reilly (2004) suggests that good science is just one of several components to influence health professionals. Faced with political, economic, and sociocultural considerations, in addition to scientific knowledge and patients’ preferences, decision making becomes a question of what care is appropriate for which person under what circumstances. Not surprisingly, to supplement to clinical expertise, critical appraisal has become an important prerequisite for all clinicians (nurses, physicians, and allied health) to evaluate and integrate the evidence into practice.

Although there is the potential to offer the best health care to date, many problems exist that prevent the health care system from delivering up to its potential. Globally, we have seen continuous escalation of health care costs, changes in professional and nonprofessional roles and accountability related to widespread workforce shortages, and limitations placed on the accessibility and availability of resources. A further development has been the increased access to information via multimedia, which has promoted greater involvement of consumers in their treatment and management. This combination has lead to a focus on improving the quality of health care universally and the evolution of evidence-based practice (EBP).

What is evidence-based practice?

Early descriptions simply defined EBP as the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values to facilitate clinical decision making (Sackett et al., 2000: 1). The nursing society, Sigma Theta Tau International 2005–2007 Research & Scholarship Advisory Committee (2008) further delineated evidence-based nursing as “an integration of the best evidence available, nursing expertise, and the values and preferences of the individuals, families, and communities who are served” (p.69). However, an early focus on using the best evidence to solve patient health problems oversimplified the complexity of clinical judgment and failed to acknowledge the contextual influences such as the patient’s status or the organizational resources available that change constantly and are different in every situation.

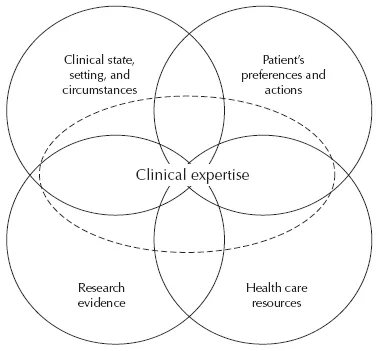

Haynes et al. (2002) expanded the definition and developed a prescriptive model for evidence-based clinical decisions. Their model focused on the individual and health care provider and incorporated the following: the patient’s clinical state, the setting and circumstances; patient preferences and actions; research evidence; and clinical expertise. Di Censo et al. (2005) expanded the model further to contain four central components: the patient’s clinical state, the setting and circumstances; patient preferences and actions; research evidence; and a new component health care resources, with all components overlaid by clinical expertise (Fig. 1.1). This conceptualization has since been incorporated into a new international position statement about EBP (STTI, 2008). This statement broadens out the concept of evidence further to include other sources of robust information such as audit data. It also includes key concepts of knowledge creation and distillation, diffusion and dissemination, and adoption, implementation, and institutionalization.

These changes to definitions and adaptations to models highlight the evolutionary process of EBP, from a description of clinical decision making to a guide that informs decisions. While there is an emphasis on a combination of multiple sources of information to inform clinicians’ decision making in practice, it remains unknown how components are weighted and trade-offs made for specific decisions.

The evolution of evidence-based practice

A British epidemiologist, Archie Cochrane, was an early activist for EBP. In his seminal work, Cochrane (1972) challenged the use of limited public funding for health care that was not based on empirical research evidence. He called for systematic reviews of research so that clinical decisions were based on the strongest available evidence. Cochrane recommended that evidence be based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) because they were more reliable than other forms of evidence. Research reviews should be systematically and rigorously prepared and updated regularly to include new evidence. These principles resonated with both the public and health care providers.

In 1987, Cochrane noted that clinical trials on the effectiveness of corticosteroid treatments in premature labor in high-risk pregnancies were supportive of treatment but had never been comprehensively analyzed. He referred to a systematic review that indicated corticosteroid therapy could reduce low-birth-weight premature infant mortality rates by 20% (Cochrane Collaboration, 2009). In recognition of his work and leadership, the first Cochrane Centre was opened 4 years after his death; the Cochrane Collaboration was founded a year later in 1993. The aim of the collaboration is to ensure that current research evidence in health care is systematically reviewed and disseminated internationally. Beginning in medicine, the collaboration now has many health professions represented on review groups including consumers.

As Kitson (2004) noted, the rise of evidence-based medicine (EBM) was in itself, a study of innovation diffusion, “offering a strong ideology, influential leaders, policy support and investment with requisite infrastructures and product” (p. 6). Early work by Sackett and team at McMaster University in Canada and Chalmers and team at Oxford in the UK propelled EBM forward, gaining international momentum. Since 1995, the Cochrane Library has published over 5000 systematic reviews, and has over 11,500 people working across 90 different countries (Cochrane Collaboration, 2009).

The application of EBM core principles spread beyond medicine and resulted in a broader concept of EBP. In nursing, research utilization (RU) was the term most commonly used from the early 1970s until the 1990s when EBP came into vogue. Estabrooks (1998) defined RU as “the use of research findings in any and all aspects of one’s work as a registered nurse” (p. 19). More recently, Di Censo et al. (2005) have argued that EBP is a more comprehensive term than RU. It includes identification of the specific problem, critical thinking to locate the sources, and determine the validity of evidence, weighting up different forms of evidence including the patients preferences, identification of the options for management, planning a strategy to implement the evidence, and evaluating the effectiveness of the plan afterwards (Di Censo et al., 2005).

The emergence of EBP has been amazingly effective in a short time because of the simple message that clinicians find hard to disagree with, that is, where possible, practice should be based on up to date, valid, and reliable research evidence (Trinder and Reynolds, 2000). In Box 1.1, four consistent reasons for the strong emergence of EBP across the health disciplines are summarized by Trinder and Reynolds (2000).

Box 1.1 The emergence of evidence-based practice (Trinder and Reynolds, 2000)

| Research–practice gap | Slow and limited use of research evidence. Dependence on training knowledge, clinical experience, expert opinion, bias and practice fads. |

| Poor quality of much research | Methodologically weak, not based on RCTs, or is inapplicable in clinical settings. |

| Information overload | Too much research, unable to distinguish between valid and reliable research and invalid and unreliable research. |

| Practice not evidence-based | Clinicians continue to use harmful and ineffective interventions. Slow or limited uptake of proven effective interventions being available. |

It is worth noting, however, that while generally accepted as an idea “whose time has come,” EBP is not without its critics. It is often challenged on the basis that it erodes professional status (as a way of “controlling” the professions), and as a reaction to the traditional hierarchy of evidence (see Rycroft-Malone, 2006 for a detailed discussion of these arguments).

Although significant investment has been provided to produce and synthesize the evidence, a considerably smaller investment has been made toward the implementation side of the process. As a consequence, we have variable levels of uptake across the health disciplines and minimal understanding of the effectiveness of interventions and strategies used to promote utilization of evidence.

What does implementation of evidence into practice mean?

In health care, there have been many terms used to imply the introduction of an innovation or change into practice such as quality improvement, practice development, adoption of innovation, dissemination, diffusion, or change management. The diversity in terminology has often evolved from the varying perspectives of those engaged in the activity such as clinicians, managers, policy makers, or researchers. Box 1.2 differentiates some of the definitions most frequently provided.

Box 1.2 What is meant by implementation?

Source: Definitions adapted from Davis and Taylor-Vaisey (1997).

| Diffusion | Information is distributed unaided, occurs naturally (passively) through clinicians adoption of policies, procedures, and practices. |

| Dissemination | Information is communicated (actively) to clinicians to improve their knowledge or skills; a target audience is selected for the dissemination. |

| Implementation | Actively and systematically integrating information into place; identifying barriers to change, targeting effective communication strategies to address barriers, using administrative and educational techniques to increase effectiveness. |

| Adoption | Clinicians commit to and actually change their practice. |

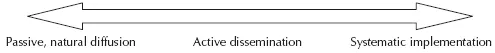

These definitions imply a continuum of implementation from the most passive form of natural diffusion after release of information toward more active dissemination where a target audience is selected and communicated the information to improve their skills and knowledge. Further along the continuum is the systematically planned, programed, and implemented strategy or intervention where barriers are identified and addressed and enablers are used to promote implementation for maximum engagement and sustainability (Fig. 1.2).

Implementation in health care has also been informed by many different research traditions. In a systematic review of the literature on diffusion, dissemination, and sustainability of innovations in health services, Greenhalgh et al. (2004) found 11 different research traditions that were relevant to understanding implementation in health care. These were: Diffusion of innovations; rural sociology; medical sociology; communication; marketing and economics; development studies; health promotion; EBM; organizational studies; narrative organizational studies; complexity and general systems theory. Box 1.3 outlines the research traditions and some key findings derived from the research.

Box 1.3 Examples of research traditions influencing diffusion, dissemination, and sustainable change

Source: Adapted from Greenhalgh et al. (2004).

|

| Diffusion of innovation | Innovation originates at a point and diffuses outward (Ryan, 1969). |

| Rural sociology | People copy and adopt new ideas from opinion leaders (Ryan and Gross, 1943). |

| Medical sociology | Innovations spread through social networks (Coleman et al., 1966). |

| Communication | Persuading consumers while informing them (MacDonald, 2002). More effective if source and receiver share values and beliefs (MacGuire, 1978). |

| Marketing and economics | Persuading consumers to purchase a product or service. Mass media creates awareness; interpersonal channels promote adoption (MacGuire, 1978). |

| Development studies | Social inequities need to be addressed if widespread diffusion is to occur across different socioeconomic groups and lead to greater equity (Bourdenave, 1976). |

| Health promotion | Creating an awareness of the problem and offering a solution through social marketing. Messengers and change agents from target group increase success (MacDonald, 2002; Rogers, 1995). |

| Evidence-based medicine | No causal link between the supply of information and its usage. Complexity of intervention and context influence implementation in real world (Greenhalgh et al., 2004). |

| Organizational studies | Innovation as knowledge is characterized by uncertainty, immeasurability, and context dependence (Greenhalgh et al., 2004). |

| Narrative organizational studies | Storytelling captures the complex interplay of actions and contexts; humanizing and sense-making, creating imaginative and memorable organizational folklore (Greenhalgh et al., 2004; Gabriel, 2000). |

| Complexity and general systems | Complex systems are adaptive, self-organizing and responsive to different environments. Innovations spread via the local self-organizing interaction of actors and units (Plsek and Greenhalgh, 2001). |

The many different research traditions have used diverse research methods that at times produce contrasting results. For researchers, it offers significant flexibility in research design and depends on the research questions being asked and tested. For clinicians and managers, research theories offer guidance for developing interventions by exposing essential elements to be considered. These elements are often grouped at individual, organizational, and environmental levels, as they require different activities and strategies to address the element. The following section offers a limited review of the different attributes that are known to influence the success of implementation and need to be considered prior to implementing evidence into practice.

Attributes influencing successful implementation

Unlike the rapid spread associated with some forms of technology, which may simply require the intuitive use of a gadget and little persuasion to purchase it, many health care changes are complex interventions requiring significant skills and knowledge to make clinical decisions prior to integration into practice. Not surprisingly then, implementation of evidence into practice is mostly a protracted process, consisting of multiple steps, with varying degrees of complexity depending on the context. Numerous challenges arise out of the process that can be categorized into following five areas (Greenhalgh et al., 2004): the evidence or information to be implemented, the individual clinicians who need to learn about the new evidence, the structure and function of health care organizations, the communication and facilitation of the evidence, and lastly, the circumstances of the patient who will be the receiver of the new evidence. These challenges need to be considered when tailoring interventions and strategies to the requirements of various stakeholders (Bucknall, 2006).

The evidence

There is much literature indi...