![]()

Module II

Governance Structures in Private Equity

![]()

Chapter 9

The Private Equity Governance Model

Harry Cendrowski

Adam A. Wadecki

Introduction

Private equity (PE) firms possess unique governance structures that permit them to be active investors in the truest sense of the term. Through large equity stakes, management interests in PE portfolio companies become aligned with those of all shareholders, and a sense of ambition is instilled in the executives managing these firms.

This chapter explores the PE governance model and the significant differences between it and the governance structures of public corporations. Implications for publicly traded PE firms are also discussed.

A New Model for Corporate Governance

In 1989, noted Harvard Business School Professor Michael C. Jensen wrote, “The publicly held corporation, the main engine of economic progress in the United States for a century, has outlived its usefulness in many sectors of the economy and is being eclipsed.” Jensen appropriately titled his article in the Harvard Business Review, “Eclipse of the Public Corporation.” Central to Jensen's article was the notion that PE firms, “organizations that are corporate in form but have no public shareholders,” were emerging in place of public corporations.1

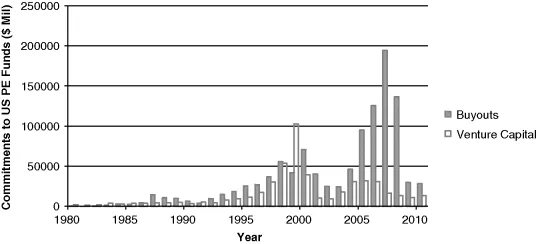

In the late 1980s, the PE market was burgeoning. With the U.S. Department of Labor's clarifications to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) in 1979 came significant inflows to alternative asset classes. As shown in Exhibit 9.1, PE fundraising levels increased from just over $2 billion in 1980 to roughly $14 billion by 1989, a compound annual growth rate of 24 percent.

Buyouts gained in popularity throughout the 1980s as interest rates, now available at half the rates of the early 1980s, decreased significantly and the number of distressed corporations grew. With some equity investors earning as much as 60 to 100 percent per year on their investments, the buyout binge was born.2 Managers overseeing portfolios at institutional investment firms began allocating large portions of their portfolios to PE in an attempt to both diversify their investments and achieve higher rates of return than what was available in public markets.

Entire industries were restructured during this time period, including the automotive supply, rubber tire, and casting industries, among others. The tire industry during this time was characterized by the chief executive officer (CEO) of Uniroyal Goodrich as a “dog-eat-dog business.”3 Those companies that survived these difficult times moved swiftly to counteract the fierce headwinds caused by intense competition; others that failed to perceive these fundamental changes in their external environment experienced significant hardships.

With the growth in PE investments came increased scrutiny from the public—especially for buyout funds—and a general distaste for the tactics employed by leveraged buyout (LBO) shops. A 1989 article in the Wall Street Journal expressed investors' growing antipathy for the structure of such transactions:

During the buyout craze of the 1980s, many saw buyout shops as a new kind of “evil empire,” mercilessly slashing costs at portfolio firms in order to increase exit multiples, and hence, a business's valuation. It was during the late 1980s that some of the buyout's largest magnates, like T. Boone Pickens and Carl Icahn, earned their reputation for purchasing distressed firms, laying off employees, cutting research and development (R&D) budgets, and subsequently selling off parts of the company to the highest bidder. Other public company figures like “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap only helped to fuel both Wall Street's and American consumers' distaste for such operational methods.

Working as a CEO at Lily Tulip Corporation, Dunlap “fired most of the senior managers, sold the corporate jet, closed the headquarters and two factories, dumped half the headquarters staff, and laid off a bunch of other workers. The stock price rose from $1.77 to $18.55 in his two-and-a-half-year tenure.” Subsequently, while at Scott Paper, Dunlap “fired 11,000 employees (including half the managers and 20 percent of the company's hourly workers), eliminated the corporation's $3-million philanthropy budget, slashed R&D spending, and closed factories. Scott's market value stood at about $3 billion when Dunlap arrived in mid-1994. In late 1995, he sold Scott to Kimberly-Clark for $9.4 billion, pocketing $100 million for himself. . .”5 However, despite a general disinclination toward such methods, defenders of the buyout boom aptly pointed out that many firms purchased by buyout funds might have gone out of business if it were not for their sometimes cutthroat practices.

Until the past decade, PE funds generally focused on targeting either growing firms or declining businesses participating in mature industries: the former was the focus of venture capitalists, while the latter was the focus of buyout funds. In recent years, however, buyout funds have moved away from purc...