![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

1.1 THE LANGUAGES OF THE BIBLE

The Christian Bible is a collection of 66 books and letters written over a considerable period of time. The Old Testament is the Jewish canon of scripture, containing the 5 books of the law (the Torah), 12 history books, 5 poetry books and 17 books of prophecy. These distinctions are somewhat arbitrary as, for example, there are historical accounts in some of the law books and the prophets. The New Testament is the Christian canon of scripture and contains four gospels, one history book, 21 letters and one book of prophecy.

The Old Testament was written mostly in Hebrew, with some parts of the book of Daniel written in Aramaic, which was a common language of the Babylonian court. The Kingdom of Israel divided into two parts in about 928 BC when Rehoboam succeeded his father Solomon as king and Jeroboam, son of Nabat, broke away forming a Northern kingdom initially known as Israel but later called after its capital city, Samaria. The Southern kingdom became known as Judah after the land allotted to the tribe of Judah on division of the Promised Land. In about 720 BC, the Assyrians invaded Samaria and it became an Assyrian province until the Babylonian invasion. The Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar conquered both Samaria and Judah, capturing and destroying Jerusalem on 16th March 597 BC. Nebuchadnezzar deported many Jews to Babylon and both Samaria and Judah became Babylonian provinces. The Persian, Cyrus the Great, conquered Babylon in October 539 BC. He employed a more devolved system of government and allowed the Jewish exiles to return to their land, both Samaria and Judah becoming Persian satrapies, and encouraged the rebuilding of Jerusalem. The Persian Empire was, in turn, overthrown by the Greeks under Alexander the Great in 331 BC. Alexander built a Greek Empire that stretched from Spain to India, and Greek became the common language of that Empire. On Alexander's death on 10th June 323 BC, there was a struggle for succession and his empire fragmented. Egypt came under control of the Ptolemies and Syria, including the Holy Land, under the Seleucids. By this time, Jews were living in many parts of what had been Alexander's empire and some were beginning to lose the ability to read Hebrew. It is said that the first translation of the Jewish Bible into Greek was requested by Ptolemy II in Egypt. Modification and refinements of the translations were made, possibly to bring them closer to the Hebrew. The Septuagint is a translation that dates from the 2nd century BC and manuscripts of the Septuagint were found in the cave at Qumran (The Dead Sea Scrolls). This version of the Jewish Bible was the one in common use by Hellenised communities and is the version used in New Testament citations of the Old Testament. However, the Septuagint contains more material than there is in the Hebrew Bible. The additional 15 books and parts of books are nowadays known as the Apocrypha. The Apocrypha is not recognised as canonical scripture by either Judaism or Protestant Christianity and, although some references to perfume from it are used here, it was not a major part of the research for this present book. In the 2nd century BC, Judas Maccabeus and his brother led a Jewish revolt against Seleucid rule and invited the Romans to set up a garrison in Jerusalem to protect them from the Seleucids. By New Testament times, the Roman Empire had replaced the Greek as the major power in Europe and the Middle East. However, Greek continued to be the common language of the Eastern part of the Roman Empire, and all educated Romans could read Greek. Therefore, although the native tongue of all but one of the writers of the New Testament would have been Aramaic, they wrote in Greek. Luke, who wrote the third gospel and the Acts of the Apostles, was the only contributor whose native language was Greek.

The implications for this present work are significant. Searches in Hebrew (Old Testament), Greek (Septuagint and New Testament) and English (various translations) identified words associated with perfume, perfumers, scents and the sense of smell but comparisons between translations are not always consistent. For example, the Hebrew word רֹקֵ֑חַ (rō·w·qê·aḥ) is found in Exodus, 30.35; 1 Samuel, 8.13; and Nehemiah, 3.8. In modern Hebrew, it means pharmacist. In Exodus and 1 Samuel, the Greek of the Septuagint gives μυρεψικος (murepsikos), which means perfumer, and in Nehemiah, the Septuagint simply gives a phonetic representation of the Hebrew word. In some English translations, we find apothecary and, in others, perfumer. A discussion of this and similar problems of translations will be found in appropriate places in this book.

1.2 PERFUME AND THE BIBLE

Perfumery is one of the oldest industries and is mentioned in the writings of all ancient civilisations; therefore, it is not surprising that we also find it mentioned in the Bible. In fact, there are references to perfume in 24 of the 39 books of the Old Testament and in 9 of the 27 books of the New Testament. Thus, 61% of the books of the Old Testament mention perfume, as do 33% of those of the New Testament. In total, 33 of the 66 books of the Christian Bible mention perfume. In other words, perfume is included in 50% of the books of the Bible.

The first reference to perfume is right at the beginning of the Bible. In Genesis, 2.12, we are told that the land of חֲוִילָ֔ה (ḥă·wî·lāh) (Havilah) is a source of aromatic resins. Havilah is probably the Horn of Africa, an area which remains, to this day, a major source of resins such as frankincense. The same sentence in Genesis also refers to gold and so this could be an example of typology since “aromatic resin” could include frankincense and myrrh, and hence the text could foreshadow all three of the gifts brought by the magi to the infant Jesus (Matthew, 2.11).

The last reference to perfume comes right at the end of the Bible in Revelation, 18.13. Here, John lists various items of trade in a city that he calls Babylon. These articles include a number of perfumes and perfume ingredients: cinnamon, spice, incense, myrrh and frankincense. The ancient Chaldean city of Babylon was indeed famous for its trade in perfume materials. However, many parts of the Bible are intended to be metaphorical rather than literal and this passage is one of those. John is unlikely to be talking about that ancient imperial capital because it was razed to the ground many hundreds of years before John had his revelation on Patmos. When John refers to Babylon, he seems to be referring to Rome. In Revelation, 17.5, he describes Babylon as a woman, and in Revelation, 17.9, he says that the woman sits on seven hills. The city of Rome is built on seven hills. In John's day, to refer to Rome directly in the terms he uses in Revelation, 17, would have been very dangerous, hence I believe that he used metaphorical language which early Christians would have understood readily. However, whether he is speaking of Babylon or Rome, his message applies equally to the materialistic world which both cities typify and in which we still live.

The densest source of references to perfume is in the Song of Songs, sometimes known as the Song of Solomon (for example, Song of Songs, 1.3; 1.13; 3.6; 4.6; 4.10; 4.13; 4.14; 5.5; 5.13). This is a book of beautiful love poetry, sometimes expressing the thoughts of the lover, sometimes those of his beloved and occasionally interjections from their friends. The title “Song of Solomon” originated from the possibility that the lover in question was Solomon, David's son and successor as king and builder of the first temple in Jerusalem. Although being essentially romantic poetry, its place in the Bible can be justified on the basis of its being a metaphor for the love between God and humans.

1.3 METAPHORICAL AND LITERAL

Biblical references to perfume are sometimes metaphorical and sometimes literal and often are both simultaneously.

In the Song of Songs, the beloved tells her lover that his perfume is pleasing and so it is no surprise that all the girls love him (Song of Songs, 1.3), and she describes him as being perfumed with myrrh and incense (Song of Songs, 3.6). Such references are clearly intended literally. Similarly, when we are told that perfume and incense bring joy to the heart (Proverbs, 27.9), it is a simple literal statement.

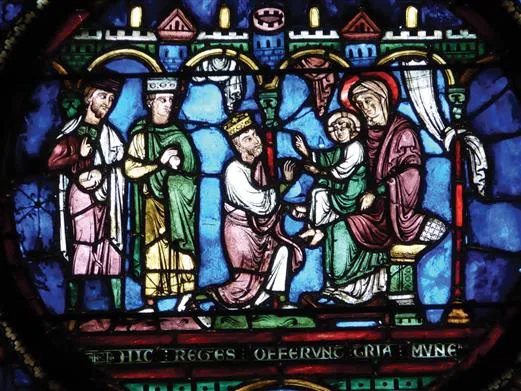

Perhaps the best known reference to perfumes is found in the account of the visit of the magi to the infant Jesus (Matthew, 2.11), as prophesied by Isaiah (Isaiah, 60.6). The magi were probably Zoroastrian astrologers, and they brought gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. Since the magi came looking for a new king, it is not surprising that they brought expensive gifts for him. Thus, this account has a literal element; but it also has a metaphorical aspect. Two of the gifts are perfume ingredients and, as noted earlier, are included in both the first and last mentions of perfume in the Bible. Frankincense is an important ingredient in incense and hence has close associations with religious ritual and the priesthood. Myrrh contains pain killing substances and was a common component of mixtures used for embalming bodies. Consequently, it is associated with suffering and death. Thus, the three gifts brought by the magi each symbolise an aspect of Jesus’ life. Gold represents his kingship, frankincense his priesthood and myrrh foreshadows his suffering in Gethsemane and death on Calvary.

The adoration of the magi and the gifts they brought to the infant Jesus have been portrayed in many ways by artists through the two millennia since their visit. Figure 1.1 shows a panel from one of the Bible Windows that can be found in the North Quire aisle of Canterbury Cathedral and it combines both the adoration of the magi and the visit of the shepherds. A different depiction in glass can be found in Troyes Cathedral, as shown in Figure 1.2. Le Mans Cathedral has a bas relief carving in wood showing the scene (Figure 1.3) and Chartres Cathedral has a scene comprising statuary in the local stone (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.1 Adoration of the magi.

Reproduced with permission from the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury.

Figure 1.2 Adoration of the magi depicted in a window of Troyes Cathedral.

Figure 1.3 Bas relief wood carving in Le Mans Cathedral showing the adoration of the magi.

Figure 1.4 Sculptures in Chartres Cathedral showing the adoration of the magi.

An example of a purely metaphorical reference to perfume can be found in the Apocrypha, where wisdom is described as being like a perfume containing cassia and spreading its fragrance like myrrh, galbanum, onycha and styrax (Ecclesiasticus, 24.13–17). In another example of metaphorical use of perfume, Saint John equates the prayers of the saints with incense in his Revelation (Revelation, 5.8).

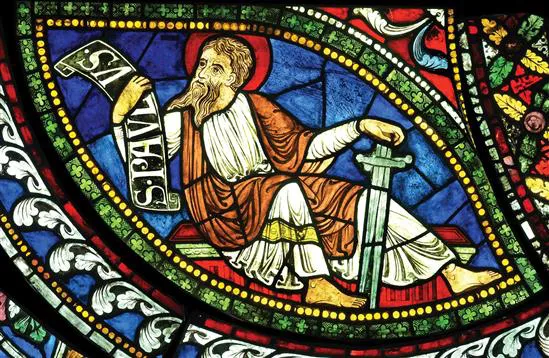

One striking example of a description of perfume that is intended to be metaphorical but has deep literal significance can be found in Saint Paul's second letter to the Christian church in the Greek city of Corinth. Paul wrote, “But thanks be to God, who always leads us in triumphal procession in Christ and through us spreads everywhere the fragrance of the knowledge of him. For we are to God the aroma of Christ among those who are being saved and those who are perishing. To the one we are the smell of death; to the other, the fragrance of life.” (2 Corinthians, 2.14–16, translation copyright © 1973 1978 1984 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™. Used by permission.) Here, Paul likens the spread of the Christian gospel through the world to the spreading of perfume through the air, and he also points out that different people respond very differently, both to smell and to the gospel. His analogy relies on two aspects of perfume and odour which he clearly understood well, though certainly not with the scientific detail that we have nowadays. This brings us on to the subject of how we perceive smell. Saint Paul is depicted in the South oculus of Canterbury Cathedral, as shown in Figure 1.5.

Figure 1.5 Saint Paul.

Reproduced with permission from the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

How the Sense of Smell Works

2.1 THE ROLE OF SMELL AND TASTE

Smell and taste are the oldest of our senses. Both are based on the ability to detect and recognise chemicals present in the environment. Even the simplest single celled organisms have receptors on the cell surface that can detect chemicals in their environment. The basic mechanism then evolved in higher organisms to give the more sophisticated senses that we know as smell and taste. As far as humans are concerned, we have only five tastes: salt, sweet, sour, bitter and umami. Umami is the taste of glutamic acid and its salts such as monosodium glutamate. Glutamic acid is one of the 20 amino acids that are essential components of the proteins in our bodies, and this taste ensures that we consume sufficient protein in our diets. Similarly, the salt taste ensures that we consume a sufficient, but not excessive, quantity of electrolytes, and the sweet taste leads us to consume carbohydrates, a key source of energy for our bodies. The sour and bitter tastes give warnings of food that contains harmful bacteria and is beginning to decompose and also warn of toxins present in some plants, such as atropine in nightshade, and thus deter us from eating them. When we drink black, unswe...