1.1. Symbols and the Group Property

A large part of mathematics involves the translation of everyday experience into symbols which are then combined and manipulated, according to determinable rules, in order to yield useful conclusions. In counting, the symbols we use stand for numbers and we make such statements as 2 + 3 = 5 without giving much thought to the meaning of either the symbols themselves or the signs + (which indicates some kind of combination) and = (which indicates some kind of equivalence). In group theory we use symbols in a much wider sense. They may, for instance, stand for geometrical operations such as rotations of a rigid body; and the notions of combination and equivalence must then be defined operationally before we can start translating our observations into symbols. We do arithmetic without much thought. only because we are so familiar with the operational definitions, which are far from trivial, which we learnt as children. But it is worth reminding ourselves how we began to use symbols.

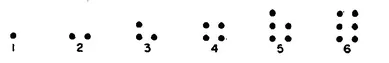

How did we learn to count? Perhaps we took sets of beads, as in Fig. 1.1, giving each set a name 1, 2, 3, . . . (the “ whole numbers ”). A set of cows, for example, can then be given the name 3, or said to contain 3 cows, if its members can be put in “ one-to-one correspondence ” with the beads of the set named 3 (a bead for each cow, no cows or beads left over). The same number is associated with different sets if, and only if, their members can be put in one-to-one correspondence : in this case the numbers of objects in the different sets are equal. If x objects in one set can be related in this way to y objects in another set we write x = y. If the numbers of fingers on my two hands are x and y, I can say x = y because I can put them into one-to-one correspondence: and I can say x = y = 5 because I can put the members of either set in one-to-one correspondence with those in the set named 5 in Fig. 1.1. This provides an operational definition of the symbol =. We observe that the sets in Fig. 1.1 have been given distinct names because none can be put in one-to-one correspondence with any other: 1 ≠ 2 ≠ 3 ≠ 4 . . . . Numbers may be combined under addition (or “ added ”), for which we usually use the symbol +, by putting together different sets to make a new set. If we put together a set of 4 objects and a set of 1 object the resultant set is said to contain (4+1) objects: but there is another name for the number of objects in this set because it can be put in one-to-one correspondence with the set of 5 objects. Hence the different collections contain equal numbers of objects and we write 4 + 1 = 5. The whole numbers are conveniently arranged in the ordered sequence (Fig. 1.1) such that 1 + 1 = 2, 2 + 1 = 3, 3 + 1 = 4, etc., so that sets associated with successive numbers are related by the addition of 1 object. Generally, we say that if the members of sets containing x and y objects, when put together to form a new set, can be put into one-to-one correspondence with those of a set of z objects, then x + y = z. The operational meaning of the law of combination (indicated by the + ) and of the equivalence ( = ) is now absolutely clear. But, of course, the terminology is quite arbitrary: instead of 2 + 3 = 5 we could just as well write

2 combined with 3 gives 5 or 2 ! 3 : 5

What matters is that we agree upon (i) what the symbols stand for, (ii) what we shall understand by saying two of them are equal, or equivalent, and (iii) what we shall understand by combining them.

FIG. 1.1. Sets of objects representing the whole numbers.

In group theory we deal with collections of symbols, A, B, . . . , R, . . . , which do not necessarily stand for numbers and which are accordingly set in distinctive type (gill sans—instead of the usual italic letters). We refer to the members of the collection as “elements” and often denote the whole collection by showing one or more typical elements in braces, {R} or {A, B, . . . , R, . . . }. The elements may, for example, represent geometrical operations such as rotations of a rigid body, and the law of combination is then non-...