Crystallography is concerned with the structure and properties of the crystalline state. Crystals have been the subject of study and speculation for hundreds of years, and everyone has some familiarity with their properties. We will concentrate on those aspects of the science of crystallography that are of interest to chemists. Our knowledge of chemistry will help us to understand the structures and properties of crystals, and we will see how the study of crystals can provide new chemical information.

1-1 Definition of a crystal

Crystals frequently have characteristic polyhedral shapes, bounded by flat faces, and much of the beauty of crystals is due to this face development. Many of the earliest contributions to crystallography were based on observations of shapes, and the study of morphology is still important for recognizing and identifying specimens. However, faces can be ground away or destroyed, and they are not essential to a modern definition of a crystal. Furthermore, crystals are often too small to be seen without a high-powered microscope, and many substances consist of thousands of tiny crystals (polycrystalline). Metals are crystalline, but the individual crystals are often very small, and faces are not apparent. The following definition provides a more precise criterion for distinguishing crystalline from noncrystalline matter.

A crystal consists of atoms arranged in a pattern that repeats periodically in three dimensions.1

The pattern referred to in this definition can consist of a single atom, a group of atoms, a molecule, or a group of molecules. The important feature of a crystal is the periodicity or regularity of the arrangement of these patterns. The atoms in benzene, for example, are arranged in patterns with six carbon atoms at the vertices of a regular hexagon and one hydrogen atom attached to each carbon atom, but in liquid benzene there is no regularity in the arrangement of these patterns.

The fact that benzene is a liquid rather than a gas at room temperature is evidence of the existence of attractive forces between the molecules. In the case of benzene these are relatively weak van der Waals’ forces, and thermal agitation keeps the molecules from associating into ordered clusters. If benzene is cooled below its freezing point of 5.5°C, the kinetic energy of the molecules is no longer sufficient to overcome the intermolecular attractions. The molecules assume fixed orientations and positions with respect to each other, and solidification occurs. As each molecule joins the growing solid particle, it is oriented so as to minimize the forces acting upon it. Each molecule entering the solid phase is influenced in almost exactly the same way as the preceding molecule, and the solid particle consists of a three-dimensional ordered array of molecules; that is, it is a crystal.2

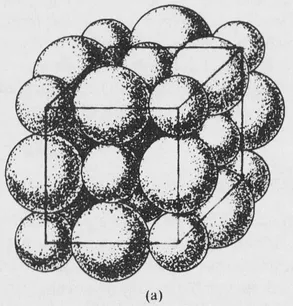

FIG. 1-1 (a) Portion of the sodium chloride structure showing the sizes of the ions, magnified about 108 times.

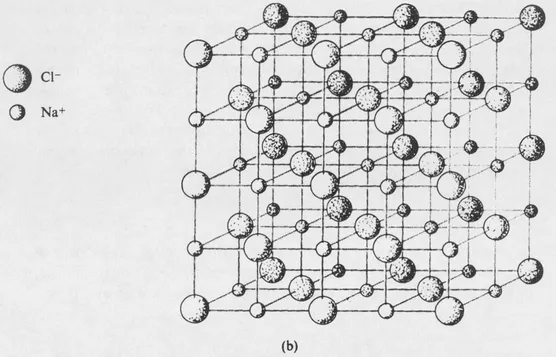

FIG. 1-1 (b) A model showing the geometrical arrangement of the sodium chloride structure.

Another example is afforded by a crystal of sodium chloride. The crystal contains many positive and negative ions held together by electrostatic attractions. The details of the arrangement depend upon the balancing of attractive and repulsive forces, which include both electrostatic and ionic size effects. The structure of sodium chloride is shown in Fig. 1-1, and further discussion will be given in Section 7-8. Each ion is surrounded by six ions of opposite charge, at the vertices of a regular octahedron, and the crystal structure represents an arrangement of these ions that leads to a potential energy minimum.

The point we want to emphasize here is that the formation of a solid particle naturally leads to crystallinity. There is a preferred orientation and position for each molecule to attach to the solid, and if the rate of deposition is slow enough to let the molecules attain this favored arrangement, the structure will fit our definition of a crystal. We have a pattern consisting of atoms or molecules. This pattern may be as simple as a single atom or it many consist of several molecules, each of which may contain many atoms. This entire pattern repeats over and over again, at regularly spaced intervals and with the same orientation, throughout the crystal.

1-2 Lattice points

Suppose we imagine a tiny creature wandering through the interior of a crystal. He stops at some point and closely examines his surroundings, and he carefully notes his position relative to the various atoms that constitute the pattern. He then walks in a straight line to an identical point in an adjacent pattern. For example, he might travel from one Na+ ion to another Na+ ion in sodium chloride or from the center of one ring to the center of another ring in benzene. When he arrives at this second point, there is absolutely nothing in his environment that will enable him to detect that he has moved at all. Furthermore, if he continues his walk without turning, he will come to another identical point when he has covered the same distance. Of course, the surroundings will look different near the surface, but in much of our discussion we will assume that the crystal contains so many repeating patterns that surface effects are quite negligible.

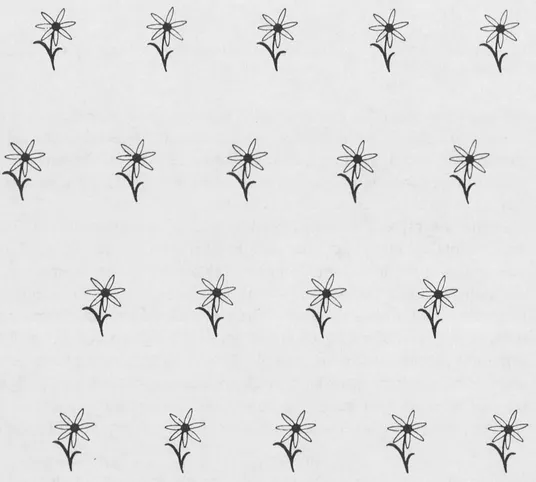

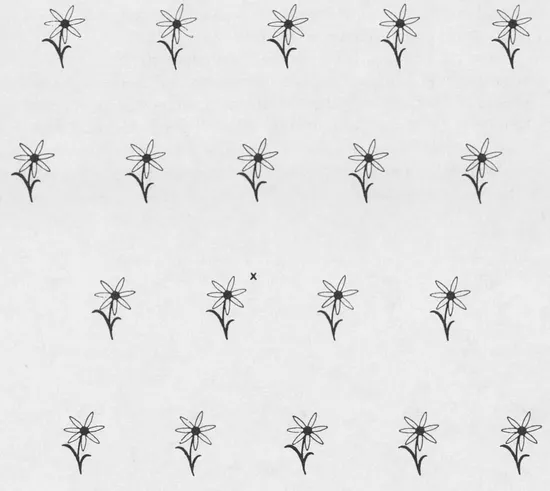

FIG. 1-2 A two-dimensional periodic structure.

A useful two-dimensional analog of a crystal is an infinite wall covered with paper. The wallpaper pattern can be of any complexity, and the entire pattern repeats periodically in two dimensions. The array is actually periodic in the direction defined by any line connecting two identical points, but all of these directions can be described by taking vector sums of two arbitrary nonparallel base vectors.

Fi...