![]()

PART ONE

The Nature of Sound

![]()

Chapter One

THE ART AND SCIENCE OF MUSIC

The word science stems from the Latin root scire, meaning “to know.” It is a branch of human endeavor in which nature is studied and analyzed in an attempt to understand its structure and behavior. Music is thought of as an art form, a refinement of the production and reception of sound.

1.1 Music of the spheres

Music and science may seem to many to be quite far apart. Yet these subjects are related in many interesting ways. The study of the relation between nature and musical harmony extends back into antiquity. During the sixth century B.C., Pythagoras and his followers1 believed both mathematics and music to be expressions of the harmony of nature (see Figure 1–1). The findings attributed to Pythagoras can be expressed as follows: Pluck a stretched string and perceive its pitch. If now only one-half the length of the string is allowed to vibrate, it will sound an octave higher. If two-thirds of the string is allowed to vibrate, it will sound a perfect fifth higher. A length of three-fourths will sound a perfect fourth higher; and so on. These relationships were perceived as harmonious, in the broadest sense.

The harmonious relationship was recognized in terms of the vibrating portions of the string, expressed as simple mathematical relationships: 2:1= octave, 3:2 = fifth, 4:3 = fourth, and so forth. These perfect musical consonances were directly related to simple relationships of whole numbers.

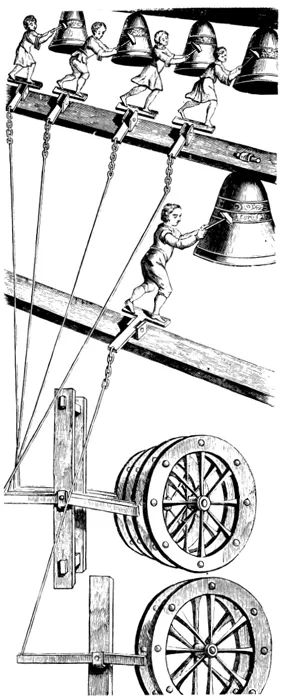

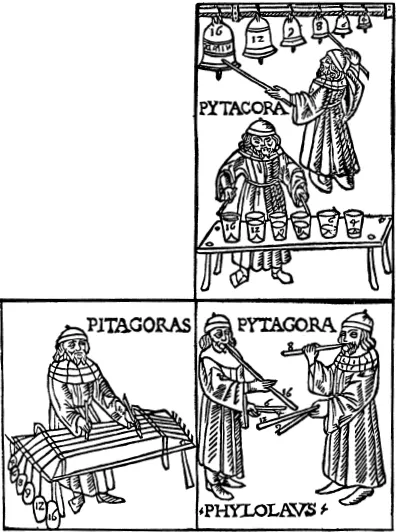

FIGURE 1–1 Demonstration of harmonic proportions from Franchino Gafurio’s “Theorica Musice” of 1492. In these diagrams Pythagoras is seen with his follower Philolaus demonstrating the tones of bells of different sizes, glasses filled to different levels, strings that are stretched by different weights, and pipes of different lengths.

The ancient Greeks were strongly oriented toward harmonies in nature, and music was simply one of these natural harmonies. The Pythagoreans carried their concept of natural musical harmony far beyond mathematics. They believed that all regularities in nature are musical. In particular, they believed that the planets produced harmonious sounds as they moved in space. This is the “music of the spheres,” a harmonious relationship of the heavenly bodies.1

Various aspects of the Pythagorean school affected the understanding of nature and music well into the Middle Ages.2 Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), a tavern keeper who became an astronomer, was the first to reduce the studies of planetary motion to three laws of motion. Nevertheless, he too was entranced by the concept of a celestial chorus, and he speculated on which planet sang soprano, which tenor, and so on.3

1.2 The science of acoustics

As science and music developed from the seventeenth century on, scientists and musicians continued to take an interest in each other’s activities. Scientists are often amateur musicians, and musicians are often amateur scientists. As time passed, breakthroughs were made in understanding sound through the studies of acoustical pioneers such as Sauveur, Mersenne, Chladni, and many others.4 As acoustics developed, its principles were applied to the development of music and musical instruments by designers such as Boehm, Sax, and others.

In recent years, the science of acoustics has developed to the point where its impact on the understanding of music is truly significant. Unfortunately, many people are suspicious of science, tending to equate it with negative aspects of technology. Others fear that an analytical approach may detract from the “mystique” of the aesthetic experience. Some simply avoid science as a result of an unfortunate experience in a science or mathematics class. It is the hope of many musicians and scientists, however, that through cooperation and mutual understanding, music can be a more effective means of enhancing the intellectual and aesthetic experience of everyone. It is in this spirit that this book is written.

1.3 Subjective and objective descriptions

Musicians and scientists have many characteristics in common. They are both creative, they relate emotionally to their activities, and they enjoy communicating their activities with others. A basic difference, however, is that the scientist attempts to describe a situation in objective terms. That is, he or she will use instruments capable of taking quantitative measurements. In so doing, the results can be expressed unambiguously, consistently, and often in numerical terms. For example, sound intensity can be expressed in picowatts per square meter or in decibels.

Among musicians it is common practice to use subjective or perceptual descriptions. For example, a tone can be described as bright, dark, hollow, nasal, harsh, pure, golden, vibrant, rich, round, tinny, raspy, woody, reedy, mellow, fuzzy, and so on. Since sensory experience is what music is all about, subjective descriptions seem appropriate. However, it is difficult to try to explain the meaning of subjective terms verbally. To convey what is meant by a “bright sound,” for example, it is customary to create several such sounds as examples. To the trained ear, this is usually adequate, although it is never totally unambiguous.

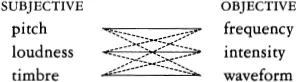

It may seem that an objective description could be found for every sensory experience. For example, one could conceivably express loudness in units of intensity, pitch as vibration frequency, and so forth. Careful study, however, almost always shows the relationships to be much more complex than the examples above, as illustrated in the following diagram:

For example, the loudness of a sound is strongly correlated with the intensity of the sound wave. But if its frequency is high enough, it can’t be heard at all. Loudness, therefore, depends also upon frequency.

Expressing subjective quantities in objective terms is usually not simple. But it is important to try to make this our objective.

1.4 Sound

It has been said, “If a tree falls in the forest and there is no one to hear it, there is no sound.” Whether this is true or not depends upon one’s definition of sound. If sound is defined as “the sensation produced by stimulation of the organs of hearing,” the statement is true. If sound is defined as “the mechanical vibrations transmitted through an elastic medium,” like the air, the saying is false. This is an example of measurable versus perceptual interpretation. In this text, we will take the word sound to be perceptual (subjective). Where the distinction is important, we will use sound wave for the measurable (objective) descriptor. In many cases, the distinction is unimportant, and the word sound will cover both aspects.

Sound is one of the pollutants of our big cities today, as well as being ...