eBook - ePub

Principles of Emergency Planning and Management

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Principles of Emergency Planning and Management

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

David Alexander provides a concise yet comprehensive and systematic primer on how to prepare for a disaster. The book introduces the methods, procedures, protocols and strategies of emergency planning, with an emphasis on situations within industrialized countries. It is designed to be a reference source and manual from which emergency mangers can extract ideas, suggestions and pro-forma methodologies to help them design and implement emergency plans.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Principles of Emergency Planning and Management est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Principles of Emergency Planning and Management par en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Mathématiques et Théorie des jeux. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sujet

MathématiquesSous-sujet

Théorie des jeuxCHAPTER 1

Aims, purpose and scope of emergency planning

We are all part of the civil-protection process. Emergencies can be planned for by experts, but they will be experienced by the relief community and the general public alike. Therefore, we should all prepare for the next disaster as remarkably few of us will be able entirely to avoid it.

1.1 Introduction

This chapter begins with a few words on the nature and definition of concepts related to emergencies and disasters. It then offers some definitions and primary observations on the question of how to plan for and manage emergencies. Next, brief overviews are developed of the process of planning for disasters in both the short term and the long term.

1.1.1 The nature of disaster

For the purposes of this work, an emergency is defined as an exceptional event that exceeds the capacity of normal resources and organization to cope with it. Physical extremes are involved and the outcome is at least potentially, and often actually, dangerous, damaging or lethal. Four levels of emergency can be distinguished. The lowest level involves those cases, perhaps best exemplified by the crash of a single passenger car or by an individual who suffers a heart attack in the street, which are the subject of routine dispatch of an ambulance or a fire appliance. This sort of event is not really within the scope of this book, which deals with the other three levels. The second level is that of incidents that can be dealt with by a single municipality, or jurisdiction of similar size, without significant need for resources from outside. The third level is that of a major incident or disaster, which must be dealt with using regional or interjurisdictional resources. In comparison with lower levels of emergency, it requires higher degrees of coordination. The final level is that of the national (or international) disaster, an event of such magnitude and seriousness that it can be managed only with the full participation of the national government, and perhaps also international aid.

Although the concept of an emergency is relatively straightforward, disaster has long eluded rigorous definition.* In this work it will be treated as synonymous with catastrophe and calamity. Some authors prefer to define a catastrophe as an exceptionally large disaster, but as no quantitative measures or operational thresholds have ever been found to distinguish either term, I regard this as unwise. Generally, disasters involve substantial destruction. They may also be mass-casualty events. But no-one has ever succeeded in finding universal minimum values to define “substantial” or “mass”. This is partly because relatively small monetary losses can lead to major suffering and hardship or, conversely, large losses can be fairly sustainable, according to the ratio of losses to reserves. It thus follows that people who are poor, disadvantaged or marginalized from the socio-economic mainstream tend to suffer the most in disasters, leading to a problem of equity in emergency relief.

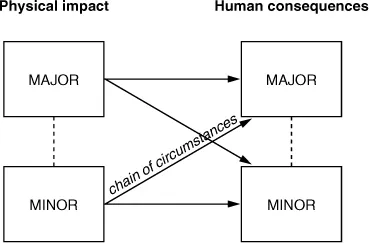

It is important to note that disasters always involve the interaction of physical extremes (perhaps tempered by human wantonness or carelessness) with the human system. There is not always a proportionate relationship between the size of the physical forces unleashed and the magnitude of the human suffering and losses that result. Chains of adverse circumstances or coincidences can turn small physical events into large disasters (Fig. 1.1). For instance, if a minor earthquake causes an unstable bridge to collapse, the consequences will be different if the bridge is unoccupied or if vehicles are on it.

Disasters involve both direct and indirect losses. The former include damage to buildings and their contents; the latter include loss of employment, revenue or sales. Hence, the impact of a disaster can persist for years, as indirect losses continue to be created. This obviously complicates the issue of planning and management, which must be concerned with several timescales.

A basic distinction can be made between natural disasters and technological disasters (see Table 1.1), although they may require similar responses. The former include sudden catastrophes, such as earthquakes and tornadoes, and so-called creeping disasters, such as slow landslides, which may take years to develop. In between these two extremes there are events of various durations; for example, there are floods that rise over several days, or volcanic eruptions that go on intermittently for months. Technological disasters include explosions, toxic spills, emissions of radio-isotopes, and transportation accidents. Riots, guerrilla attacks and terrorist incidents are examples of other forms of anthropogenic hazard that give rise to social disasters (Table 1.1). These will receive limited coverage in this book, which is mainly about coping with natural and technological incidents and disasters. Terrorism, riots and crowd incidents are germane because emergency personnel often have to provide back-up services and care for victims. However, such events are problematic in that, more than any other kind of eventuality, they risk compromising the impartiality of emergency workers, who may be seen as handmaidens of a group of oppressors, such as policemen or soldiers, who are in charge of operations.

Figure 1.1 Relationship between physical impact and human consequences of disaster. A minor physical event can lead to a major disaster in terms of casualties and losses if circumstances combine in unfavourable ways.

Table 1.1 Classes of natural, technological and social hazard.

Class of hazard | Examples |

Natural (geophysical) | |

Geological | Earthquake, volcanic eruption, landslide (including rockfall, debris avalanche, mudflow), episode of accelerated erosion, subsidence |

Meteorological | Hurricane, tornado, icestorm, blizzard, lightning, intense rainstorm, hailstorm, fog, drought, snow avalanche |

Oceanographic | Tsunami (geological origins), sea storm (meteorological origins) |

Hydrological | Flood, flashflood |

Biological | Wildfire (forest or range fire), crop blight, insect infestation, epizootic, disease outbreaks (meningitis, cholera, etc.) |

Technological | |

Hazardous materials and processes | Carcinogens, mutagens, heavy metals, other toxins |

Dangerous processes | Structural failure, radiation emissions, refining and transporting hazardous materials |

Devices and machines | Explosives, unexploded ordnance, vehicles, trains, aircraft |

Installations and plant | Bridges, dams, mines, refineries, power plants, oil and gas terminals and storage plants, power lines, pipelines, high-rise buildings |

Social | |

Terrorist incidents | Bombings, shootings, hostage taking, hijacking |

Crowd incidents | Riots, demonstrations, crowd crushes and stampedes |

Source: Partly based on table 4.3 on p. 101 in Regions of risk: a geographical introduction to disasters, K. Hewitt (Harlow, England: Addison-Wesley-Longman, 1997).

In reality, the distinction between natural and human-induced catastrophe is less clear-cut than it may seem: it has been suggested that the cause of natural catastrophe lies as much, or more, in the failings of human organization (i.e. in human vulnerability to disaster) as it does in extreme geophysical events.

1.1.2 Preparing for disaster

This book concentrates on planning and preparation for short-term emergencies: events that develop rapidly or abruptly with initial impacts that last a relatively short period of time, from seconds to days. These transient phenomena will require some rapid form of adaptation on the part of the socio-economic system in order to absorb, fend off or amortize their impacts. If normal institutions and levels of organization, staffing and resources cannot adequately cope with their impacts, then the social system may be thrown into crisis, in which case workaday patterns of activity and “normal” patterns of response must be replaced with something more appropriate that improves society’s ability to cope. As a general rule, this should be done as much as possible by strengthening existing organizations and procedures, by supplementing rather than supplanting them. The reasons for this are explained in full later, but they relate to a need to preserve continuity in the way that life is lived and problems are solved in disaster areas. There is also a need to utilize resources as efficiently as possible, which can best be done by tried and tested means.

Current wisdom inclines towards the view that disasters are not exceptional events. They tend to be repetitive and to concentrate in particular places. With regard to natural catastrophe, seismic and volcanic belts, hurricane-generating areas, unstable slopes and tornado zones are well known. Moreover, the frequency of events and therefore their statistical recurrence intervals are often fairly well established, at least for the smaller and more frequent occurrences, even if the short-term ability to forecast natural hazards is variable (Table 1.2). Many technological hazards also follow more or less predictable patterns, although these may become apparent only when research reveals them. Finally, intelligence gathering, strategic s...