eBook - ePub

Q&A Commercial Law

Jo Reddy, Rick Canavan

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 207 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Q&A Commercial Law

Jo Reddy, Rick Canavan

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Routledge Q&As give you the tools to practice and refine your exam technique, showing you how to apply your knowledge to maximum effect in assessment. Each book contains essay and problem-based questions on the most commonly examined topics, complete with expert guidance and model answers that help you to:

Plan your revision and know what examiners are looking for:

-

- Introducing how best to approach revision in each subject

-

- Identifying and explaining the main elements of each question, and providing marker annotation to show how examiners will read your answer

Understand and remember the law:

-

- Using memorable diagram overviews for each answer to demonstrate how the law fits together and how best to structure your answer

Gain marks and understand areas of debate:

-

- Providing revision tips and advice to help you aim higher in essays and exams

-

- Highlighting areas that are contentious and on which you will need to form an opinion

Avoid common errors:

-

- Identifying common pitfalls students encounter in class and in assessment

The series is supported by an online resource that allows you to test your progress during the run-up to exams. Features include: multiple choice questions, bonus Q&As and podcasts.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Q&A Commercial Law est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Q&A Commercial Law par Jo Reddy, Rick Canavan en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Law et Law Theory & Practice. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

1 | General Questions |

INTRODUCTION

This chapter contains four questions which are not confined to one particular part of the syllabus but are broader. Such questions are often included in examinations in order to test your knowledge of recent developments in the subject or simply to give you an opportunity, which most questions in law papers do not, to demonstrate a wider knowledge of the syllabus. The first question poses an important general question as to whether it is possible to define commercial law. Questions 1 and 2 are of a general type often found in examinations, inviting the student to take an overview of commercial law and its function in the business world. Question 3 requires a good knowledge of the recent Consumer Rights Act 2015.

QUESTION 1

‘No matter what impression may be given by textbooks, there is no such thing as English Commercial Law. There are only a number of loosely connected areas of private law, which are lumped together and called “Commercial Law” without any thought given to whether or not they form a coherent area of law.’

How to Answer this Question

This is a challenging question and one to which there can be no definitive answer. This is because commercial law means different things to different textbook authors. We do not know why some topics are included while others are not dealt with or are categorised as being only ‘ancillary’ to commercial law.

The problem we face is that England does not have a self-contained body of principles and rules specific to commercial transactions. English commercial law has been developed by common law, and its principles are all over the place in case reports. It is almost impossible to rely on law reports alone. We depend on academic textbooks, practitioner texts and journals but such materials do not form a commercial code. Authors do not create law; they merely explain it. Students need to set their own boundaries in answering this question and the challenge is to engage in the discussion rather than striving to a conclusion as to its definition.

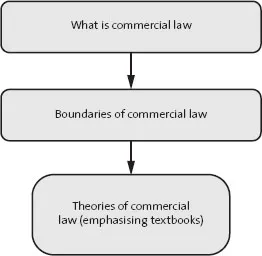

Applying the Law

ANSWER

The reason why textbooks do not and cannot provide a definition of commercial law is because the UK does not have a code. It does not have a self-contained integrated body of principles and rules specific to commercial transactions (unlike the American Uniform Commercial Code). It is the absence of anything resembling either a commercial code or the commercial part of a civil code which makes defining the boundaries of commercial law difficult. Defining commercial law by looking at the approach taken by textbooks is over-simplistic. The obvious problem with defining commercial law in this way is that we do not know why some topics are included while others are not dealt with or are categorised as being only ‘ancillary’ to commercial law. Most commercial textbooks do not try to define commercial law; they do not set out the theories of commercial law.

Different commercial textbooks contain different topics. The various topics however reveal an enduring theme. In all aspects of commercial law, the focus is on transactions. Some commercial law (for example, sale of goods) regulates transactions directly. Other areas (for example, banking and insurance law) concern mechanisms necessarily ancillary to such transactions. Others (for example, product liability) stem from the consequences of transactions even where the party seeking the help of the law is not a direct party in the transaction.

But the selection of topics depends on authors’ ideas of what business activity is. Perhaps authors are not sure where some topics should be placed. Most commercial law courses are a sort of ‘miscellaneous section’, that is, topics put together because they do not fit conveniently into courses of their own (unlike, for example, company law, revenue law).

In any event, the textbook approach gives rise to boundary problems. Authors draw boundaries in different ways. For example, Professor Goode limits boundaries of commercial law to law that governs commercial transactions (for example, contract law, sale of goods). He excludes the law governing commercial institutions (for example, company law and partnership law). The difficulty with this is that the boundary between transactions and institutions is not clear. It is arguable, for instance, that the Companies Act 2006 is no more than the application of general agency principles (and so is transactional law and, yes, qualifies as commercial law). Equally arguable is that the Companies Act is crucial to the structure and function of companies (and so classifies as institutional law).

CONCLUSION

Taking a textbook approach to defining commercial law is over-simplistic. If we take the textbook approach, then commercial law is predominantly doctrinal (or ‘black-letter’) in its methodology and orientation. All we can say is that commercial law textbooks reinforce ideas about what commercial law is. But the selection of topics depends on authors’ own ideas of commercial law and what business activity is. The obvious problem with defining commercial law in this way is that it is subjective.

QUESTION 2

‘The strength of English commercial law has been its concern to provide solutions to practical problems facing commercial parties.’

How to Answer this Question

This question is not an opportunity to discuss commercial law in a general way. A good answer requires you to identify what the needs of the commercial community are and then identify how the courts and legislature have responded to those needs. You should illustrate these points by drawing examples from a range of areas of commercial law.

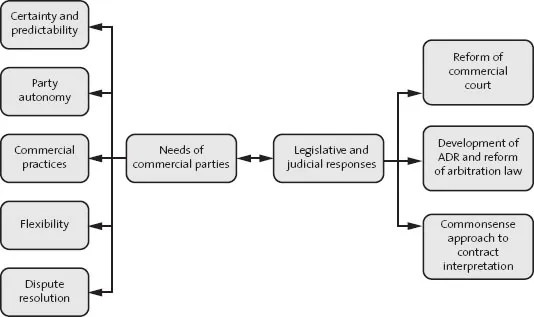

Applying the Law

This diagram illustrates the main factors to consider for both commercial parties and possible legal responses.

ANSWER

In order to answer the question, it is necessary to identify what problems commercial parties face and how English commercial law helps them by providing solutions. If commercial law is about commercial activity, then the fundamental purpose of commercial law is the facilitation of commercial activity.1

(1) CERTAINTY AND PREDICTABILITY

The commercial community values legal certainty above all.2 Business people want to know that courts will be reliable and will consistently interpret transactions in a particular way. This allows for planning and anticipation of liability. Many transactions (many of high value) are undertaken on the basis that courts will continue to follow rules laid down in preceding cases. Business people do not want the law to be based on a random application of local custom and idiosyncrasies of individuals. Of course, this is not guaranteed because judges’ thinking will change over time but, on the whole, courts have consistently promoted certainty of outcome over those of fairness and justice. This is what business people want.

As Lord Mansfield said, it is more important that a rule is certain than what the rule is.3 An example is the postal rule (Adams v Lindsell (1818)). It does not matter if acceptance is deemed to take place at the time of posting or receipt. Parties to a contract merely need to know.

If the law is clear and certain, the outcome of a dispute may be predicted and parties may resolve it without having to litigate. If litigation is necessary, at least disputes can be dealt with quickly. This is especially important in a price fluctuation market.

The use of documentary credits is an example of courts’ approach to ensure certainty.4 Documentary credit is a bank’s assurance of payment against presentation of specified documents. It is the most common method of payment in international sales. Although the Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits5 only applies if it is expressly incorporated into a contract, because of its wide acceptance amongst international bankers, courts are likely to view the UCP as impliedly incorporated as established usage. There are two general principles involved with documentary credits. First, the doctrine of strict compliance dictates that a banker must comply exactly with its client’s (the buyer) instructions as to payment. Even if the value of some documents required by the buyer is questionable, ‘it is not for the bank to reason why’.6 Even a minor discrepancy will disentitle the banker to reimbursement from its client. A clear example is the case of Equitable Trust v Dawson (1927) where the buyer’s instruction was payment against a certificate signed by experts, whereas the banker paid against documents signed by one expert. The House of Lords held that the banker had acted against his instructions and was thus not entitled to reimbursement.7

Second, the principle of autonomy of credit dictates that a bank is not concerned with any dispute that the buyer might have with the seller. As Lord Denning said8 in Power Curber v National Bank of Kuwait (1981), a letter of credit ranks as cash and must be honoured. Courts have consistently defended the autonomy principle on grounds that an irrevocable letter of credit is the ‘life-blood of international commerce’. It thus must be honoured and be free from interference by the courts, otherwise trust in international commerce would be damaged. The commercial value of the documentary credit system lies in the fact that payment under a letter of credit is virtually guaranteed (subject to the strict compliance principle). Certainty of payment is of paramount importance to the business community, thus irrevocable credits are treated like cash by courts.

(2) PARTY AUTONOMY

Business people should be free to make their contracts and they are entitled to receive what they bargained for. The aim of commercial law is to enforce the intention of the parties, not frustrate that intention by a rigid set of rules.9

Courts take a non-interventionist approach, justified on the basis that it promotes certainty. Courts should only intervene if the contract terms are so restrictive or oppressive that it offends public interest. Whenever there is a contest between contract law and equity in a commercial dispute, contract law wins hands down. This is one reason why so many foreigners select English law to govern their contracts and English courts to decide the case. Business people know where they stand with English law and English judges.10

Courts are, however, encouraged to take a more interventionist approach in some types of contracts. This is because of the development of a ‘consumer society’. For example, although the Consumer Rights Act 2015 (‘CRA’)11 serves primarily to consolidate much of the existing law in one statute, it does make significant changes to the law in some areas. Overall, the Act represents a substantial increase in the rights of consumers and in the powers of the court. Business-to-business contracts are kept separate, however, and the Sale of Goods Act 1979 continues to govern the relationship. There is now a clearer difference between ...