![]()

CHAPTER 1

Inscribing the Island

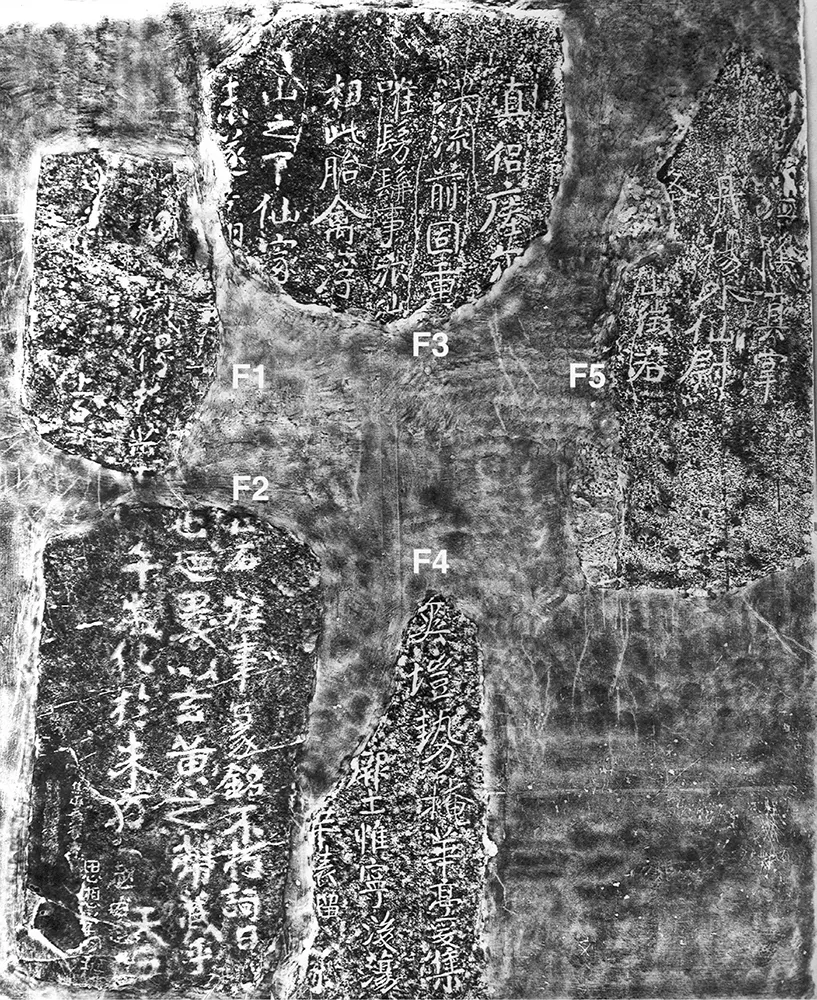

In 2018, there were about 780,000 visitors to the small island of Jiaoshan.1 Many of them were calligraphy lovers who came to worship the stone carving of Eulogy for Burying a Crane. Housed in a traditional-style building in the garden of the Jiaoshan Stone Inscription Museum, the five fragments are pieced together in a kind of faux cliff intended to approximate the appearance of the original site (plate 2, figure 1.1). To help the visitors see the characters in the dim lighting, each stroke is filled in with white plaster.

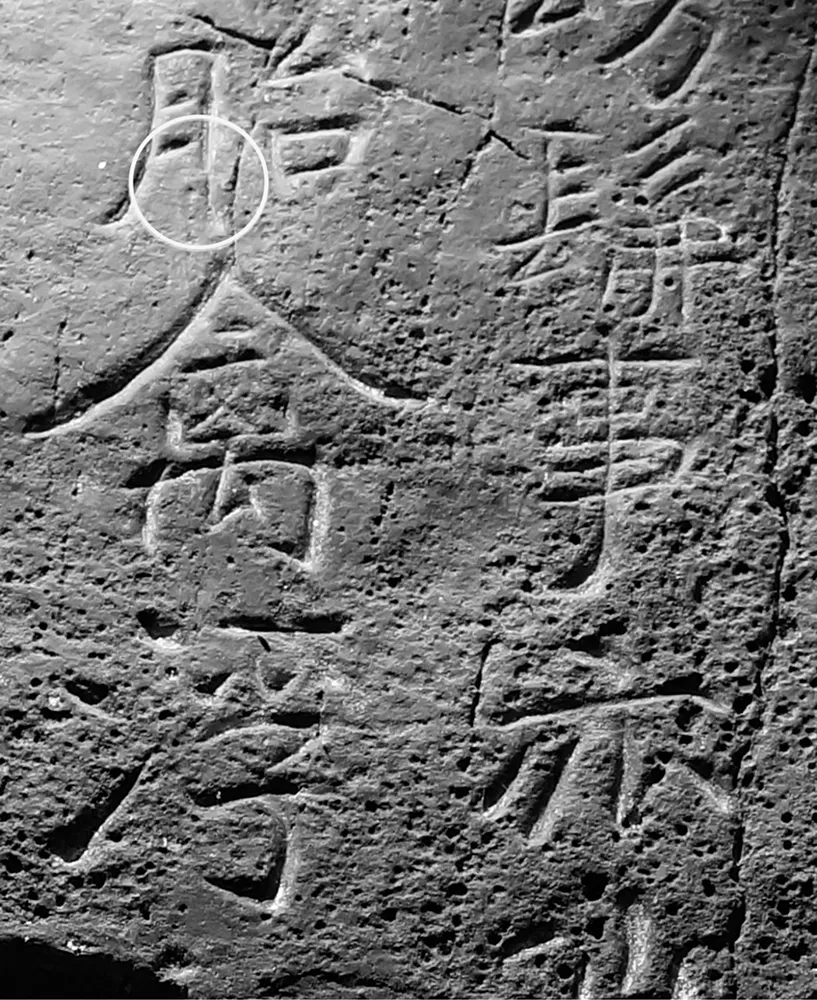

Despite its dilapidated status and large size (approximately 235 × 204 cm), it is clear that the rectangular layout was like that of stone epitaphs from medieval China. However, unlike the characters on those artifacts (or those on freestanding stone steles, which are carefully polished before the writing is added), the characters were carved directly into the rough surface of the unquarried rock. The calligrapher adapted the characters to the irregularity of the stone, making some larger than others and avoiding a strict regularity of columns or rows. Whereas some characters show clear strokes, others display odd shapes that make the viewer wonder if they reveal the original brushwork or are rather the result of natural erosion or numerous campaigns of recarving and alteration. Still, it can be ascertained that the strokes were carved from the two edges, creating a wide-open V-shaped groove on the stone, as shown in figure 1.2.

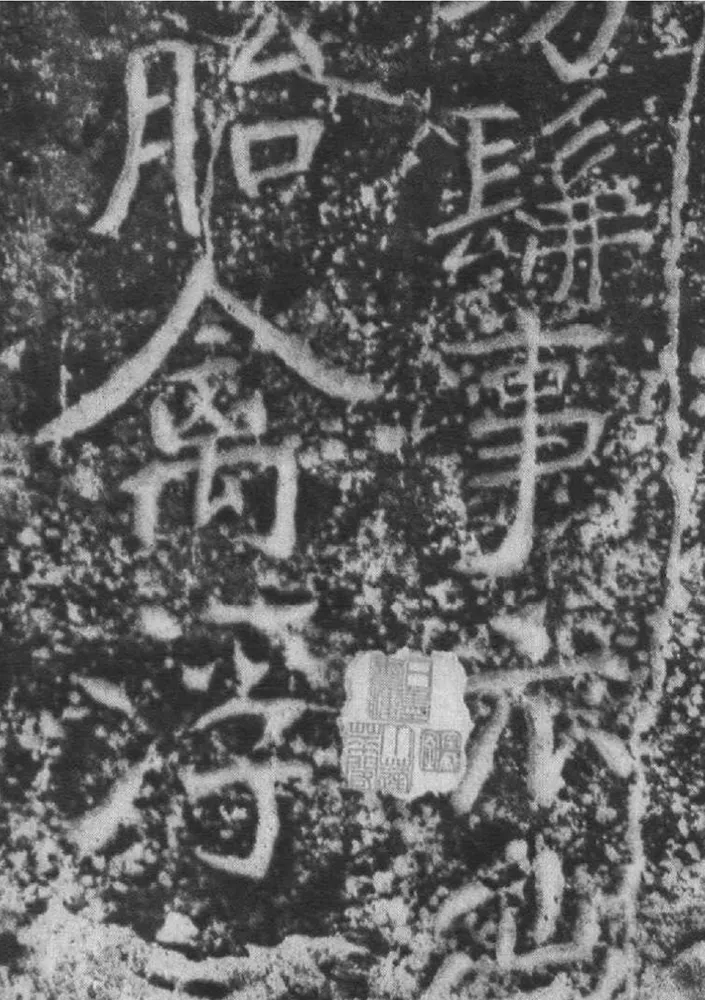

These fragments, traditionally numbered one through five (hereafter noted as F1–F5, as marked on the rubbing in figure 1.1), vary in size, shape, and texture. F1 (plate 3), the smallest stone, has lost most of its characters and shows many signs of scraping and other abrasions. F2 (plate 4) is rectangular and has a relatively smooth surface; the carving of the characters on this fragment is shallower than that on the other stones, which makes some scholars suspect that it was a later recarving. F4 (plate 6) presents the same problem and has the most irregular surface, marked by several deep indentations. Characters are deeply carved and possibly the result of late modification. F3 (plate 5) and F5 (plate 7) appear quite different in texture from the other fragments. Numerous tiny pockmarks on their surfaces (figure 1.2) show the effects of natural erosion that are often found on limestone (similar to those on the porous Taihu stones that adorn traditional Chinese gardens). Although it is reported that the inscription was heavily damaged after it was removed from the water in 1713 (see conclusion), F3 and F5 seem well preserved; the location and shapes of dents and pores match their traces (referred to as “stone flowers” by rubbing connoisseurs) left on the early rubbing (figure 1.3; see full image in figure C.9), which is arguably dated to the Song dynasty.2

FIGURE 1.1. Overview of Eulogy for Burying a Crane. Ink rubbing, approx. 235 × 204 cm. Courtesy of Jiaoshan Stone Inscription Museum. The numbers F1–F5 refer to the extant fragments.

FIGURE 1.2. Detail of Fragment no. 3 of Eulogy for Burying a Crane. The circle indicates the worn strokes discussed in the text.

Even so, the engraved strokes are hardly intact. Take the example of the character tai 胎, which appears complete and crisp on the rubbing. On today’s stone, however, the bottom of the shu stroke in the yue 月 radical (figure 1.2, marked with a circle) is almost worn away. Oddly enough, the top section of the same stroke is still deeply carved, even lower than the worn area—very likely a result of rechiseling. The modification even causes the entire yue radical to pull away a little from the right radical. Looking closer at the yue radical, one can find traces of modification in the double lines at the bottom of the pie stroke (figure 1.2). Whereas these possible modifications (and even alterations) may not affect our reading of the text, we shall proceed with great caution in the discussion of the “original” stone of the Eulogy—indeed, of any original stones of famous monuments from ancient times. Instead, our analysis of the calligraphy will be based mainly on the rubbing images, even though they are not free from similar problems.

FIGURE 1.3. Rubbing of Eulogy for Burying a Crane. Detail. Palace Museum, Beijing. From Zhongguo meishu quanji: Shufa zhuanke bian 2:142.

The Text: Reconstruction and Translation

The ninety total characters on the extant stones (including twelve partly damaged characters) constitute only about two-thirds of the original inscription (plate 8; early accounts report characters in yellow that no longer survive on today’s fragments). Other characters in the chart were reconstructed by Zhang Chao (1625–1694) and Wang Shihong, the latter of whom combined the characters extant in his time with an earlier reconstruction of the text, said to have been made before the stones completely fell into the river (see the concluding chapter for details). Some characters (noted in the translation below and also marked in red in plate 8) were added to make the text coherent, but these were pure speculation.3 The inscription reads from left to right, a format unusual but not unique in traditional Chinese writing. Full of literary allusions and tropes, the text is cryptic to modern readers without annotations, and the fragmentary status only increases the challenge of reading:

1Eulogy for Burying a Crane, with Preface

Composed by the Perfected Recluse of Mount Huayang4

in the calligraphy of the Woodcutter of Mount Shanghuang5

No one knows the age of this crane.

5I acquired him in the year renchen6 in Huating.7

He transformed in the year jiawu at Zhufang.8

Did Heaven not allow me to soar about the cosmos as I wish?9

Why take away the crane so quickly?

I therefore wrapped him in [Daoist ceremonial] black and yellow silk10

10and buried him at the foot of this mountain.

The immortals do not hide . . .11

. . . my . . .

I then set up a stone to honor his virtues

and carved a eulogy so that the crane will not be forgotten.

15The eulogy reads,

To judge the physiognomy of the “viviparous bird,”12

[The immortal] Master Fuqiu wrote the Crane Classic.13

I do not wish to say anything more.

You [the crane] have hidden the spirit.14

20At the Thunder Gate you departed the drum;15

on the huabiao pillars you left behind your shadow.16

The meaning is obscure and subtle;

these events are elusive and mysterious.17

Where is it that you will go?

25Released and transformed18 . . .

to the west bamboo grove, the sacred place.19

The land is quiet and peaceful.20

Behind flows the raging torrent;

in front stand firmly the double-layered gates.21

30The left side reaches to the Kingdom of Cao;22

the right side is fenced with a thorny gate.23

The shady side of the mountain is dry and lofty.

The height of the place overlooks Huating [the crane’s home].24

Therefore, I have gathered my perfected companions,25

35buried you here, and written this eulogy.

The Recluse of Mount Jiang26

The Outer Immortal Commandant of Danyang27

The Perfected Steward of Jiangyin.28

(1A)29

At first glance, the literary form of the Eulogy text is no different from that of countless medieval epitaphs surviving today. It opens with the title and the name of the author (though the calligrapher is rarely mentioned in other cases). Next comes a prose biography of the deceased, here the crane (lines 4–10). The prose section is followed by a eulogy in tetrasyllabic verse praising the bird by likening it to notable cranes of antiquity (lines 15–24). The Eulogy closes with the description of its landscape setting (lines 25–33)—an indispensable part of an epitaph to announce the safe and auspicious burial location to both the living and the underground world. What would be unusual for a common epitaph is the names of three witnesses who presumably attended the burial (lines 36–38).

Traditionally, scholars have read this poem as evidence that Daoists actually buried and mourned a pet crane at the foot of Jiaoshan. Based on this assumption, they have spilled much ink decoding place names and aliases in the text, confident that—in spite of its strangeness—the carving was a real epitaph for a real crane. This assumption, however, more or less overlooks the place of the Eulogy within the history of early medieval Chinese literature and material and visual culture.

The complex allusions and poetic language mark the text as part of a tradition of writing about birds and other animals as a way to metaphorically express feelings about human misfortunes. The “epitaph” also appropriates medieval funerary objects in multiple dimensions; the text may be read as a literary parody imitating mortuary writing, while the physical form, though appropriating that of entombed medieval epitaphs, distinguishes itself from a real epitaph by its public visibility. Furthermore, the placement of this unprecedented epitaph near the base of Jiaoshan took advantage of the topography of t...