This book discusses the case for integrating informal learning in the daily life and work of schools. The recognition of informal learning is a step towards understanding that learning takes place in multiple ways, even before birth and throughout the life cycle. It can take place anywhere, anytime and anyhow. It is an essential feature of the human fabric. This creates a new educational challenge: Integrating formal and informal learning in schools in order to build social relationships and knowledge platforms that can meet the challenges of the 21st century.

The aim of this introductory chapter is to offer conceptual tools that help to define informal learning from different perspectives. The purpose is to enhance the school as a social institution that recognizes multiple sources of learning in the creation of knowledge. The following spaces of reflection will be discussed:

The nature of informal learning

Learning is best seen as a natural human ability. The formation of society and the building of human capacity have been possible due to the continuous acquisition of knowledge. Yet knowledge in official school curricula focuses not on this natural learning process but on specified subjects and disciplines that are sanctioned by authorities. Natural learning, or everyday learning, that is not part of “official learning” tends to be seen as “informal”: Creativity, entrepreneurship, problem solving and empathy, among other metacognitive abilities, have until recently not been recognized by the school system.

The precise specification of informal learning is difficult because it is embedded in daily social processes such as belonging to a community, social movements, gender identification, families, community regeneration, justice, health, leisure, etc. The ethical qualities of this kind of informal learning are clear and are part of the intellectual profile of each human being and their lived experiences. At the same time, antisocial, xenophobic and violent behaviours are also often acquired informally and the elimination of such learning is an important role for schools.

The processes of acquiring informal learning involve basically personal experience and social influence: Observations focused on self-interest, reflections on misconceptions and successes, imitation and adaptation into a diversity of social groups, dialogue and languages between adults and children, social speech such as aesthetics or fashion, social networks, peer communication, collaboration between peer groups, etc. These processes of “natural learning” are often conceptualized in school contexts as active learning methods, and this concept starts to recognize the importance of informal learning.

The conceptual foundation of active learning methods is simple: Neither students nor teachers are symbolic institutions seeking rewards based on hierarchical position or institutional prestige (Weber, 1905). Rather, the basic assumption of this book is that both students and teachers are considered actors (“understood as human beings with their beliefs, feelings and emotions in their rationality”) (Alpuche de la Cruz, 2015) capable of autonomous individual action. The justification of this basic assumption, focused on the freedom of individuals, represents a critique of social determinism favoured by functionalist approaches, where the origin and social context of each individual determines the itineraries and school destinations of students.

The concept of social relationship is implicit in informal learning. That is, learning (both formal and informal) is acquired through social relationships in which different human beings exchange meanings, complement knowledge, create new categories of or build necessary symbols to undertake communication processes. They may also engage in other actions which provide opportunities for mutual influence among different organizational actors in an institutional framework, such as schools.

The effects of autonomy of thought and social relationships among organizational actors are consistent with the idea of pragmatic complexity in schools (Ansell & Geyer, 2016; Cilliers & Greyvenstein, 2012). The central idea is that the interactions of organizations (and their members) with different local and global environments constitute self-organized learning spaces that consist of unique practical spaces of information as well as knowledge. Such spaces have their own “boundaries” that define the scope where each subject acquires his or her formal and informal learning. The organizational complexity lies in the fact that as far as schools are concerned, formal school subjects or specific groups of subjects have their own learning spaces compatible with the common space of the school as an institution. Such norms and rules characterize schools and will govern exchanges between formal and informal learning to reflect a particular organizational culture.

An organizational culture that encourages informal learning values the autonomy of different school actors who can express the diversity of their experiences learned, inside and outside the school space. All forms of knowledge should be the object of merit and appreciation within the social and cultural framework of each school space. This includes the formal curricula and the informal learning acquired by each student, with both being assessed. This double reality of value and merit constitutes the basis of social justice in the processes of schooling. This requires a balance between recognizing the objective value of acquiring available knowledge for each subject as well as giving credit for the acquisition of informal learning that takes place in the particular social and cultural contexts of the school and its community (Guba & Lincoln, 1994).

Schools as cultural organizations are characterized by the complexity of social relationships among their members, always subject to an exchange of meanings via the basic technology of institutional functioning: Teaching and learning. Additionally, reflective actions taken by the users themselves will always add value to formal learning (Adams & Gupta, 2017; Scheerens, 2011). Schooling is not a one-way process. Both students and teachers will reflect on the purposes of the organizations of which they are a part and the goals the organization has for them, and they may (or may not) modify them in terms of their individual objectives and purposes (Blaschke & Stewart, 2016).

What is informal learning?

The most common definition has been proposed by Livingstone (1999):

any activity involving the pursuit of understanding, knowledge or skill which occurs outside the curricula of educational institutions, or the courses or workshops offered by educational or social agencies. (p. 51)

This definition has some shortcomings: It defines informal learning outside the institutional context, and it excludes the exchange between formal and informal learning. Other approaches locate the definitions of informal learning in more qualitative terms. For example, Michael Eraut (2004) proposed several definitions of informal learning. He focused on the education of adults, his raison d'être being that different cognitive actions shape the awareness of different organizational actors in different social environments: Memory of events, selection of information, building of expectations, reflection, focus of interest, recognition of important events, discussion, personal involvement in actions and strategic planning of actions. In this conceptual framework, informal learning includes the experiences that are acquired and learnt by subjects throughout the development of their own lives. This appeal to individual freedom is key in order to define informal learning: It is the unique and personal learning which is acquired by adults. Other approaches classify informal learning from the focus of the subjectivity of each organizational actor based on two variables: Intentionality and consciousness (Van Noy, Jacobs, Korey, Bailey, & Hughes, 2008; Van Noy, James, & Bedley, 2016). In other words, it is the learning of and from life that is distributed in the different actions undertaken by individuals in the social and cultural contexts in which they live (Foley, 1999).

Factors contributing to the development of informal learning in schools

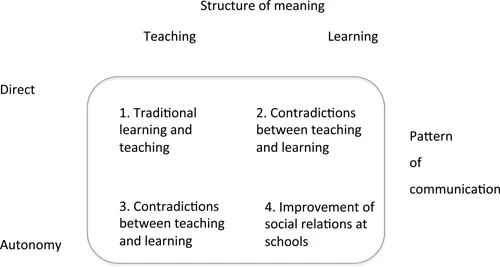

According to neo-institutional theories, meaning structures and communication patterns are the framework for basic analyses of organizations. The structures of meaning (norms and rules) refer to the grammar or organizational language that prevails in each school. These involve the universe of concepts used by school members, the symbols used to establish feelings of belonging to a common reality, the rituals used to control organizational habits and the beliefs established to regulate the social order that allows the continuity of the school year with its regulatory characteristics. Communication patterns refer to the social climate that allows or prevents social relationships in schools; for instance, mutual trust, citizenship rights in schools, feeling of responsibility and belonging.

A neo-institutional organizational perspective

From a neo-institutional perspective, “structure of meaning” and “pattern of communication” provide the basic framework for explaining the organization of schooling. This framework regulates the organizational grammar of schooling. “Structure of meaning” refers to the interpretive processes of teachers and students in all aspects of school education. “Pattern of communication” refers to the social relations in which different school actors exchange knowledge and information related to formal and informal curriculum. A “direct pattern of communication” is characterized by the recognition of some level of hierarchy between information senders (usually teachers) and beneficiaries (usually students). This is how much traditional teaching and learning takes place. An “autonomous pattern of communication” acknowledges that from time to time actors in the education process will switch their roles from information senders to beneficiaries, regardless of their identity as a teacher or a student (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Structure of meaning and pattern of communication.

Traditionally, synchronizing the patterns of communication between different education actors has been regarded as a matter of efficiency. The maintenance of hierarchy in education relationships has also been regarded as a disciplining technique that creates a social distance between teachers and students. A contrary education organizational concept is being highlighted in this chapter. It is based on an education environment where all actors adopt autonomous patterns of communication. Transactions and responsibilities are assumed by all school actors, who consequently acquire cultural agency in schools. This concept will improve social relations among all actors who constitute a school. All members have the ability to create knowledge and produce content that is important for themselves as well as for other individuals or social groups.

The key for effectively developing this model is the creation of a “learning framework.” This is an institutional process by which norms and rules of learning are fixed in each school site. It identifies the cognitive processes that are going to be recognized, validated and certified by a school community. Schools that are focused on their own “learning framework” develop a sense of ownership over it and value communication patterns based on dialogue and cooperation. Such schools are characterized by the creation of social capital creating stable learning environments characterized by educational qualities that are focused on reflective action, trust, social solidarity, feeling of belonging or collective action. This learning environment symbolizes the school reality where students and teachers together develop their learning activities. Beyond the physical space of each school there are new school “boundaries” that include informal learning as an important reality of schooling in this new educational system.

Impediments and limitation of informal learning

The consideration of students as having organizational agency is an ideal model that creates new social relationships needed to produce new knowledge which is broader than the academic knowledge prescribed in mainstream educational systems (Jeffs & Smith, 1990). One step forward for this institutionalized curriculum is the diversification of learning sources and the legitimation of learning acquired in the classroom and extracurricular activities. Yet this still maintains student dependency with regard to curricular prescriptions of the educational system. This raises the issues of what can be regarded as “authentic learning.”

There are different views. Two conceptual tendencies can be identified in authentic learning. One is pragmatic (transfer of knowledge) and the other is practical (participation of students and teachers in real-life issues, as referents of knowledge). From the point of view of the transfer of learning to other different situations based on classroom experiences, school systems are currently in charge of this transfer task. On the other hand, there are those who defend the symbolism of real-life experience as the main source of learning, the result of daily practice, symbolized in the liberal myth of the self-made person (Renner, Prilla, Ulrike, & Joachim, 2016). In other words, authentic learning from this perspective is based on a need to learn something to cover a personal or collective demand. This is the case of the self-employed worker who learns languages in his adult age to serve clients who demand his/her services, or the student who learns a sport in order to be part of a group and feel like a member of such group.

In fact, these two approaches of authentic learning are complementary. The reason behind such complementarity is the following. On the one hand, teachers learn their profession through real life, that is, in the process of their daily work. On the other hand, students learn through simulation, that is, through problem solving and practical examples that could be applied to their professional futures. “Authentic learning,” in this view, is reflected in the complementarities between formal and informal learning (Annen, 2013) whose boundaries can be regarded as liquid. That is, the different learni...