1.1 Is There a Crisis?

The penal system is in a state of crisis.

This might not seem a controversial claim. Nor would most people in this country imagine that this ‘penal crisis’ is either new or sudden. For many years, media reports have acquainted everyone with the notion that rocketing prison populations, overcrowding, unrest among staff and inmates, escapes and riots and disorder in prisons add up to a severe and deepening penal crisis. The term ‘crisis’ has been common currency in both media and academic accounts of the penal system for over 30 years now; the word recurs in newspaper headlines and in the titles of academic books and articles (for example Bottoms and Preston, 1980). Evidence for the existence of a crisis seems to be constantly in the news. Recent years have seen – to mention just a few out of many possible illustrations – the then Justice Secretary (Chris Grayling) having to deny the existence of a crisis in 2014 following a highly critical annual report from the Prisons Inspectorate (HMIP, 2014a); the Ombudsman condemning ‘the wholly unacceptable level of violence’ in prisons in 2016 (Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, 2016: 1); the President of the Prison Governors’ Association publishing an open letter in 2017 claiming that prisons were in crisis (Guardian, 2 August 2017); prison officers taking industrial action; an Urgent Notification Procedure being introduced in November 2017 in an effort to resolve serious and pressing issues in prisons; the head of the prison service being told to step down early as a result of the prisons crisis (Guardian, 20 September 2018); damning reports from the House of Commons Justice Committee, the National Audit Office and the Chief Inspector of Probation about the disastrous results of the government’s privatization of probation services (House of Commons, 2018; HM Inspectorate of Probation, 2019; National Audit Office, 2019); and another report from the House of Commons Justice Committee condemning ‘an enduring crisis in prison safety and decency that has lasted five years’ (House of Commons Justice Committees 2019: 6). All of this comes against the background of a prison population which continues at near record levels, considerable cuts in budgets due to the response to the financial crisis of 2008, what seems like a never-ending succession of Justice Secretaries (six including Kenneth Clarke since 2012) and a continuing deep malaise running through the penal system as a whole.

Yet is it really a ‘crisis’? Perhaps few would dispute that the penal system has serious problems – but is it really in a state of crisis? Then again, how long can a crisis last while remaining a crisis rather than business as usual? Surely there is something paradoxical in claims that the crisis has lasted for decades, or even (as was once said) that the system has been ‘in a perpetual state of crisis since the Gladstone Committee report of 1895’ (Fitzgerald and Sim, 1982: 3).

If to be in crisis means that the whole system is on the brink of total collapse or explosion, then we probably do not have a crisis, although with regard to the probation service we could be closer to this than we have ever been. And it should not be forgotten that when systems do collapse or explode – like the communist system in Eastern Europe in the late twentieth century, or the system of order within Strangeways Prison immediately before the historic riot of April 1990 – they can do so very suddenly. But it can be validly claimed that there is a crisis in at least two senses, identified by Morris (1989: 125). First, we have ‘a state of affairs that is so acute as to constitute a danger’ – and, we would add, a moral challenge of a scale which makes it one of the most pressing social issues of the day. Second, we may be at a critical juncture, much as a seriously ill person may reach a ‘turning point at which the patient either begins to improve or sinks into a fatal decline’. In other words, either the present situation could be used as an opportunity to reform the system into something more rational and humane, or else it will deteriorate into something much worse even than the present. In this book we will be using the ‘C-word’ in these senses to refer to the present penal situation in England and Wales, albeit with slight embarrassment and the worry that it has been used so often and for so long that there is a danger that it may be losing its dramatic impact.

Whether or not we choose to use the word ‘crisis’, what are the causes of the state the penal system is in, and how do its different problems relate to each other?

1.2 The Orthodox Account Of The Crisis

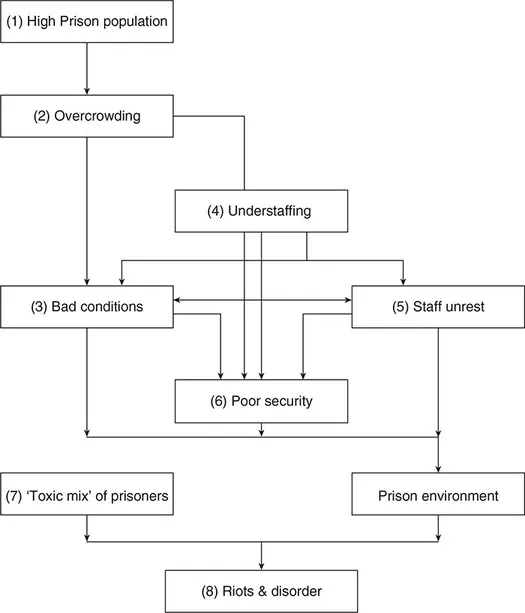

The orthodox account of the penal crisis is probably still the kind of commonsensical analysis underlying most mass media reports of problems in the penal system. At least until Lord Justice Woolf’s 1991 report into the Strangeways riot (Woolf and Tumim, 1991) versions of it were also regularly found in official reports purporting to explain phenomena such as prison disturbances. It is well summarized by the following extract from an old newspaper article entitled ‘Why the Prisons Could Explode’ (Humphry and May, 1977):

Explosive problems remain in many of Britain’s prisons – a higher number of lifers … who have nothing left to lose; overcrowding which forces men to sleep three to a cell and understaffing which weakens security. Prisons, too, are forced to handle men with profound psychiatric problems in conditions which are totally unsuitable.

This passage gives us almost all the components of the ‘orthodox account’ of the penal crisis. The crisis is seen as being located very specifically within the prison system – it is not seen as a crisis of the whole penal system, or of the criminal justice system, let alone as a crisis of society as a whole. The immediate cause of the crisis is seen as the combination of different types of difficult prisoners – what has been called a ‘toxic mix’ of prisoners – in physically poor and insecure conditions which could give rise to an ‘explosion’.

The orthodox account points to the following factors as implicated in the crisis:

- the high prison population (or ‘numbers crisis’);

- overcrowding;

- bad conditions within prison (for both inmates and prison officers);

- understaffing;

- unrest among the staff;

- poor security;

- the ‘toxic mix’ of long-term and life sentence prisoners and mentally disturbed inmates;

- riots and other breakdowns of control over prisoners.

Figure 1.1 The orthodox account of the penal crisis

These factors are seen as linked, with the last one – riots and disorder – being the end product that epitomizes the state of crisis. Figure 1.1 shows how the different factors interact according to the orthodox account. The high prison population is held responsible for overcrowding and understaffing in prisons, both of which exacerbate the bad physical conditions within prison. The combination of poor conditions and inadequate staffing has an adverse effect on staff morale, causing unrest which (through industrial action, for example) serves to worsen conditions still further. The four factors of bad conditions, overcrowding, understaffing and staff unrest are blamed for poor security, which is another factor contributing to the unstable prison environment. Finally, the combination of the ‘toxic mix’ of prisoners with these deteriorating conditions within which they are contained is thought to trigger the periodic riots and disturbances to which the prison system is increasingly prone.

We do not believe that the orthodox account provides a satisfactory explanation of the crisis, for reasons we shall be giving shortly. But most of the factors identified by this account are real and important, as we shall now detail.

The High Prison Population (The ‘Numbers Crisis’)

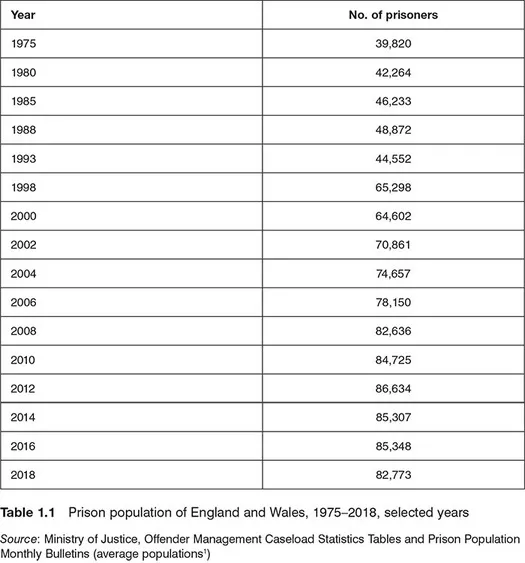

Table 1.1 Source: Ministry of Justice, Offender Management Caseload Statistics Tables and Prison Population Monthly Bulletins (average populations1)

It is widely agreed – although perhaps not by all politicians – that the number of prisoners in England and Wales is alarmingly high. It has also, until relatively recently, been rapidly rising. Table 1.1 shows how (despite occasional dips), the prison population rose to 86,000 in 2012 from under 40,000 since 1975 (a time when prison numbers were already causing serious concern) and has almost doubled since 1993. The prison population reached its highest ever peak so far of over 88,000 in December 2011, but has declined slightly in the past two years. Official Home Office projections estimate that by 2023 the prison population could increase by 3,200 (Ministry of Justice, 2018a).

There are several factors involved in this increase in prison numbers in recent years. In Chapter 4 we discuss the relationship between some of these factors, and conclude that the most crucial is the pattern of decisions by the courts. The most important of these is the sentencing decision – whether convicted offenders should be sent to custody and, if so, for how long – which we call ‘the crux of the crisis’. These court decisions can in their turn be greatly influenced by government policies, actions and rhetoric. As we stated briefly in the Introduction (section I.2) and detail further in Chapter 10 (section 10.2), for a long time both Conservative and Labour governments generally attempted to keep the size of the prison population under control by a mixture of legislation, executive action and exhortations to courts. However, from 1993 onwards John Major’s Conservative administration reversed this stand and pursued policies whose explicit aim was to increase the numbers of people in prison, with Home Secretary Michael Howard famously declaring in 1993 that ‘prison works’ to control crime. The ‘New Labour’ administrations of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown (1997–2010) may have dropped the slogan ‘prison works’, but showed little interest in trying to reduce custodial sentences; indeed, Labour Home Secretaries repeatedly called for tougher sentences for a wide range of offenders. Not surprisingly, therefore, the prison population rose to even greater heights under New Labour and the same trend continued under the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition government despite attempts by Justice Secretary Kenneth Clarke to turn the tide. The rate of increase in prison numbers did slow in 2010–2011, but the situation altered rapidly and drastically in August 2011 as the courts began dealing with defendants charged with offences connected with the urban riots of that month. With the explicit encouragement of Prime Minister David Cameron, sentencers imposed harsh and widely criticized sentences on rioters and looters, and magistrates remanded large numbers in custody to await trial at the Crown Court, thereby pushing prison numbers to their new peak of 88,485 in December 2011. Since then, while there has been a slight drop overall, alongside an increase of 26 per cent in the number of recalls to custody in the four years to 2017 (Independent, 17 January 2019), there is little sign of a sustained decrease in prison numbers.

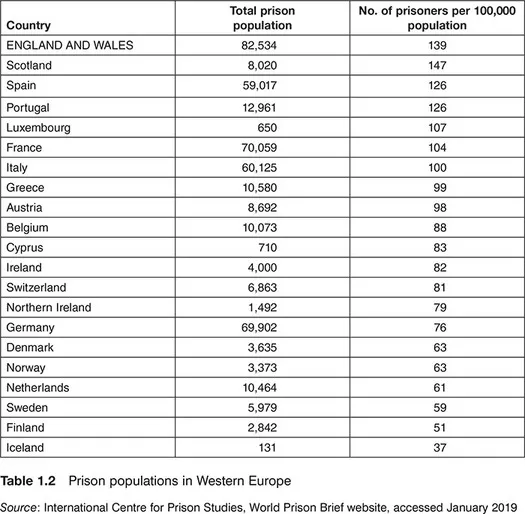

Table 1.2 Source: International Centre for Prison Studies, World Prison Brief website, accessed January 2019

As Table 1.2 shows, England and Wales (along with Scotland) currently have the largest prison population in Western Europe in proportion to the total number of people in the country as a whole.2 It is true that proportionate prison populations are even higher in some countries outside Western Europe: indeed, the United States has around five times as many prisoners relative to its population as do England and Wales.3 Nevertheless, within the Western European frame of reference Great Britain does seem to be strikingly punitive, having maintained a position high in the prison population league table for many years now. This relatively high prison population does not seem to be because the UK has more crime, or more serious crime, than comparable countries.4 Rather, it is because more offenders are sent to custody, and for longer periods, in the UK than elsewhere in Western Europe (see, for example, Barclay and Tavares, 2000; NACRO, 1998; Pease, 1992).

There should be little doubt, then, that the present and predicted future size of the prison population is a major problem. If drastic steps are not taken to reduce prison numbers – and there is currently no sign of any such steps being taken – they seem likely to grow even more alarmingly in the coming years.

Overcrowding

At the end of January 2019 English and Welsh prisons officially had adequate space for 74,571 inmates, but actually contained 82,233, making the system as a whole overcrowded by a factor of 9 per cent. By ‘adequate space’ we mean the official figure for the ‘in use certified normal accommodation’ (or ‘uncrowded capacity’5) of all prisons in total. The Prison Service also identifies a higher figure, the ‘operational capacity’, defined as ‘the total number of prisoners that an establishment can hold taking into account control, security and the proper operation of the planned regime’. Adding the operational capacity of all prisons together and deducting a safety margin of 2,000 yields a total ‘useable operational capacity’ – informally known as the ‘bust limit’ – for the system as a whole. This ‘bust limit’ was actually exceeded in April 2004 and again in February 2008. In recent years the prison population has spent many months hovering close to the bust limit, often with just a few hundred places to spare.

Even these overall figures do not do justice to the overcrowding problem because prisoners are not spread evenly throughout the system. High-security prisons (see Chapter 6, section 6.3) are frequently not filled to capacity, while overcrowding is concentrated in local prisons (which predominantly house remand prisoners and those on short-term sentences); male local prisons had a crowding rate in 2018 of 48.5 per cent (Ministry of Justice, 2018b: Table 2.5). At the end of January 2019, 58 per cent of prisons were overcrowded, with several of th...