eBook - ePub

Fundamental of Operative Dentistry

A Contemporary Approach, Fourth Edition

Thomas J. Hilton, James B. Summitt, James Broome, Jack L. Ferracane

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 612 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Fundamental of Operative Dentistry

A Contemporary Approach, Fourth Edition

Thomas J. Hilton, James B. Summitt, James Broome, Jack L. Ferracane

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Over the past two decades, Fundamentals of Operative Dentistry has become one of the most trusted textbooks on clinical restorative dentistry. By integrating time-tested methods with recent scientific innovation, the authors promote sound concepts for predictable conservative techniques. Now in its fourth edition, this classic text has been completely updated with full-color illustrations throughout and substantial revisions in every chapter to incorporate the latest scientific developments and current research findings. In addition, new chapters on color study and shade matching address new areas of focus in the preclinical curriculum. A valuable resource for understanding the scientific basis for current treatment options in dentistry.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Fundamental of Operative Dentistry est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Fundamental of Operative Dentistry par Thomas J. Hilton, James B. Summitt, James Broome, Jack L. Ferracane en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Medicina et Odontología. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Biologic Considerations

Terry J. Fruits

Sharukh S. Khajotia

Jerry W. Nicholson

Sharukh S. Khajotia

Jerry W. Nicholson

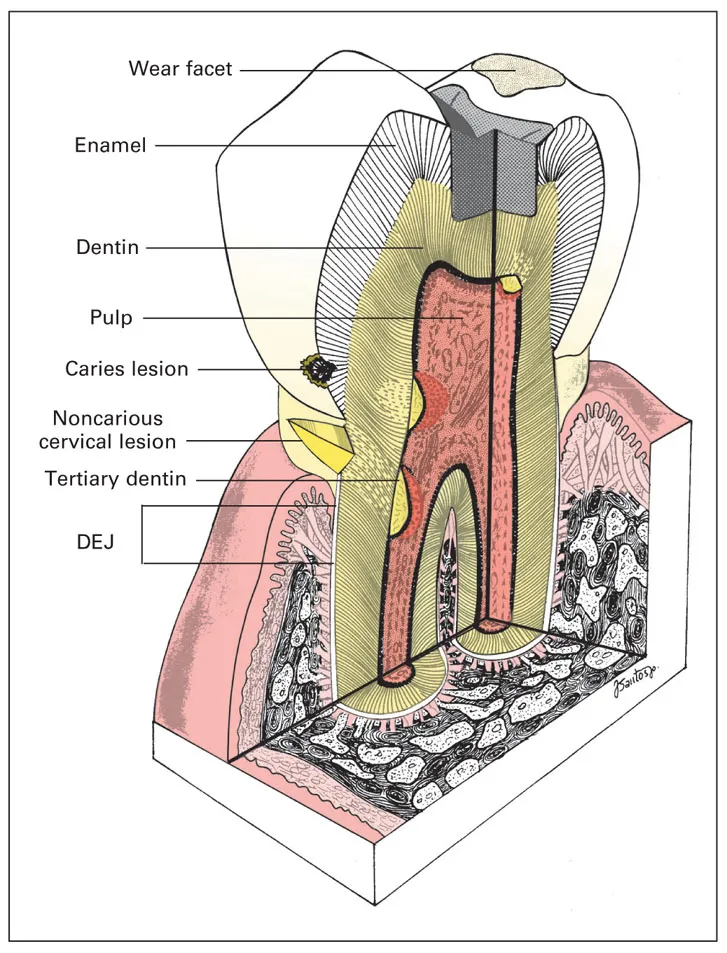

Success in clinical dentistry requires a thorough understanding of the anatomical and biologic nature of the tooth, with its components of enamel, dentin, pulp, and cementum, as well as the supporting tissues of bone and gingiva (Fig 1-1; see also Fig 1-9a). Dentistry that violates the physical, chemical, and biologic parameters of tooth tissues can lead to premature restoration failure, compromised coronal integrity, recurrent caries, patient discomfort, or even pulpal necrosis.

Fig 1-1 Component tissues and supporting structures of the tooth. DEJ—dentinoenamel junction.

The principles, materials, and techniques that constitute operative dentistry are effective only when utilized within a framework based on these biologic parameters. This chapter presents a morphologic and histologic review of tooth tissues with emphasis on their clinical significance for the practice of restorative dentistry.

Enamel

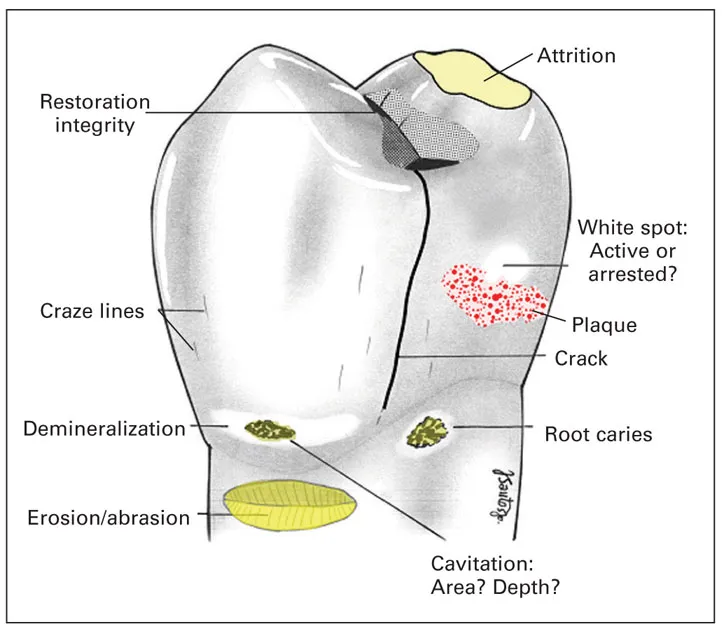

Enamel provides the shape and hard, durable outer surface of teeth, which protects the underlying dentin and pulp (see Fig 1-9a). Both color and form contribute to the esthetic appearance of enamel. Much of the art of restorative dentistry comes from efforts to simulate the color, texture, translucency, and contours of enamel with synthetic dental materials, such as resin composite or porcelain. Nevertheless, the lifelong preservation of the patient’s own enamel is one of the defining goals of the discipline of operative dentistry. Although enamel is capable of lifelong service, its crystalline mineral makeup and rigidity, exposed to an oral environment of occlusal, chemical, and bacterial challenges, make it vulnerable to acid demineralization, attrition (wear), and fracture (Fig 1-2). Mature enamel is unique compared with other tissues because, besides alterations in its mineral content, repair or replacement can only be accomplished through dental therapy.

Fig 1-2 Observations of clinical importance on the tooth surface.

Permeability

At maturity, enamel is 96% inorganic hydroxyapatite mineral by weight and more than 86% hydroxyapatite mineral by volume. Enamel also contains a small volume of organic matrix, as well as 4% to 12% by volume water, which is contained in the intercrystalline spaces and in a network of micropores opening to the external surface.1 These microchannels form a dynamic connection between the oral cavity and the pulpal interstitial space and dentinal tubule fluids.2 Various fluids, ions, and low–molecular weight substances, whether deleterious, physiologic, or therapeutic, can diffuse through the semipermeable enamel. Therefore, the dynamics of acid demineralization, reprecipitation or remineralization, fluoride uptake, and vital bleaching therapy are not limited to the surface but are active in three dimensions.3–6 When teeth become dehydrated, as from nocturnal mouth breathing or rubber dam isolation for dental treatment, the empty micropores make the enamel appear chalky and lighter in color (Fig 1-3). The condition is reversible with return to the “wet” oral environment. There is some evidence that the permeability of the enamel decreases with age and may be affected by various dental procedures, such as tooth whitening, acid etching, or the physical removal of the outermost layer of enamel.7–9

Fig 1-3 Color change resulting from dehydration. The right central incisor was isolated by rubber dam for approximately 5 minutes. Shade matching of restorative materials should be determined with full-spectrum lighting before isolation.

Lifelong exposure of semipermeable enamel to the ingress of elements from the oral environment into the mineral structure of the tooth results in coloration intensity and resistance to demineralization. The yellowing of older teeth may be attributed to thinning or increased translucency of enamel, accumulation of trace elements in the enamel structure, and perhaps the sclerosis of mature dentin. This yellowing may be treated conservatively with at-home or in-office bleaching. The enamel remineralization process benefits from the incorporation of fluoride from water sources or toothpaste and from the fluoride concentrated in the biofilm (plaque) that adheres to enamel surfaces. Enamel damaged by acid-producing biofilm bacteria can be repaired by remineralization with fluoride, which increases the rate of conversion of hydroxyapatite into more stable and less acid-soluble crystals of fluorohydroxyapatite or fluoroapatite.10 There has been a considerable amount of research recently directed at further enhancing the effectiveness of fluoride remineralization by creating new delivery systems that increase the available calcium and phosphate required to form fluoro-hydroxyapatite and fluoroapatite.11 With aging, color (hue) is intensified, but acid solubility of enamel, pore volume, water content, and permeability are reduced, although a basic level of permeability is maintained.12

Clinical appearance and defects

The dentist must pay close attention to the surface characteristics of enamel for evidence of pathologic or traumatic conditions. Key diagnostic signs include color changes associated with demineralization, cavitation, excessive wear, morphologic faults or fissures, and cracks (see Fig 1-2).

Color

Enamel translucency is directly related to the degree of mineralization, and its color is primarily a function of its thickness and the color of the underlying dentin. From approximately 2.5 mm at cusp tips and 2.0 mm at incisal edges, enamel thickness decreases significantly below deep occlusal fissures and tapers to become very thin in the cervical area near the cementoenamel junction (CEJ). Therefore, the young anterior tooth has a translucent gray or slightly bluish hue near the incisal edge. A more chromatic yellow-orange shade predominates cervically, where dentin shows through thinner enamel. Coincidentally, in about 10% of teeth, a gap between enamel and cementum in the cervical area leaves vital, potentially sensitive dentin completely exposed.13

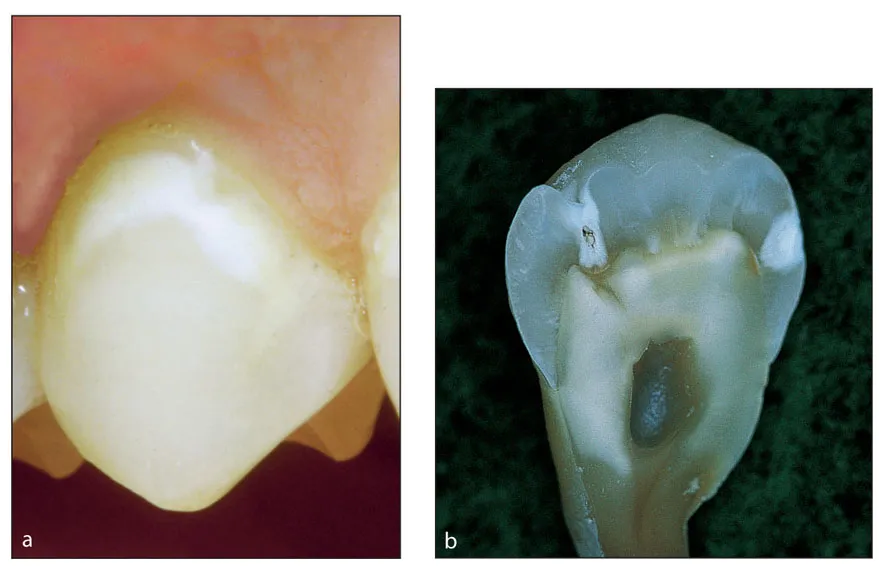

Anomalies of development and mineralization, extrinsic stains, antibiotic therapy, and excessive fluoride can alter the natural color of the teeth.14 However, because caries is the primary disease threat to the dentition, enamel discoloration related to demineralization caused by acid from a few microorganisms, primarily mutans streptococci, within biofilm15 is a critical diagnostic observation. Subsurface enamel porosity from demineralization is manifested clinically as a milky white opacity termed a white spot lesion (Figs 1-2 and 1-4). Early enamel fissure–caries lesions are difficult to detect on bitewing radiographs. However, diagnostic accuracy can be improved by a systematic visual ranking of the enamel discoloration adjacent to pits and fissures, which in turn is correlated with the histologic depth of demineralization.16,17 In the later stages of enamel demineralization extending to near the dentinoenamel junction (DEJ), the white-spot opacity is evident not only when the tooth is air dried but also when it is wet with saliva.18 It may take 4 to 5 years for demineralization to progress through the enamel,19 but with improved plaque removal and remineralization, the lesion may arrest and, with time, appear normal again. In one study, 182 white spot lesions in 8-year-old children were reevaluated at age 15 years: 9% had cavitated, 26% appeared unchanged, and 51% appeared clinically sound.20 In addition, sealing an initial caries lesion with resin has also been shown to be an effective method for arresting its further development.21,22

Fig 1-4 (a) White spot lesion on the facial surface of the maxillary premolar. (b) Premolar with both an occlusal fissure-caries lesion (Class 1), extending into the dentin, and a proximal smooth-surface caries lesion (Class 2).

A longstanding chalky and roughened white-spot appearance of the facial or lingual enamel surface (see Fig 1-4a) may be a result of factors such as inadequate oral hygiene, a cariogenic diet, and an insufficient amount of saliva resulting from medical conditions or medication. All of these factors place the patient at a higher risk for caries.23 As the caries progresses, the overlying enamel takes on a blue or gray tint that provides a clinical sign indicating advanced dentin involvement. With the adve...