eBook - ePub

Studies in the Making of Islamic Science: Knowledge in Motion

Volume 4

Muzaffar Iqbal, Muzaffar Iqbal

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 576 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Studies in the Making of Islamic Science: Knowledge in Motion

Volume 4

Muzaffar Iqbal, Muzaffar Iqbal

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Situated between the Greek, Indian and Persian scientific traditions and modern science, the Islamic scientific tradition received, enriched, transformed and then bequeathed scientific knowledge to Europe. The articles selected for this volume explore the fascinating process of knowledge in motion between different civilizations.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Studies in the Making of Islamic Science: Knowledge in Motion est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Studies in the Making of Islamic Science: Knowledge in Motion par Muzaffar Iqbal, Muzaffar Iqbal en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Social Sciences et Islamic Studies. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Part I

Greek into Arabic

[1]

THE TRANSMISSION OF HINDU-ARABIC NUMERALS RECONSIDERED

For the last two hundred years the history of the so-called Hindu-Arabic numerals has been the object of endless discussions and theories, from Michel Chasles and Alexander von Humboldt to Richard Lemay in our times. But I shall not here review and discuss all those theories. Moreover I shall discuss several items connected with the problem and present documentary evidence that sheds light—or raises more questions—on the matter.

At the outset I confess that I believe the general tradition, which has it that the nine numerals used in decimal position and using zero for an empty position were received by the Arabs from India. All the oriental testimonies speak in favor of this line of transmission, beginning from Severus Sebokht in 6621 through the Arabic-Islamic arithmeticians themselves and to Muslim historians and other writers. I do not touch here the problem whether the Indian system itself was influenced, or instigated, by earlier Greek material; at least, this seems improbable in view of what we know about Greek number notation.

The time of the first Arabic contact with the Hindu numerical system cannot safely be fixed. For Sēbōkht (who is known to have translated portions of Aristotle’s Organon from Persian) Fuat Sezgin2 assumes possible Persian mediation. The same may hold for the Arabs, in the eighth century. Another possibility is the Indian embassy to the caliph’s court in the early 770s, which supposedly brought along an Indian astronomical work, which was soon translated into Arabic. Such Indian astronomical handbooks usually contain chapters on calculation3 (for the practical use of the parameters contained in the accompanying astronomical tables), which may have conveyed to the Arabs the Indian system. In the following there developed a genre of Arabic writings on Hindu reckoning (fi l-ḥisāb al-hindī, in Latin de numero Indorum), which propagated the new system and the operations to be made with it. The oldest known text of this kind is the book of al-Khwārizmī (about 820, i.e., around fifty years or more after the first contact), whose Arabic text seems to be lost, but which can very well be reconstructed from the surviving Latin adaptations of a Latin translation made in Spain in the twelfth century. Similar texts by al-Uqlīdisī (written in 952/3), Kūshyār ibn Labbān (2nd half of the 10thcentury) and ʿAbd al-Qāhir al-Baghdādī (died 1037) have survived and have been edited.4 All these writings follow the same pattern: they start with a description of the nine Hindu numerals (called aḥruf plural of ḥarf Latin litterae), of their forms (of which it is often said that some of them may be written differently), and of zero. Then follow the chapters on the various operations. Beside these many more writings of the same kind were produced,5 and in later centuries this tradition was amply continued, both in the Arabic East and West. All these writings trace the system back to the Indians.

The knowledge of the new system of notation and calculation spread beyond the circles of the professional mathematicians. The historian al-Yaʿqūbī describes it in his Tārīkh (written 889)—he also mentions zero, ṣifr, as a small circle (dāʾira ṣaghīra).6 This was repeated, in short form, by al-Masʿūdī in his Murūj?.7 In the following century the encyclopaedist Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Khwārizmī gave a description of it in his Māfatīḥ al-ʿulūm (around 980); also he knows the signs for zero (aṣfār, plural) in the form of small circles (dawāʾir ṣighār).8 That the meaning of ṣifr is really “empty, void” has been nicely proved by August Fischer,9 who presents a number of verses from old Arabic poetry, where the word occurs in this sense. It may thus be regarded as beyond doubt that ṣifr, in arithmetic, indeed renders the Indian śūnya, indicating a decimal place void of any of the nine numerals. Exceptional is the case of the Fihrist of Ibn al-Nadīm (around 987, that is, contemporaneous with the encyclopaedist al-Khwārizmī). This otherwise well-informed author apparently did not recognize the true character of the nine signs as numerals; he treats them as if they were letters of the Indian alphabet.10 He juxtaposes the nine signs to the nine first letters of the Arabic abjad series and says that, if one dot is placed under each of the nine signs, this corresponds to the following (abjad) letters yāʾ to ṣād, and with two dots underneath to the remaining (abjad) letters qāf to ẓāʾ (with some defect in the manuscript transmission). This sounds as if he understood the nine signs and their amplification with the dots as letters of the Indian alphabet. Even a Koranic scholar, Abū ʿAmr ʿUthmān al-Dānī (in Muslim Spain, died 1053), knows the zero, ṣifr, and compares it to the common Arabic orthographic element sukūn.11 (For all these authors it must be kept in mind that the manuscripts in which we have received their texts date from more recent times and therefore may not reproduce the forms of the figures in the original shape once known and written down by the authors.)

Of some interest in this connection are, further, two quotations recorded by Charles Pellat: the polymath al-Jāḥiẓ (died 868) in his Kitāb al-muʿallimīn advised schoolmasters to teach finger reckoning (ḥisāb al-ʿaqd) instead of ḥisāb al-hind, a method needing “neither spoken word nor writing”; and the historian and literate Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyā al-Ṣūlī (died 946) wrote in his Adab al-kuttāb: “The scribes in the administration refrain, however, from using these [Indian] numerals because they require the use of materials [writing-tablets or paper?] and they think that a system which calls for no materials and which a man can use without any instrument apart from one of his limbs is more appropriate in ensuring secrecy and more in keeping with their dignity; this system is computation with the joints (ʿaqd or ʿuqad) and tips of the fingers (banān), to which they restrict themselves.”12

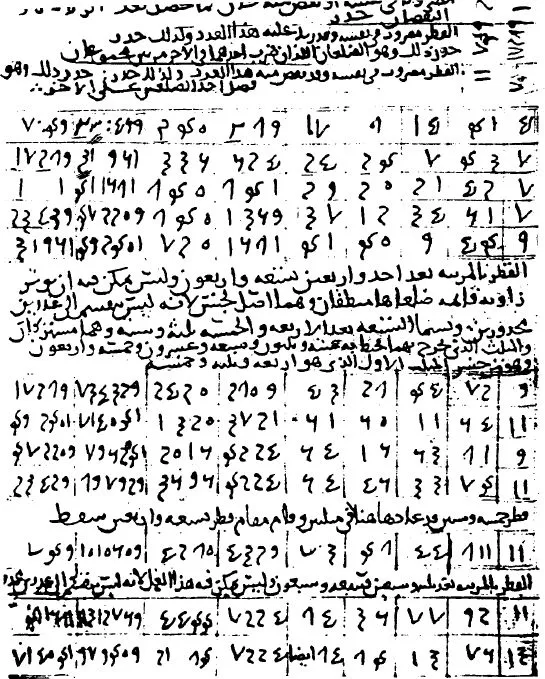

The oldest specimens of written numerals in the Arabic East known to me are the year number 260 Hijra (873/4) in an Egyptian papyrus and the numerals in MS Paris, BNF ar. 2457, written by the mathematician and astronomer al-Sijzī in Shīrāz between 969 and 972. The number in the papyrus (figure l.l)13 may indicate the year, but this is not absolutely certain.14 For an example of the numerals in the Sijzī manuscript, see figure 1.2. It is to be noted that here “2” appears in three different forms, one form as common and used in the Arabic East until today, another form resembling the “2” in some Latin manuscripts of the 12th century, and a form apparently simplified from the latter; also “3” appears in two different forms, one form as common in the East and used in that shape until today, and another form again resembling the “3” in some Latin manuscripts of the 12th century.

Figure 1.1

Papyrus PERF 789.

Reproduced from Grohmann, Pl. LXV, 12

Reproduced from Grohmann, Pl. LXV, 12

Figure 1.2

MS Paris, B. N. ar 2457, fol 85v. Copied by al-Sijzī, Shīrāz, 969–972

This leads to the question of the shape of the nine numerals. Still after the year 1000 al-Bīrūnī reports that the numerals used in India had a variety of shapes and that the Arabs chose among them what appeared to them most useful.15 And al-Nasawī (early eleventh century) in his al-Muqniʿfī l-ḥisāb al-hindī writes at the beginning, when describing the forms of the nine signs, “Les personnes qui se sont occupées de la science du calcul n’ont pas été d’accord sur une partie des formes de ces neuf signes; mais la plupart d’entre elles sont convenues de les former comme il suit”16 (then follow the common Eastern Arabic forms of the numerals).

Among the early arithmetical writings that are edited al-Baghdādī mentions that for 2,3, and 8 the Iraqis would use different forms.17 This seems to be corroborated by the situation in the Sijzī manuscript. Further, the Latin adaptation of al-Khwārizmī’s book says that 5, 6, 7, and 8 may be written differently. If this sentence belongs to al-Khwārizmī’s original text, that would be astonishing. Rather one would be inclined to assume that this is a later addition made either by Spanish-Muslim redactors of the Arabic text or by the Latin translator or one of the adapters of the Latin translation, because it is in these four signs (or rather, in three of them) that the Western Arabic numerals differ from the Eastern Arabic ones.18

Another point of interest connected with Hindu reckoning and the use of the nine symbols is: how these were used and in what form the operations were made. Here the problem of the calculation board is addressed. It was especially Solomon Gandz who studied this problem in great detail and who arrived at the result that the Arabs knew the abacus and that the term ghubār commonly used in Western Arabic writings on arithmetic renders the Latin abacus.19 As evidence for his theory he also cites from Ibn al-Nadīm’s Fihrist several Eastern Arabic book titles such as Kitāb al-ḥisāb al-hindī bi-l-takht (to which is sometimes added wa-bi-l-mīl ), “Book on Hindu Reckoning with the Board (and the Stylus).” I cannot follow Gandz in his argumentation. It is clear, on the one side, that all the aforementioned eastern texts on arithmetic, from al-Khwārizmī through al-Baghdādī, mention the takht (in Latin: tabula) and that on it numbers were written and—in the course of the operations—were erased (mahw, Latin: delere). It seems that this board was covered with dust (ghubār, turāb) and that marks were made on it with a stylus (mīl). But can this sort of board, the takht (later also lawḥ, Latin tabula), be compared with the abacus known and used in Christian Spain in the late tenth to the twelfth centuries? In my opinion, definitely not. The abacus was a board on which a system of vertical lines defined the decimal places and on which calculations were made by placing counters in the columns required, counters that were inscribed with caracteres, that is, the nine numerals (in the Western Arabic style) indicating the number value. The action of maḥw, delere, erasing, cannot be connected with the technique of handling the counters. On the other side, the use of the takht is unequivocally connected with writing down (and in case of need, erasing) the numerals; the takht had no decimal divisions like the abacus, it was a board (covered with fine dust) on which numbers could be freely put down (Ibn al-Yasamln speaks of naqasha) and eventually erased (maḥw, delere). Thus it appears that the Arabic takht and the operations on it are quite different from the Latin abacus. Apart fro...