![]()

Chapter 1

Sustainability drivers

In which we present some of the history of ideas that have brought about a shared understanding of the benefits of implementing checks and balances in pursuit of genuine and sustainable progress for everyone, now and in the future.

Carved door

There is lots of evidence that the environment is deep rooted in human consciousness.

Photo: The Author

“The choice is simple, sustainable development, unsustainable development, or no development at all.”

Sandy Halliday, Build Green (1990)

The Andersen House, Stavanger, 1984

The first modern building designed to be moisture transfusive. Student architects and builders: Dag Roalkvam and Rolf Jacobsen; Photo: Dag Roalkvam

Contents

Introduction

Development

History of international action

The Club of Rome, 1968

Limits to Growth, 1972

A systems approach

UNCHE, 1972

Optimism versus pessimism

Oversimplification versus synergies

A note on inertia

WCED –The Brundtland Commission, 1981

The Brundtland Report, 1987

UNCED, 1992

UNFCCC, 1992

The Millennium Summit, 2000

WSSD, 2002

Rio+20 Conference, 2012

Sustainable Development Summit, 2015

UN High Level Political Forum, 2017

Recent progress?

Bibliography

Case studies

1.1 Solar Hemicycle, Wisconsin, USA

1.2 St George’s School, Wallasey, England

1.3 Arcosanti, Arizona, USA

1.4 Street Farm House, London, England

1.5 Walter Segal Self-build Housing, London, England

1.6 The Ark, Prince Edward Island, Canada

1.7 Granada House, Macclesfield, England

1.8 Andersen House, Stavanger, Norway

1.9 Rocky Mountain Institute, Colorado, USA

1.10 NMB Bank, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Introduction

There can be few within the professions involved in the built environment for whom sustainability is a new idea. Local, national and international policies, professional guidelines, client briefs and architectural competitions mean that it is a subject rarely out of the press. Yet, for an issue this ubiquitous, it is poorly understood, and a source of much debate and disagreement.

It is not wholly surprising that the concept is difficult to communicate. Sustainability involves big issues and their complex interaction: the division of wealth and opportunity between the world’s rich and poor, health, welfare, safety, security and useful work as basic needs of societies, and rights of individuals. Much is predicated on the rights of the young, the unborn, those in society least capable of looking after themselves and other species, a concept unimaginable a few generations ago.

In essence, sustainability is about how we develop. The state of the environment is a fundamental aspect because the consequences of our activities impact directly on our current and future quality of life, impose burdens on others, and threaten other species.

The global, social and cultural issues with which sustainability is concerned can be difficult to translate into the practicalities of what building design and cost professionals do on a daily basis. Appropriate and meaningful responses are genuinely hard to identify and we still know little about what responses are adequate to combat the risks.

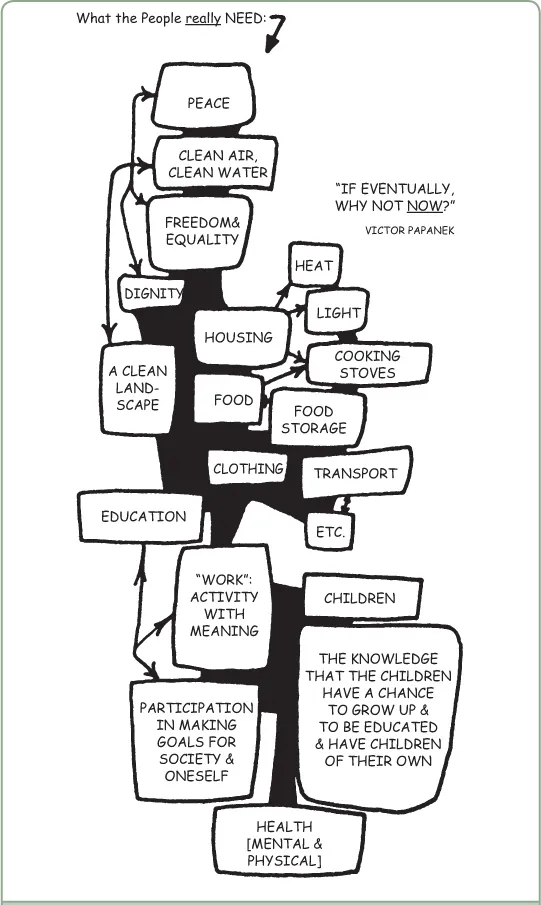

What people really need

After Papanek, Design for the Real World 1971

Human failure to appreciate our dependence on the natural world, and to plan and design accordingly, is widely evident. Many developing countries have adopted styles and scales of development established by richer countries, including building forms and transport that are now widely acknowledged as inappropriate and unsustainable. Younger generations across the globe are adopting unsustainable lifestyle choices with adverse local and international effects. With evidence of massive environmental damage, it may seem pointless to try to do anything about it unless we appreciate that sustainable design is about delivering real benefits.

Alongside the environmental destruction in developing countries there are exemplar ecological cities and towns developing in South America, Taiwan, India and the USA. Their ambitions and success or failure will determine life quality for the majority in this millennium. Global movements like Eco-minimalism (Liddell 2008) also challenge us to think about what is appropriate and fulfilling development. Engaging young people in the issues and communicating the benefits to a global generation is invaluable work.

This chapter puts forward something of the history of ideas about sustainable development and readers can make their own judgements about what response is required and possible. The case studies illustrate some early initiatives and exploration in living within environmental boundaries while delivering socially beneficial outcomes. Many of the principles that they embody are vital precedents for technical and societal improvements, and have been developed by subsequent cohorts of ecological and sustainable designers. They are not the only precedents, but they have left a lasting impression.

Development

‘Sustainable development’ has suffered from an image problem. It requires us to act in an overtly sensitive manner towards natural systems and has been seen by those who would do otherwise as a restraint on ‘development’ per se. As policies and practice have matured, sustainable development is increasingly recognised as a justified restraint on ‘inappropriate’ development and a driver of improving quality of life for all. It is increasingly attractive to many to put in place long-term policies that can reliably deliver social, environmental and economic improvements, especially against a background of increasing demand on the Earth’s limited resources and escalating pollution.

Human skills have transformed the environment. For the developed world and many in the developing world, access to sanitation, vaccination, health awareness and treatment, food hygiene and good diet has vastly extended the quality and quantity of life in recent decades. However, the extent to which our activities are unsustainable has become clearer over the same period. There has been an increasing realisation that changes in the pursuit of progress are often accompanied by unintended consequences that need to be recognised and avoided.

New Superstore – Derelict high street

Achieving sustainable development requires us to process the consequences of decisions and resist inappropriate development.

There is now overwhelming acceptance that we face major global problems of climate change, ozone depletion, over-fishing, species loss, fresh water shortage, resource depletion, soil erosion, noise, deforestation, desertification, chemical and electromagnetic pollution, and congestion. Pollution of air, land, water and food threatens to crucially undermine the security, health and quality of life that humankind has pursued and sought to protect, and it threatens other species.

There is increasing wealth but also widening inequality. A significant proportion of the global population still lives with the ever-present threat of floods and/or drought, pestilence and starvation, often exacerbated by wars. Many are subject to scarcity, poor hygiene and unsanitary conditions, often within close proximity of abundance. There is growing awareness of moral responsibility favouring greater equity, and evidence to suggest that those countries with the widest wealth gaps also suffer the greatest incidence of crime and ill-health (Pickett & Wilkinson 2010).

Humankind faces an awesome challenge to reverse unsustainable trends. With rising expectation and consumerism, questions must at some time surface. Can we maintain and improve life quality while radically improving the effectiveness in how we use our resources, and reduce pollution and waste? Evidence suggests we c...