eBook - ePub

Essentials of Logic

Irving Copi, Carl Cohen, Daniel Flage

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 463 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Essentials of Logic

Irving Copi, Carl Cohen, Daniel Flage

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Rendered from the 11th Edition of Copi/Cohen, Introduction to Logic, the most respected introductory logic book on the market, this concise version presents a simplified yet rigorous introduction to the study of logic. It covers all major topics and approaches, using a three-part organization that outlines specific topics under logic and language, deduction, and induction. For individuals intrigued by the formal study of logic.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Essentials of Logic est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Essentials of Logic par Irving Copi, Carl Cohen, Daniel Flage en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Philosophy et Philosophy History & Theory. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

CHAPTER ONE

BASIC LOGICAL CONCEPTS

1.1 WHAT LOGIC IS

Logic is the study of the quality of arguments. Broadly speaking, an argument is an attempt to provide reasons for accepting the truth of some claim. (We give a more precise definition of argument in section 1.3.) Some arguments provide good reasons; other arguments do not. This book teaches you how to identify and evaluate arguments so that you will be able to sort good arguments from bad ones. Logic is a kind of self-defense. Understanding logic helps you to avoid being fooled. It encourages you to seek good reasons for your beliefs. Understanding logic also enables you to construct better arguments of your own. Arguments help us to determine whether or not to believe what we read in the newspaper or see on television. They help us reach decisions. They are the backbone of the essays that we read and write. We even use arguments when talking with friends. The skills taught in this logic book are useful in everyday life.

1.2 PROPOSITIONS AND SENTENCES

All arguments are constructed out of propositions or statements, so we begin by discussing them. A proposition is something that can be asserted or denied. A proposition is either true or false. It is true if it corresponds with the facts it describes. If it does not correspond, it is false. In this way propositions differ from questions, requests, commands, and exclamations, none of which can be asserted or denied. Although a defining feature of propositions is that they are either true or false, we may not always know whether a given proposition is true or false.

Example

The proposition “David Letterman sneezed three times on his twentyfirst birthday” is either true or false, but we will probably never know which one it is.

Questions, commands, requests, and exclamations do not make claims about the world. Unlike propositions, they do not have truth values; they are neither true nor false.

Declarative sentences are used to communicate propositions in print or speech. Sentences are not propositions. A proposition is what is meant by a declarative sentence in a certain context. Two sentences can state the same proposition. Propositions are independent of the language in which they are stated. For example, “Il pleut,” “Es regnet,” and “Está lloviendo,” are different sentences that assert the same proposition: They assert that it is raining. And, of course, there are many ways to assert the same proposition in a given language.

Example

A. George W. Bush won the 2004 U.S. presidential election.

B. The winner of the U.S. presidential election held in the year 2004 was George W. Bush.

C. George W. Bush was elected to the U.S. presidency in 2004.

These sentences differ in structure. However, they have the same meaning; they are true under the same conditions. All three sentences assert the same proposition.

Notice, too that the same sentence can be used in different contexts to assert different propositions. The time and place at which a sentence is uttered may affect the proposition it asserts.

Example

Humans have walked on the moon.

If this statement had been uttered before 1969, it would have been false. If uttered after 1969, it is true.

It is raining.

If it is raining at the place and time this sentence is uttered, it is true. At other places and times, it is false.

You are a thief!

At one time and place, this sentence might assert (truly or falsely, depending on the facts) that Bob is a thief, while at another time, it might assert (truly or falsely) that Joan is a thief.

ESSENTIAL HINTS

Logicians distinguish between propositions, statements, and sentences. A proposition is what is asserted. A statement is the proposition asserted by a sentence in a particular language. The meanings of proposition and statement are close enough to one another that we shall use them interchangeably.

In later chapters, we discuss properties of propositions. Some propositions have other propositions as parts (they are compound propositions). Others don’t (they are simple propositions). Sometimes the structures of propositions make important differences in the arguments in which they are found.

1.3 ARGUMENTS, PREMISES, AND CONCLUSIONS

An inference is a mental process by which one proposition is arrived at and affirmed on the basis of one or more other propositions that are assumed as the starting point of the process. To determine whether an inference is correct, the logician examines the propositions with which that process begins and ends and the relations among them. This cluster of propositions constitutes an argument.

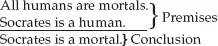

Now we are ready to formulate a more precise definition of argument. An argument is a collection of propositions in which some propositions, the premises, are given as reasons for accepting the truth of another proposition, the conclusion. In the following argument:

the first two propositions are the premises. They provide reasons to believe that the conclusion, “Socrates is a mortal,” is true.

In ordinary discourse we use the word argument in other ways. For example, someone might say, “My parents divorced because they were always arguing.” But in logic we restrict the term argument to refer only to attempts to provide premises in support of conclusions. Arguments do not require disagreements.

An argument is not merely a collection of propositions. The propositions have to have a certain kind of relationship in order to be an argument. The premises of an argument must provide reasons to believe (evidence) that the conclusion is true. In practice, the premises of an argument are known or assumed before the conclusion is known.

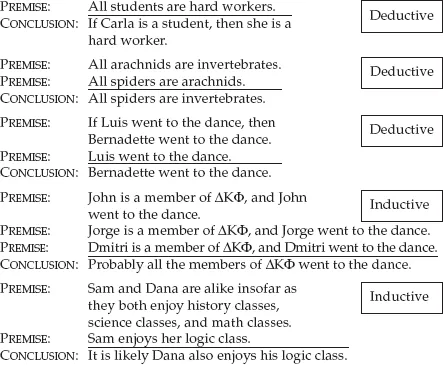

There are two basic types of arguments. A deductive argument is an argument that attempts to prove the truth of its conclusion with certainty. This book concentrates mainly on the logic of deductive arguments. An inductive argument is one that attempts to establish its conclusion with some degree of probability. There are many kinds of deductive and inductive arguments, but the general descriptions just given always apply. Section 1.8 of this chapter gives you more information about induction, and the final chapter of the text examines some common inductive argument types in detail. Inductive and deductive arguments are evaluated according to very different standards.

Before we get to the standards for evaluating specific types of arguments, let’s continue with the general account of arguments. An argument always has at least one premise. There is no upper limit to the number of premises, but two or three is common. Additionally, there is always exactly one conclusion per argument. No single proposition by itself constitutes an argument. Here are some examples of arguments:

These five sample arguments are all arranged in standard form. In standard form, the premises are stated first and the conclusion last, with a single proposition written on each line, and a line is drawn between the premises and the conclusion. By stating arguments in standard form, you show the relationship between the premise(s) and the conclusion. But in ordinary written and verbal communication, arguments are often not stated in standard form. For example, it is very common for the conclusion of an argument to be stated first and the premises given afterwards:

The Food and Drug Administration should stop all cigarette sales immediately. After all, cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable death.

In this case, the first sentence is the conclusion, and the second sentence is the reason that we are supposed to accept the truth of the claim made by the first sentence.

The techniques logicians have developed for evaluating arguments require that one distinguishes between the premise(s) and conclusion of an argument. If you ...