![]()

1

Political turmoil and ‘Libyan’ settlers: setting the scene

Histories of eras before the Saite Dynasty (26th Dynasty) in ancient Egypt have been largely based on Egyptian evidence, in spite of its inherent distortions and biases, as this has been the only major source available. With the Saite Period there is for the first time a much broader range of archaeological and written evidence from outside the borders of the country as well as the traditional Egyptian sources. The Assyrian prisms, Babylonian and Persian sources and the accounts of the Classical authors allow cross-referencing and contribute to our understanding of this era. Particularly notable are the narratives of Herodotus which are still an important source on Saite Egypt and have been especially dominant in establishing a history of this period in modern accounts. Although caution is required when evaluating data from Herodotus's Histories,1 there is much to be gleaned from a judicious study of his works. In addition, the dates for the 26th Dynasty are well established, tied as they are to the firm chronologies of Greece, Babylonia and Persia.

The Saite reunification of Egypt in the mid-seventh century BC appears to have brought an end to the Third Intermediate Period and the occupation of Egypt firstly by the Kushites and then later by the Assyrians. This so-called Intermediate era was a time of diminished centralised power, political fragmentation and the appearance of rulers of non-Egyptian extraction. It resulted in significant changes in society and culture and represents a distinct phase in the history of ancient Egypt. The Third Intermediate Period continued the gradual loss of political unity already apparent at the end of the New Kingdom and concluded with the restoration of centralised authority, and the reunification of Egypt by Psamtek I, usually accepted as the first ruler of the 26th Dynasty.

I Political turmoil

Monarchy and administration

The Third Intermediate Period is typically considered to commence with the death of Ramesses XI at the end of the 20th Dynasty.2 The power of Egypt and the authority of the later Ramesside rulers had been diminishing for a number of years. During the height of the New Kingdom, foreign trade, tribute and plunder had made Egypt wealthy and powerful, but the late Ramesside kings suffered a number of crises, and the history of the 20th Dynasty is one of apparent decline. Many of the factors that hastened the demise of the New Kingdom are well recognised, others less so, but a number are relevant to the revival of the power of Egypt during the Saite Period.

Ramesses III, the last significant ruler of the New Kingdom, died in the mid-twelfth century BC and was succeeded during the next century by a further eight rulers who bore Ramesses as one of their names. Little is known about some of these rulers; a number were elderly and reigned for only a short period of time, and on occasions appear to have been weak and unprepared for leadership.3 There was a diminution in royal authority and a decline in temple building programmes, and foreign activity was reduced. The lack of any significant military achievements and failure to campaign beyond the borders of Egypt would have reduced the military prestige of the monarch, an important attribute of the Pharaonic institution. The monarch increasingly relied on officials to control the provincial administration. Such a strategy resulted in a reduction in the personal influence and esteem of the king, which inevitably would have increased power in the hands of the regional administrations.

At Thebes, the authority of the priesthood of Amun and particularly the First Priest of Amun continued to increase as it had been doing throughout much of the New Kingdom. The Great Harris Papyrus dated to the reign of Ramesses III enumerates the huge donations of land-holdings that were now being made to the larger temples in Egypt, particularly the temple of Amun at Thebes.4 The god Amun was now considered to rule like a king of Egypt and, through oracles, to intervene directly in affairs of state, increasingly assuming the king's role in appointing officials. The king's role was now reduced to that of a representative of Amun and this ideology finds expression in a hymn to Amun (ll. 39–40):5

The King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Amun-Re, King of the Gods,

Lord of heaven and earth,

Of the water and the mountains,

Who created the land through his transformation.

He is greater and more sublime

Than all the gods of primordial times.

Thebes was now a theocracy and the priests were the representatives of the god. Government consisted of a regular Festival of the Divine Audience at Karnak where the god's statue communicated through oracles, with a particular motion of the barque being interpreted as acceptance or rejection of a proposal or ruling. A similar state of affairs may have occurred in Lower Egypt as implied in the story of Wenamun (mentioned below) when Smendes and his wife, Tentamun, are referred to as ‘the pillars Amun has set up for the north of his land’. Smendes is not given the title of king in this passage and may at that time have been high priest at Tanis and governor, before then later becoming ruler.6

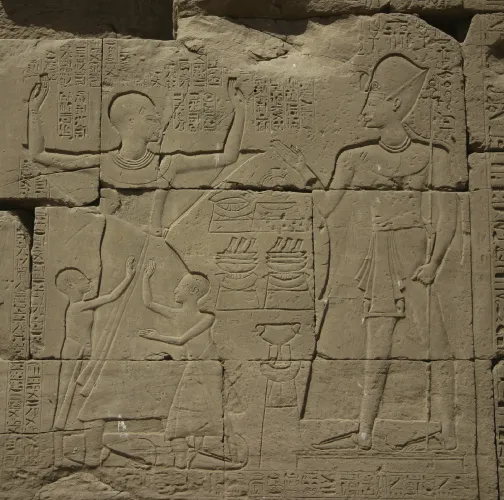

Administratively, the late New Kingdom was characterised by the political significance of hereditary office and the ability of some powerful families to control state and temple offices through intermarriage and inheritance. Throughout this period the office of High Priest at Thebes became increasingly more independent, with the monarch having only nominal control of Upper Egypt.7 In the reign of Ramesses IX, Ramesses is depicted in the form of a statue in a large relief on a temple wall opposite the sacred lake at Karnak, rewarding the High Priest Amenhotep with gifts. Amenhotep is portrayed with a stature almost equal in size to that of the king, indicating equality of status in iconographic terms (Figure 1.1).8 A far cry from the all-powerful ‘god-king’ of previous eras, when it would have been unprecedented to depict a priest at the same scale as the king, particularly in a large scene and in such a visible location.

Failing economy and loss of empire

The economy weakened during the last years of the New Kingdom and the beginning of the Third Intermediate Period. The tribute and plunder that had arrived in Egypt at the height of the New Kingdom were now a thing of the past, and foreign trade had been diminishing since the reign of Ramesses III. The revenues from the Levant and the African interior were very much reduced.

This unfavourable economic climate resulted in internal strife. In Year 29 of Ramesses III there were strikes by ...