![]()

1

Introduction: spare parts

Un pied un oeil le tout mélangé aux objets.

Fernand Léger 1

Limit-bodies: an elusive corpus

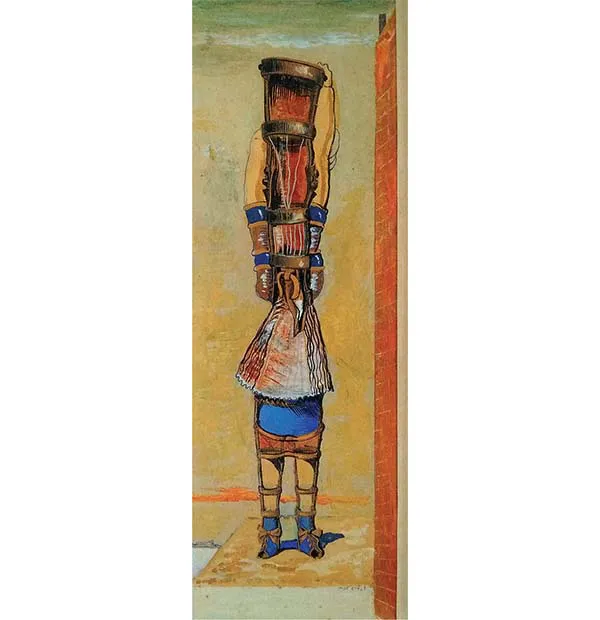

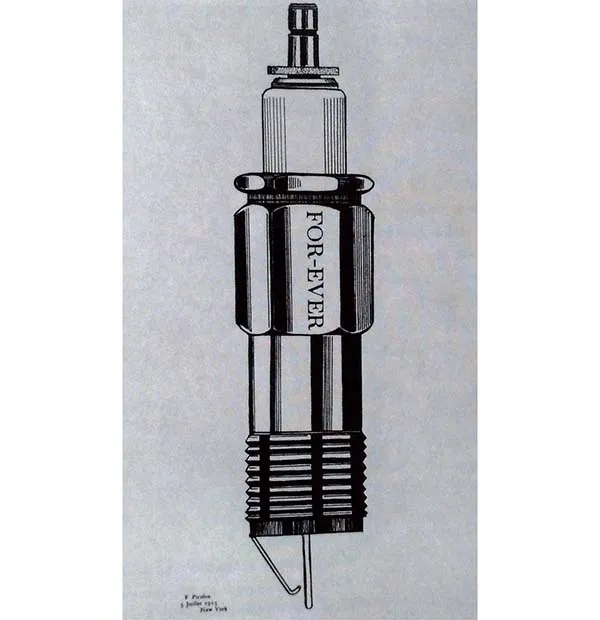

An assemblage of prosthetic limbs (figure 1.1); a spark plug with the words ‘FOREVER’ stamped on it (figure 1.2); a hybrid of African statue and European woman; a readymade object, tube or piston, eggbeater or hat; a blot, blob or blur. The Dadaists rejected mimetic representations of the human form: the body in Dada is displaced, deformed or dissolved, a mutating organic limb or an elusive limit-form of the human anatomy. In their paintings, collages and assemblages, their readymades, manifestos, poems and films, the Dadaists exposed, expelled or exploded the human figure, loudly proclaiming its demise or tentatively announcing its renewal.

Can a common denominator be found among such seemingly disparate and contradictory bodily images? In the principle of subversion of the once-whole classical body, for instance? Such an approach would risk branding Dada as a mere anti-art strategy. In the image of the fragmented body of the wounded soldiers, the shattered identities of the shell-shocked of the First World War, or the image of the machine-body of the post-war assembly lines? This would risk reducing Dada to a mirror of the reality of wartime and post-war Europe, a mere form of (second-degree) mimeticism. In the idea of a therapeutic strategy, in which collective or individual vital energies that had been constricted in the coffin-corset of the wartime years, are liberated anew in a carnivalesque space? This would be to bypass Dada’s political import or its satirical dimension. In the elaboration of a monstrous rhetoric of the body, the dissection of its parts and links? This would be to forget that Dada cannot be subjected to an overarching system; indeed, that it is an aleatory, mutable entity, often displaced, abstract or near-invisible.

1.1 Max Ernst, Jeune chimère (Young Chimera, c.1921)

Inadequate though they are as grounds for a meaningful common denominator when taken individually, each of these aspects of Dada, along with their caveats, will be shown to be relevant to the analysis of our corpus. Dada was primarily the voice of revolt and vitality, its urgency encapsulated in a woodcut by German artist Otto Dix titled Der Schrei (The Shout, 1919), and echoed in a text written by Romanian poet Tzara in 1930, which repeats the word ‘hurle’ (‘howl’) 275 times (Tzara 1975: 387).2 It was a cry of protest against a civilisation that was reducing much of Europe to rubble. In Tzara’s ‘Manifeste dada 1918’, war is seen as the manifestation of the bankruptcy of Europe’s political, social and moral values, ‘the state of madness, aggressive complete madness of a world abandoned in the hands of bandits, who rend and destroy the centuries’ (1918: 3; 1975: 366).3

Why choose to turn the spotlight on the body in Dada?4 Primarily, in response to the centrality of images of the human form in Dada, not only as a physical reality but more specifically as a social and political reality. Dada’s corporeal figurations, when considered as constructs, appear as the site of cultural mediations between the individual and the collective, as the locus of conflicts and reconfigurations, or the theatre of contradictions. Embodying Dada’s rebellion, they are a site for the philosophical, political and aesthetic questioning, erosion or subversion of social conventions, undermining dominant power relations, challenging enshrined gender differences and defying notions of fixed identities. Such images can therefore be read as tropes, essentially critical statements on the dominant ideology, exposing the dislocated body and body politic which the post-war ‘return to order’ was actively seeking to suppress or deny. Dada’s bodily images are overt fictions and fabrications which act both as a reflection of the disjunctive body of the early twentieth century, and a reflection on the dehumanised body of wartime and post-war Europe. Moreover, Dada’s strategies of perversion or subversion of the normative body transcend the simple act of resistance against social norms and initiate an exploration of new modes of individual or collective experience, offering a blueprint of the possible body.

1.2 Francis Picabia, Portrait d’une jeune fille américaine dans l’état de nudité (Portrait of a Young American Girl in a State of Nudity, 1915)

This study explores the fabrications of the human figure across Dada art, texts, film, manifestos and performances in the context of the tensions and contradictions of the ideological, socio-political and artistic situation across Europe during and after the First World War. Born in Zurich in 1916, at the heart of a war-torn Europe, Dada emerged at a time of social, economic and moral crisis, and of major developments in technology and media culture. It is this period of widespread upheaval that Walter Benjamin evokes in ‘The Storyteller’:

With the [First] World War a process began to become apparent which has not halted since then. Was it not noticeable at the end of the war that men returned from the battlefield grown silent – not richer, but poorer in communicable experience? … For never has experience been contradicted more thoroughly than strategic experience by tactical warfare, economic experience by inflation, bodily experience by mechanical warfare, moral experience by those in power. A generation that had gone to school on a horse-drawn streetcar stood under the open sky in a countryside in which nothing remained unchanged but the clouds, and beneath these clouds, in a field of forces of destructive torrents and explosions, was the tiny, fragile human body. (Benjamin 1999: 84)5

Through their literary, artistic and programmatic activities, the Dadaists both reflected and reflected on these radical changes and the ensuing turmoil. Their fabrications of the human figure have both a critical and a utopian dimension. In critical guise, they exposed the lies of an ideology that sought to clothe the corpse, to shore up the ‘tiny, fragile human body’ of war-torn Europe and to deny the disturbing presence in society of shattered bodies and minds. In this confrontation, the Dadaists staged in their texts and images the demise of the integral body of pre-war Europe, both the body politic, founded on the principle of the authoritarian state, and the aesthetic body, epitomised by the classical Greek statue. These they replaced by the dismembered, dehumanised, reconstructed or mechanised beings of a post-war Europe mired in its inability to heal physical and psychic wounds. In utopian guise, on the other hand, Dadaists disavowed traumatic memories, denying the demise of the whole body and reaffirming, on the contrary, its continuing vitality in images of the body transformed and reconfigured. It is this paradoxical aspect of Dada, as dystopian body (dysfunctional, disjunctive, dismembered) and utopian body (extended, exploded, ex-static), that this study will explore, arguing that Dada’s bodily images occupy an ambivalent space, between death and rebirth, between the battlefield (in the satirical exposure of the physical and psychic violence of the times) and the fairground (in the regression to the infantile and the celebration of the life-force).

The exploration of Dada’s bodily imagery will be taken further by considering Dada itself as corporeal, in the sense developed by Jean-Luc Nancy: ‘To write, not about the body, but the body itself. Not corporeality, but the body. Not the signs, images and figures of the body, but again the body. This was, and probably is no longer, one of modernity’s objectives’ (1992: 12).6 The notion is central to Tristan Tzara’s claim that whereas Western man has lost his sense of the tactility in favour of the head in what constitutes a form of disembodiment, Dada poetry and art are literally embedded in the body: ‘Thought is produced in the mouth’ (‘La pensée se fait dans la bouche’), he writes about Dada poetry in 1920 ([1924] 1963: 57; 1975: 379); and in 1947: ‘Thought is produced through the hand’ (‘La pensée se fait sous la main’, 1992: 368). Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes champions the same direct language–body connection when he writes in his 1920 ‘Manifeste selon Saint-Jean Clysopompe’: ‘Words come swirling out of your navel. Like a troop of archangels with candlewhite buttocks. You talk out of your navel, your eyes turned to heaven’ (1920a: 3).7

The aim of the present study is thus neither to retrieve Dada by reducing it to a homogeneous movement – anti-war, anti-logic, anti-modernity – nor to uncover a unifying principle beyond the proliferation of its spare parts. If Dada was a bomb, as Max Ernst claimed in an interview with Patrick Waldberg in 1958, why should one now wish to put the pieces back together: ‘Dada was a bomb. Can you imagine someone, almost half a century after the explosion of a bomb, intent on collecting the shards, pasting them together and displaying them?’ (1970: 411).8 Endorsing Ernst’s statement, this study investigates the make-up and impact of some of the splinters, in particular those shards which succeeded in dislocating the unified body of pre-war Europe and fabricating the anti-body, the new body or the possible body of the immediate post-war years. Hence, sidestepping any urge to recuperate Dada, it is the heterogeneity of the movement that will occupy centre stage. To this end, this study acknowledges Dada’s geographical multi-centredness and the distinctive social and political contexts which shaped the activities of its various groups. If Dada was indeed a chameleon, as Tzara proclaimed in ‘Dada est un microbe vierge’ (1920a), it changed its colours in response to its targets: ‘Dada has 391 different attitudes and colours according to the sex of the president … Dada is the chameleon of rapid and self-seeking change’ (1975: 385).9 In a similar spirit, Francis Picabia playfully assembles Dada as a multi-limbed and multinational figure in his text ‘Dada philosophique’:

DADA has blue eyes, a pale face, curly hair; he has the English look of young sportsmen.

DADA has melancholic fingers, the Spanish look.

DADA has a small nose, the Russian look.

DADA has a porcelain arse, the French look. (Picabia 1920a: 5; 1975: 225)10

The Dada movement had its origins in Zurich in neutral Switzerland, ‘a birdcage, surrounded by roaring lions’, according to Hugo Ball (1996: 34), in the revolt of a cosmopolitan group of displaced writers, artists and performers against the traditional values which had led to the catastrophe of the First World War.11 It was in Zurich on 5 February 1916 that German writer and theatre director Hugo Ball (1886–1927) opened a literary cabaret, the Cabaret Voltaire, where the first Dada activities took place. It was here that an international group of writers and artists first gathered around Ball, including Richard Huelsenbeck from Germany, Hans Arp from Alsace, Marcel Janco and Tristan Tzara from Romania.12 The movement soon spread to other European cities, including Cologne, Barcelona and Hanover.

In 1917 Huelsenbeck returned to Berlin, where he founded the Club Dada with Franz Jung and Raoul Hausmann. On 12 April 1918 Huelsenbeck declaimed the ‘Dadaistisches Manifest’, signed by Hausmann, Jung, Grosz and others. Berlin Dada culminated in the international Dada-Messe in 1920, held at Dr Otto Burchardt’s gallery (see chapter 4). The Zurich Dadaists were also in touch with a group of young French poets – André Breton, Paul Éluard and Louis Aragon – around the publication Littérature, which took on a resolutely Dada tone in 1920 when Tzara accepted Breton’s invitation to join them in Paris. Over the next two years he acted as impresario of a series of Dada soirées, but these activities were brought to an end in 1922 following a quarrel between Tzara and Breton. Dada was also active in Cologne (see chapter 7) and in New York, from 1916, where the key figures were Duchamp, Picabia and Man Ray (chapter 4).

Dada as an international movement was thus embodied in exchanges and collaborations across Europe and New York, while each Dada centre had its own distinctive character and preoccupations. Zurich, for instance, was invaded by the carnival masks of a grotesque Totentanz, while in Hanover Kurt Schwitters’s collages played nostalgically with fragments of nineteenth-century iconography. Berlin Dada proved to be a much more violently political animal, exploiting photomontage’s prosthetic bodies as a critique of Weimar Republic policies and the new media, while Cologne’s Dadaists exploited black humour and the grotesque to mock the post-war situation. And in Paris we encounter dadaist ‘exquisite corpses’, which are, arguably, more playful, more exquisite than corpse. As for New York, the human figure provided both a playful embrace and a critique of machine and commodity culture. It is in pursuing the tendency towards significant diversification that Höch’s fragmented figures, for example, will be shown to contrast with George Grosz’s bestial beings or Max Ernst’s erotic hybrids. And these, in turn, will be viewed in relation to the ironic manipulations of machine images by Francis Picabia or Marcel Duchamp. Dada’s proliferation and paradoxes, its ludic and morbid dimensions, its regressive or projective impulses thus constitute the focal points of the investigation. It will be argued that it is this very proliferation and these paradoxes which constitute the specificity – and not the (impossible) essence – of Dada as a mobi...