8.1 Matrices and Substrates

Because latent fingerprints are invisible, they must be processed, or developed, to make them visible. Once they are visualized, they are documented and analyzed. There are four major limitations that affect the quality of prints recovered from the crime scene or items of evidence:

Condition of the substrate (texture and permeability)

Environmental effects (dry, humid, rain, wind, etc.)

Quantity of latent print material deposited

Method(s) of development, documentation, and collection

Recall that latent fingerprint deposits are composed of 98% water, lipids (fatty acids, cholesterol, squalene, and triglycerides), amino acids and proteins, environmental contaminants (lotions, soaps, cosmetics, etc.), and the products of environmental chemical reactions following deposition.1–4 The majority of these components are metabolic excretory products from the pores of eccrine glands. Eccrine glands are the sweat glands most abundant along friction ridge structures. Champod et al. state, “Secretions from eccrine and apocrine glands are mixtures of inorganic salts and water-soluble organic components that result in a water-soluble deposit. Secretions from sebaceous glands consist of a semisolid mixture of fats, waxes and long-chain alcohols that result in a non-water-soluble deposit.”5 Sebaceous glands, associated with hair follicles, are most abundant on areas of the skin that perspire, especially the scalp and face.1,4 When one touches the face or scalp, the oils from these areas are transferred to the friction ridges of the fingers and palms; however, most often latent print residue is eccrine in origin.4

A latent fingerprint generally consists of both water-soluble and water-insoluble materials. After a latent is placed on a surface, it is subject to environmental effects, and its composition begins to change. The water constituent begins to evaporate when exposed to the air. A latent print can lose nearly 98% of its original weight within 72 h of deposition. Arid, hot, and windy climates can speed up this process. Conversely, a humid climate slows down the process of latent print evaporation. Other environmental effects can be detrimental to latent prints deposited on a surface. For example, rain or snow can dilute or obliterate a friction ridge impression.

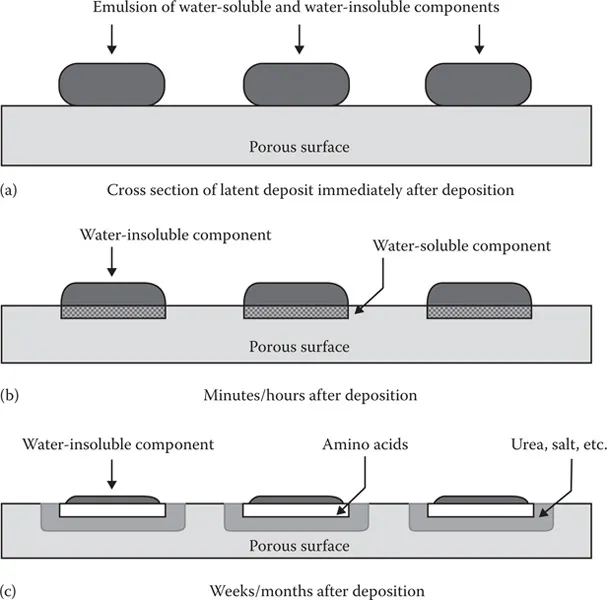

The substrate the print is deposited on also contributes to its durability and the changes in composition that occur over time. Inorganic latent components may produce a chemical reaction with the substrate, such as an oxidation reaction that may cause a fingerprint to become etched onto a metal surface. Porous substrates such as paper, cardboard, or raw wood are absorbent. Just as a sheet of paper will absorb water, so too will a sheet of paper absorb latent print deposits. When the latent print is absorbed into the porous material, the water begins to evaporate, but the residual components remain adhered to the fibrous matrix of the substrate (Figure 8.1).6

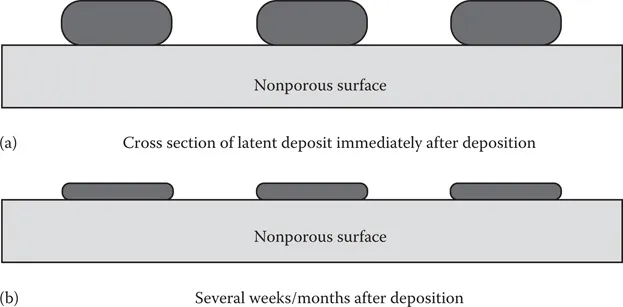

On nonporous substrates such as glass, metal, and plastic, latent prints remain on the surface (Figure 8.2).6 They are therefore exposed to the elements and are more fragile than those on porous substrates. Semiporous items such as magazines, wax-coated paper cups, photographs, glossy paint, or painted/varnished wood have the properties of both porous and nonporous substrates. These substrates absorb the water-soluble deposits, though much more slowly than porous items.5 Water-insoluble components of friction ridge impressions sit on the surface similar to deposits on nonporous substrates.5 Semiporous substrates are processed for latent prints using techniques utilized for both porous items and nonporous items since they have the physical properties of both.

Figure 8.1 A cross section of fingerprint residues deposited on a porous substrate such as paper. When the fingerprint is deposited on the surface (a), the water-soluble components are absorbed into the substrate (b) and the water-insoluble components remain on the surface (c). (Reprinted with permission from Champod, C., Fingerprints and Other Ridge Skin Impressions. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, 2004, (Figure 4.2).)

Figure 8.2 A cross section of fingerprint residues deposited on a nonporous substrate such as glass. When the fingerprint is deposited on the surface (a), both the water soluble and water-insoluble components remain on the surface (b). (Reprinted with permission from Champod, C., Fingerprints and Other Ridge Skin Impressions. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, 2004, (Figure 4.3).)

8.2 Latent Print Development

Latent prints are made visible using a variety of optical, chemical, and physical development procedures. Many of these techniques initially arose from trial and error.3 As science progressed, specializations developed in the form of numerous subdisciplines dedicated to addressing increasingly specific issues with latent fingerprint development. Contributions from these scientific subdisciplines have led to improved methods for developing latent prints. This burgeoning sophistication and increased scientific rigor have both improved existing methods of development and generated novel techniques for latent print development.4

There are a multitude of powders and chemical reagents available for processing latent fingerprints on porous, semiporous, and nonporous surfaces. There are also chemical reagents available for enhancing patent (visible) prints, which may consist of a bloody or oily matrix. The type of processing method chosen will depend on the condition and type of substrate; the composition of the latent fingerprint; your regional location and its unique atmospheric conditions; and the availability of powders, suspensions, and chemical reagents in your laboratory.

Research in fingerprint development is focused on finding chemical reagents that react with the various components of eccrine and sebaceous sweat to develop latent prints and make them visible. The resulting visible fingerprint may appear to be a specific color, or it may be fluorescent and therefore more readily visible with alternate light sources (ALSs) or lasers (Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3 An alternate light source (ALS).

There are many different processing options. Some have proven superior to others, and many historically popular chemical reagents are no longer in common use. Some processing options work well in humid climates, but not in arid climates. Most items of evidence can be processed with multiple chemical reagents as long as those reagents are used in a specific order. See Appendix A for a list of sequential processing methods for various types of evidence.

Fingerprint development techniques are often broken down into physical processing methods and chemical processing methods. Physical processing implies that the scientist physically enhances the fingerprint using various fingerprint powders and brushes. Chemical processing refers to the use of chemical reagents. This text further subdivides fingerprint development techniques into four categories: physical processing methods, chemical processing methods on porous substrates, chemical processing methods on nonporous substrates, and “other” chemical processing methods. “Other” chemical processing methods will address how to develop bloody or greasy fingerprints, fingerprints on firearms, fingerprints on the adhesive side of tape, and other processing methods such as vacuum metal deposition. See Appendix B for a list of formulations for f...