![]()

East Coast Makers

BY THE MID-1960s people in many levels of society were exploring alternatives to the “business as usual, we have done it this way for years, why change now?” approach to life. Consumer activist Ralph Nader’s exposé of General Motors, Unsafe at Any Speed (1965), had shown that what was good for GM was not necessarily good for America. Nader’s citizen action groups lobbied for consumer, financial, and legal rights, and demonstrated that there were alternatives to established customs. At a time when Kodak was promoting its inexpensive, easy-to-load Instamatic color film and drive-thru Fotomat kiosks were the latest way to get one-day machine photo finishing, a cadre of East Coast photographers was cultivating the advantages of making your own emulsions along with benefits of personally controlling the process.

These transformative makers challenged the cherished notions of photographic veracity and time with an emphasis on finding new and often unintended ways to employ contemporary and historic processes and techniques, such as combination printing, Kwik-Print, Kodalith, and multiple images, to contest the assumption that a photograph’s worth should be based on its ability to convey knowledge of visual reality directly from nature. Straining against the established limits, they dared to proclaim that anything one can imagine is real.

![]()

Jerry N. Uelsmann

MFA, INDIANA UNIVERSITY, 1960

MS, INDIANA UNIVERSITY, 1958

BFA, ROCHE STE R INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, 1957

www.uelsmann.net

Jerry N. Uelsmann (b. 1934), known for articulating the concept of postvisualization, received his BFA from RIT (1957), where his teachers Minor White and Ralph Hattersley influenced him. Hattersley believed that “Until the photographer accepts his manipulation of reality for what it really is he will never arrive at full responsibility for his behavior as a photographer.”1 Uelsmann went on to obtain his MFA from Indiana University (1960), where he was inspired by Henry Holmes Smith, who had worked with László Moholy-Nagy, founder of the Chicago School (later Institute) of Design, which merged with the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in 1949.

Uelsmann, who taught at the University of Florida, Gainesville, from 1960 to 1997, outlined and later championed Hattersley’s idea in a paper he delivered in 1966 at a Society for Photographic Education conference in Chicago, in which he urged photographers to consider the darkroom to be “a visual research lab; a place for discovery, observation and mediation … Let us not be afraid to allow for ‘post-visualization.’ By post-visualization I refer to the willingness on the part of the photographer to revisualize the final image at any point in the entire photographic process.”2 Such a statement released photographers from Ansel Adams’s prevailing Zone System, which Adams designed to give photographers repeatable control over their materials so that the final printed outcome could be predicted (previsualized) before the shutter was pushed. Uelsmann also freed photographers from Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Decisive Moment of linking the ultimate moment of creation to the instant of the shutter’s release, since Uelsmann posited that such moments could happen any time during the making process.3

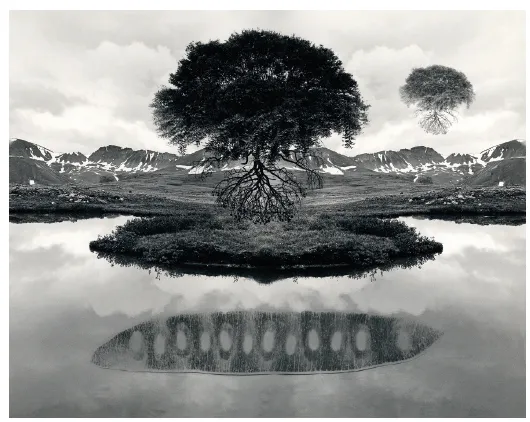

Uelsmann’s practice focused on the darkroom as the place of photographic creation. He and many other photographers of his time responded intensely to the darkroom experience. The dimly glowing light, the sound of trickling water, and the acrid smells of acetic acid and fixer rising from the sink create an otherworldly environment that alters customary space and time, spurring the senses to circumvent the confines of familiarity and predictability. Uelsmann’s darkroom creations revived the nineteenth-century art of combination printing. With consummate skill, he exposed his light-sensitive paper through a series of enlargers, each holding a different negative. The results, which can now be seen as the precursor of the Photoshop era of blending images, disturbed the conventions of the photographic time-space continuum. The work’s innate photographic believability generates a psychological friction that viewers find fascinating. Uelsmann further enhanced the provocativeness of his imagery with poetic titles, such as Small Woods Where I Met Myself (1967), which were the antithesis of Adams’s straightforward ones such as Moon and Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, California (1960).

Uelsmann’s images did not provide the concise message that people had grown to expect from photography through their experiences with mass media, such as Life magazine, in which editorial committees embedded photographs in highly tendentious text that was designed to ensure that the viewers were getting the “right” message. Uelsmann’s sense of the fantastic defied these expectations by opening a private window onto the inward reality of a subject. Manifesting his belief “that the world exists in us as much as it does around us,” Uelsmann’s art fosters an open, dynamic relationship between artist, subject, and viewer. Small Woods Where I Met Myself is a positive-negative basrelief scene where three versions of an indistinct young woman stands among a group of young trees and peers into a black reflective surface in which she sees only two of her own ethereal reflections. This constructed scene can be understood as an interpretation of American society’s growing sense of doubt about everything from abortion, to the Vietnam War, to the possibility of assigning meaning to art or life. The work signals the growing awareness that meaning is unfixed, that it changes according to the interplay between the maker’s intentions and the viewer’s understanding. Where there had once been a sense of assurance, ambiguity now prevailed as new realities were visualized. Uelsmann’s one-person exhibition at MoMA in 1967, curated by John Szarkowski, brought such work and ideas to the attention of the photography community. However, Szarkowski’s support was short-lived, as he later damned Uelsmann with faint praise, stating, “Jerry N. Uelsmann’s fanciful, intricate, and technically brilliant montages have been broadly influential, but not widely followed. His pictures persuaded half the photography students of the sixties that manipulated photographs could be both philosophically acceptable and aesthetically rewarding, but few of those students adopted Uelsmann’s fey, Edwardian surrealism, or his very demanding technical system.”4 As the most visible institutional champion of the modernist Straight Aesthetic espoused by Ansel Adams in such statements as “the greatest aesthetic beauty, the fullest power of expression, the real worth of the medium lies in its pure form rather than its superficial modifications,” Szarkowski’s ultimate dismissal of “manipulation” and hybrid photographic form ran true to course.5 Reflecting on that heady time, Uelsmann reminisced, “We [Duane Michals, Lucas Samaras, and I] were considered part of the crew that challenged the implied limits of the medium ….” In hindsight, Uelsmann is the analog forerunner of digital imaging.

© Jerry Uelsmann. Untitled, 1969. 16 × 20 inches. Gelatin silver print.

Robert Hirsch interviews Jerry N. Uelsmann

What do you do and why do you do it?

I believe you can invent a reality that is personally more meaningful than the one that is literally given to the eye. Nathan Lyons once wrote: “the camera knows more than the eye sees.” I did this parody: “perhaps the mind knows more than the camera sees.” I consider myself a Modernist. When you move from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, you move from outer directed art––art that fulfilled the needs of the society and the patron––towards art that was much more personal and self-expressive. I am from a period when you could identify the unique a...