![]()

1

What This Book Is About

____________________________________

____________________________________

WHAT IS PROGRAM EVALUATION?

Program evaluation is the application of empirical social science research methods to the process of judging the effectiveness of public policies, programs, or projects, as well as their management and implementation, for decision-making purposes. Although this definition appears straightforward, it contains many important points. Let us deconstruct the definition.

What We Evaluate: Policies, Programs, and Management

First, what is the difference between public programs, policies, and projects? For the purposes of this book, policies are the general rules set by governments that frame specific government-authorized programs or projects. Programs and projects implement policy. Programs are ongoing services or activities, while projects are one-time activities that are intended to have ongoing, long-term effects. In most cases, programs and projects, authorized by policies, are directed toward bringing about collectively shared ends. These ends, or goals, include the provision of social and other public services and the implementation of regulations designed to affect the behavior of individuals, businesses, or organizations.

While the examples in this text refer to government entities and public programs or projects, an important and growing use of program evaluation is by private organizations, including for- and not-for-profit institutions. Not-for-profit organizations frequently evaluate programs that they support or directly administer, and these programs may be partly, entirely, or not at all publicly funded. Similarly, for-profit organizations frequently operate and evaluate programs or projects that may (or may not) be funded by the government. Further, many organizations (public, not-for-profit, or for-profit) use program evaluation to assess the effectiveness of their internal management policies or programs. Thus, a more general definition of program evaluation might be the application of empirical social science research methods to the process of judging the effectiveness of organizational policies, programs, or projects, as well as their management and implementation, for decision-making purposes. I chose to focus on program evaluation in a public context because that is the predominant application of the field in the published literature. Private sector applications are less accessible because they are less likely to be published. Nonetheless, the research designs and other methods that this book elaborates are entirely portable from one sector to another.

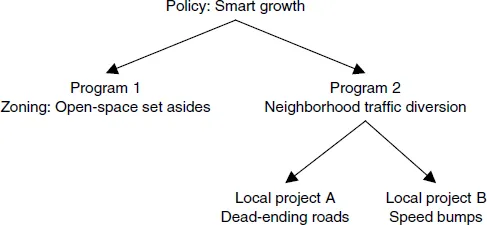

The distinction between policy, program, and project may still not be clear. What looks like a policy to one person may look like a program or project to another. As an example, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) can be regarded at the federal level as either a policy or a program. From the state-level perspective, TANF is a national policy that frames fifty or more different state programs. Further, from the perspective of a local official, TANF is a state policy that frames numerous local programs. Similarly, from the perspective of a banker in Nairobi, structural adjustment is a policy of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The loan, guaranteed by the IMF and serviced by the banker, funds a specific development program or project in Kenya, designed to carry out the market-building goals of structural adjustment policy. But from the perspective of an IMF official in Washington, DC, structural adjustment is just one of the programs that the IMF administers. So, whether one calls a particular government policy initiative or set of related activities a policy or a program (or project) depends on one’s location within a multilevel system of governments. The distinction does not really matter for the purposes of this book. One could call this volume a book about either policy or program or even project evaluation. However, perhaps because the bulk of studies pertain to specific, ongoing, local programs, either in the United States or elsewhere, the common usage of the set of methods discussed in this book is to characterize them as program rather than policy evaluation. We regard projects as short-term programs.1 (See Figure 1.1 for an example of the policy-program-project hierarchy.)

These examples also underscore another point: The methods in this book apply to government-authorized programs, whether they are administered in the United States or in other countries. While data collection may sometimes encounter greater obstacles in developing countries, this text does not focus on specific problems of (or opportunities for) evaluating specific programs in developing countries.2 The logic of the general designs, however, is the same no matter where the research is to be done.

Finally, the logic of program evaluation also applies to the evaluation of program management and implementation. Evaluators study the effectiveness of programs. They also study the effectiveness of different management strategies (e.g., whether decentralized management of a specific program is more effective than centralized management) and evaluate the effectiveness of different implementation strategies. For example, they might compare flexible enforcement of a regulatory policy to rigid enforcement, or they might compare contracting out the delivery of services (say, of prisons or fire protection) to in-house provision of services.

The Importance of Being Empirical

As the first phrase of its definition indicates, program evaluation is an empirical enterprise. “Empirical” means that program evaluation is based on defensible observations. (I explain later what “defensible” means.) Program evaluation is not based on intuition. It is not based on norms or values held by the evaluators. It is based not on what the evaluators would prefer (because of norms or emotions) but on what they can defend observationally. For example, the preponderance of systematic empirical research (that is, research based on defensible observations) shows that gun control policies tend to reduce adult homicide.3 An evaluator can oppose gun control policies, but not on the basis of the empirical claim that gun control policies do not reduce adult homicide. Evidence-based evaluation requires a high tolerance for ambiguity. For example, numerous studies, based on defensible observations show that policies allowing people to legally carry concealed weapons act as if they make it more risky for criminals to use their weapons because, empirically, these policies appear to reduce homicides rather than increase them. Equally defensible studies raise serious questions about the defensibility of that conclusion.4 This example suggests that evaluation results based on defensible observations can sometimes produce ambiguous results. Most people’s intuition is that it is dangerous to carry concealed weapons, but defensible observations appear to produce results that cause us to challenge and question our intuition.

Figure 1.1 The Policy-Program-Project Hierarchy

Although “empirical” refers to reliance on observations, not just any observations will do for program evaluation. Journalists rely on observations, but their observations are selected because of their interest, which may mean that they are atypical (or even typical) cases. Journalists may claim that the case is “atypical” or “typical” but have no systematic way to justify the empirical veracity of either claim. By contrast, program evaluation relies on the methods of science, which means that the data (the observations) are collected and analyzed in a carefully controlled manner. The controls may be experimental or statistical. In fact, the statistical and experimental controls that program evaluators use to collect and analyze their observations (i.e., their data) are the topic of this book. The book explains shows that, while some controls produce results that are more valid (i.e., defensible) than others, no single evaluation study is perfect and 100 percent valid. The book also sets forth the different kinds of validity and the trade-offs among the types of validity. For example, randomized experimental controls may rate highly on internal validity but may rate lower on external validity. The trade-offs among the different types of validity reinforce the claim that no study can be 100 percent valid.

The existence of trade-offs among different types of validity also makes it clear that observational claims about the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of public programs are not likely to be defensible until they are replicated by many studies, none of which is perfect. When many defensible studies, each imperfect in a different way, reach similar conclusions, we are likely to decide that the conclusion is defensible overall. We can act as if the conclusion is true. Note that we do not claim that the conclusion about the program is true, only that we can act as if it were true. Because no method of control can be 100 percent valid, no method of control leads to proof or truth. Mathematicians do proofs to analyze whether claims are true. Because program evaluators do not perform mathematical proofs, the words “prove” and “true” should not be part of their vocabulary.

Lenses for Evaluating Effectiveness

Program evaluation uses controlled observational methods to come to defensible conclusions about the effectiveness of public programs. Choosing the criteria for measuring effectiveness makes program evaluation not purely scientific; that choice is the value or normative part of the program evaluation enterprise. Programs can be evaluated according to many criteria of effectiveness. In fact, each social science subdiscipline has different core values that it uses to evaluate programs. Program evaluation, as a multidisciplinary social science, is less wedded to any single normative value than most of the disciplinary social sciences, but it is important for program evaluators to recognize the connection between a criterion of effectiveness, the corresponding normative values, and the related social science subdiscipline.

For example, the core value in economics is allocative efficiency. According to this criterion, the increment in social (i.e., private plus external) benefits of a program should equal the increment in social (i.e., private plus external) costs of the program. This view leads economists to examine not only the intended effects of a program but also the unintended effects, which often include unanticipated and hidden costs. For example, the intended effect of seat belts and air bags is to save lives. An unintended effect is that, because seat belts and air bags (and driving a sport utility vehicle [SUV]) make drivers feel safer, protected drivers sometimes take more risks, thereby exacerbating the severity of damage to other vehicles in accidents and endangering the lives of pedestrians.5 Thus, program evaluators, particularly those who are concerned with the ability of public programs to improve market efficiency, must estimate the impact of seat belts (or air bags or SUVs) not only on drivers’ lives saved and drivers’ accident cost reductions but on the loss of property or lives of other drivers or pedestrians.

A primary concern of economics that is also relevant to program evaluation is benefit-cost analysis, which ascribes dollar values both to program inputs and program outputs and outcomes, including intended as well as unintended, unanticipated, and hidden consequences. Program evaluation is critical to this exercise. In fact, program evaluation must actually precede the assignment of monetary values to program consequences, whether positive or negative. Specifically, before assigning a dollar value to program consequences, the evaluator must first ascertain that the result is attributable to the program and would not have occurred without it. For example, if program evaluation finds that using cell phones in automobiles had no effect on increasing accidents,6 there would be no reason to place a dollar value on the increased accidents to measure an external ...