![]() Part I

Part I

Introduction![]()

Chapter 1

Motivating observations

Every building is adaptable – but to what end and at what cost? Such seemingly straightforward considerations weigh in any value judgement of whether to adapt or not. The new millennium has seen renewed interest in the adaptability of our built environment, motivated by a number of factors, not least the desire to ‘future proof’ buildings against social, economic and technological change. This attention has spanned planning, architecture, real estate, facilities management and engineering, and a variety of sectors, including housing, offices and healthcare. Leaman et al. (1998) reflects our own experiences, suggesting that adaptability is ‘now commonplace in the vocabulary of briefing, building design and building management’. But the very obviousness of the aspiration, and attractiveness of the flexibility implied, has also resulted in it being frequently sought, but much misunderstood (Carthey et al., 2011). We are also minded of another slippery concept, value – of which Abraham Maslow said ‘My belief is that the concept of value will soon be obsolete. It includes too much, means too many diverse things and has too long a history’ – since we are in some sense investigating the ‘value’ of adaptability (Maslow, 1962).

[T]he problem is temporary thus the solution must be as well.

Hertzberger (2005)

Our aim is to bring some much needed clarity to the subject by providing a more nuanced insight into what constitutes adaptability in our built environment and the factors that give rise to different levels of adaptability in buildings. In doing so, we seek to look beyond what we have termed the ‘black box’ of adaptability – the stereotypical design characteristics, such as generous floor-to-floor heights, movable walls and open plan spaces, that are usually associated with adaptability in buildings. This narrow viewpoint takes account of a limited selection of physical solutions at the expense of not considering the actual user needs and invoking a broader range of tailored solutions. Although such design characteristics are important, they are only a small part of a complex picture; adaptability in our built environment is also contingent upon a wide range of other physical and social factors, which we seek to foreground (Figure 1.1).

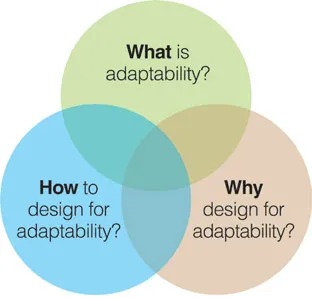

There are three interrelated themes running through this book (Figure 1.2): the first is about meaning – what adaptability means to different stakeholders in disparate contexts and at varying points in time; the second is the factors that lead to different levels of adaptability in the built environment – the reasons why buildings are designed and built to be more or less adaptable; and the third is the characteristics that make buildings more or less adaptable, including the strategies and tactics for how to design and build for adaptability. Ultimately it is difficult to divorce the ‘what’, ‘why’ and ‘how’ of adaptability from each other – the themes inevitably overlap. For instance, one’s notion of what adaptability means will inevitably influence whether or not it is deemed necessary in a particular context and how it could be realised in design terms. But we like to try to keep things simple (at least for now!) by introducing these three basic considerations separately.

Figure 1.1 Looking beyond the ‘black box’ of adaptability

Figure 1.2 The three interrelated themes that underpin this book

Any project that makes a serious attempt to address these three questions is already ahead of the pack.

1.1 Unravelling the ‘what’

As we explore in Part II, the idea of adaptability in buildings is not new and has spanned many centuries and cultures. But this also means that adaptability is a fluid concept. Friedman (2002b) suggests that ‘Misconceptions about adaptability are the outcome of the term’s many definitions and interpretations’ and this was certainly evident in our research in the construction industry. We found that its stakeholders use a diverse range of terminology when talking about adaptability – it meant different things to different people, with instances of shared meaning reflecting conventions, practices and priorities within particular sectors or projects, rather than within professional disciplines. In other words, notions of adaptability tend to be heavily influenced by context, an issue revisited in Part III.

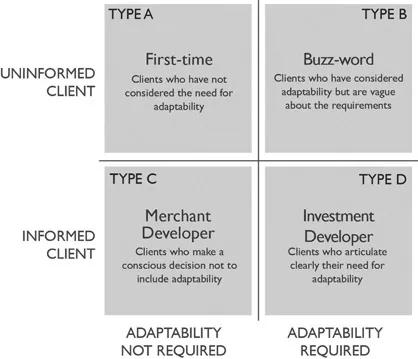

Such differences in terminology are not just a matter of academic interest; developing a clear understanding of what adaptability means in practice is particularly important in the briefing process, when clients communicate their intentions and objectives to designers. Decisions taken during briefing can have costly implications later in the building life cycle – during design, construction and operation – so it is critical that clients and designers speak the same language regarding adaptability. As illustrated in Figure 1.3, some clients do make informed decisions – these are usually experienced or repeat- order clients who have previously managed or procured buildings. However, others are less informed – adaptability is either something that they have not even considered or something that they have thought about but do not really understand (and furthermore may not yet realise this).

Figure 1.3 Types of clients and their understanding of adaptability

One of our objectives in this book is to provide designers and other practitioners with the knowledge and tools to raise clients’ awareness of adaptability and helping to clarify their needs. In the first section of Part III (Chapters 4–7), we explain what adaptability means in practice and the different types that can be implemented in the built environment. The idea being that this will lead to the implementation of more appropriate design solutions – not only recognising opportunities for designing in adaptability but also avoiding unnecessary solutions that increase cost but are rarely implemented. These thinking tools also help keep adaptability on the agenda, reducing the likelihood that adaptability is inadvertently designed out of a building.

1.2 Clarifying the ‘why’

A sustainable building is not one that must last forever, but one that can easily adapt to change.

Graham (2005)

The argument in favour of more adaptable buildings is based on the premise that they will be easier to change in the future, which in turn may give rise to other benefits, such as reducing the costs of adaptation, lessening disruption to building users and making the building easier to let or sell (Table 1.1). Buildings that cannot be adapted cost-effectively may not be fit for purpose and eventually fall out of use or are demolished. Adaptability can therefore be seen as a means to extending the life of our built environment, an important issue at a time when sustainability in buildings has become largely synonymous with the goal of reducing carbon emissions from buildings in use. The notion that the most sustainable building is the one already in existence has grown in currency in recent years and is underpinned by a growing awareness of the energy embodied in buildings during their construction.

Table 1.1 Motives and obstacles to developing adaptable buildings

| Motives | Obstacles |

| Easier to make changes | Perceived additional costs |

| Cheaper to make changes | Short-term business models |

| Easier to sell a building | Lack of price signals |

| Fewer vacancies/rental voids | Valuation practices |

| Less disruption to building users | Discounting of future costs |

| Reduction in material waste | Compromises first use |

| Protect the built asset | Disconnect between funder/beneficiary |

| Good design/planning | Other design considerations are more important |

| Uncertainty about the future | Lack of life cycle costing |

| Long-term ownership | Difficult to prove benefits |

| Previous experiences | No legal obligation |

Adaptability can be viewed as a means to decrease the amount of new construction (reduce), (re)activate underused or vacant building stock (reuse) and enhance disassembly/deconstruction of components (reuse, recycle) – prolonging the useful life of buildings (sustainability).

The case might therefore seem axiomatic – why would you not design for adaptability, given the benefits it can bring? While all of the stakeholders in our study found adaptability to be desirable, it also revealed a number of obstacles (Table 1.1). Cost is usually the main obstacle, the argument being that adaptable solutions cost more than their non-adaptable alternatives. This is an argument that we want to challenge during the course of this book, because not all adaptable design tactics give rise to a cost premium – indeed, in some cases the opposite is the case. However, the focus on initial build costs also overlooks, or discounts, the downstream benefits of adaptability, some of which may manifest themselves in financial terms, while others may be more intangible or unquantifiable (but nonetheless significant). Our tendency to discount future costs and benefits when making intertemporal choices is hard wired into us and inherently undermines our ability to value outcomes in the (more distant) future. This is a significant barrier in that the majority of adaptability’s benefits depend on future conditions. This book can provide you with concepts and tools to make informed decisions and provide a better appreciation of who can benefit from adaptability, when and in what way.

Decisions about adaptability are, at their heart, whole-of-life value judgements.

Other barriers, such as short-term development models, funding practices, an...